In the Freedom Journal series, we look at how freedoms in the political, economic, digital and media landscape have evolved in the last decade.

For five straight years, India has topped the global list of countries on imposing internet bans, with about 60% of all blackouts recorded in the world between 2016 and 2022 having been in India. More than $5.45 billion in economic value was lost due to the bans between 2019 and 2023 alone, according to data from tech company Top 10 VPN.

Freedom in cyberspace hinges on a freely accessible, functional, and affordable internet. The extent of the freedom can be measured based on availability of mobile and broadband services, internet speed, and access to websites and social media platforms. State-imposed shutdowns in the last decade have cited national security and threats to public order when shuttering the internet space. However, rights groups have argued that these shutdowns not only impinge on free speech and human rights, but also violate court directives.

In this article, The Hindu looks at how internet freedom has fared in the last 10 years while the NDA led by the BJP was in power at the Centre.

Internet shutdowns

The government can impose an internet blackout directly (absolute disruption of all internet-based communities) or indirectly, where internet speed is throttled, for a specific population or location. The Indian Government imposed a total of 780 shutdowns between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2023, according to data collected by the Software Freedom Law Centre (SFLC). Instances shot from six in 2014 to 96 in 2023, an increase of 1500%. The highest number of internet shutdowns were implemented in 2018 and 2020. Shutdowns flared up during the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019, the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, and the introduction of Farm Bills in 2021. Internet disruptions in India accounted for more than 70% of the total loss to the global economy in 2020. Data shows India shut down the internet for over 7,000 hours in 2023, affecting almost 5.9 crore people. The disruptions also violated press freedom and people’s right to hold peaceful protests, researchers added.

Indian States and Union Territories can impose an internet shutdown only in case of a “public emergency” or in the interest of “public safety,” according to the Indian Telegraph Act. However, the law does not define what qualifies as an emergency or safety issue. The Supreme Court of India, in the landmark Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India case, reiterated that internet shutdowns violate fundamental rights to freedom of expression, and that shutdowns which last indefinitely are unconstitutional. Moreover, courts have asked governments to make shutdown orders public — a provision poorly complied with, experts have noted in The Hindu.

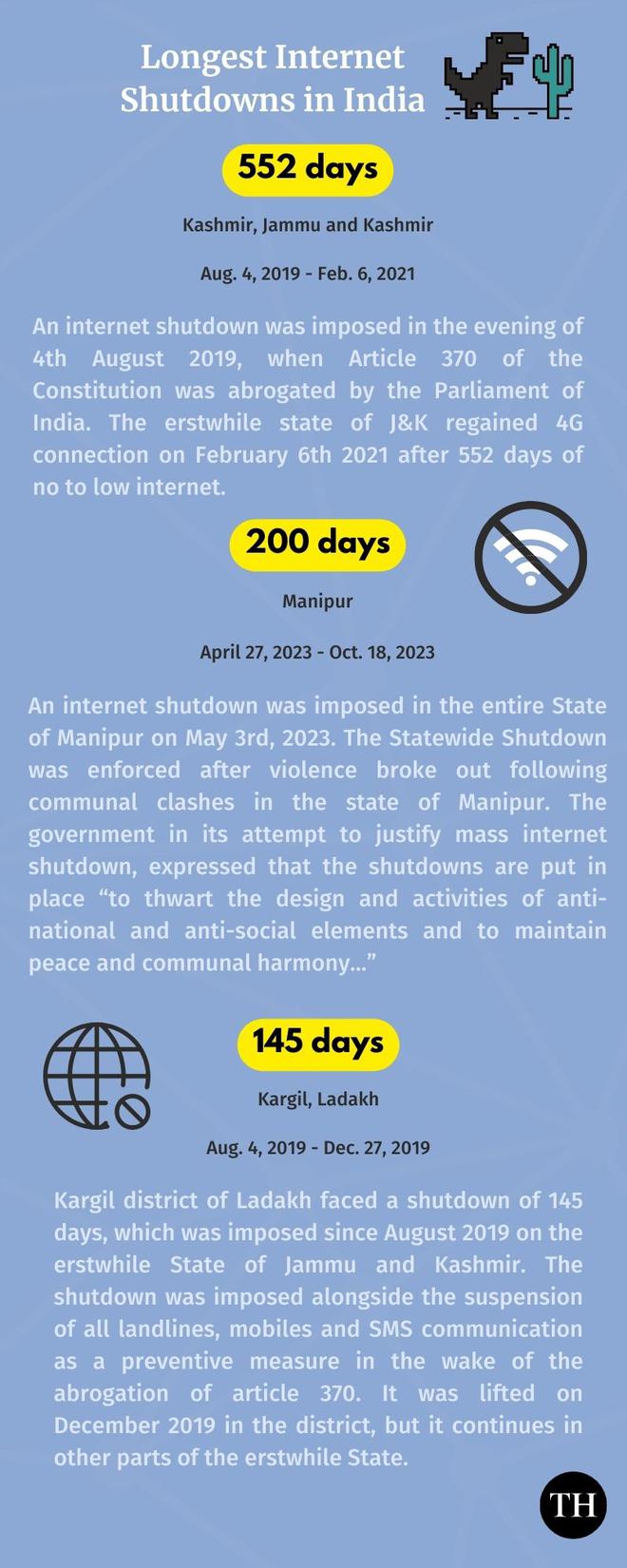

Regionally, Jammu and Kashmir saw the highest number of shutdowns — at 433 — in the last 12 years; followed by Rajasthan, Manipur, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar. The longest blackout in 2023 took place in Manipur from May to December, amid ethnic clashes between the Meitei people, the majority residing in Imphal Valley, and the Kuki-Zo tribal community from the surrounding hills. Preceding this, the longest internet shutdown ever— 552 days— was recorded in Kashmir in 2019-20.

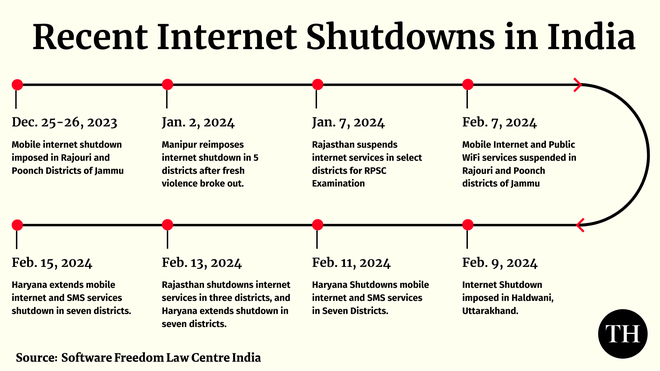

As of February 15, currently active shutdowns are in Haryana, across the districts of Hisar, Kurukshetra, Kaithal, Jind, Sirsa, Ambala and Fatehabad. The Union Government invoked powers under a British-era law to suspend mobile internet, the first time it issued such orders outside the national capital, as Punjab farmers were holding protests in Delhi.

In Jammu and Kashmir, the regions most affected include Pulwama, Anantnag, Srinagar and Shupiyan. Manipur recorded the highest internet ban cases in Churachandpur, Bishnupar and Imphal West. Activists have pointed out that India failed to meet the ‘three-part test’ in imposing blackouts in Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur. Under international law, to block any access to content or invoke coercive measures that violate people’s fundamental rights, countries should check if: the action is provided for by law; pursues a legitimate aim; and follows standards of necessity and proportionality.

The majority of internet outages in the last decade were localised to specific districts, cities and villages. This, however, “translates into an internet blackout for most of the population within this area” as 96% of internet subscribers use their mobile devices to access the internet, noted a Human Rights Watch report. Blackouts deny access to basic rights, and disproportionately impact people from marginalised communities — including MNREGA workers and those who access government subsidies.

The internet was banned in most cases due to political instability, to quell protests and communal violence, and to prevent cheating in exams. For instance, Maharashtra blocked internet services on September 8, 2018, in Pune during the Maratha Quota reservation protests. In 2022, SFLC’s analysis showed out of the 75 shutdowns, 41 were ordered citing “terrorism” as a reason, followed by “communal tension” cases. The trends differ globally: protests are the most common reason for internet shutdowns, followed by information control and political instability.

Most disruptions were imposed preemptively in response to protests. Preventive shutdowns have increased from five in 2014 to 81 in 2023. The highest cases of preventive orders were passed in 2021: including intentional disruptions in Jammu and Kashmir, mobile internet outages during the farmers’ protest, and at least four instances to stop students from cheating on exams.

Websites blocked

Between 2015 and 2022, more than 55,000 websites were blocked, according to SFLC data. The biggest share of content censored was done under section 69A of the IT Act, by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (responsible for 47% of the requests) and the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. URLs were blocked due to links to organisations banned under the UAPA and content that disseminated allegedly fake news (some related to the Indian army and Jammu and Kashmir). Most recently, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology ordered news outlet The Caravan to take down a story which alleged abuse, torture, and murder of civilians by the Indian Army in Jammu’s Poonch district.

On social media, almost 30,000 social media URLs (including accounts and posts) were blocked between 2018 and 2022, with the majority of requests sent to X, formerly called Twitter. “...it is necessary or expedient to do so in the interest of sovereignty and integrity, defence of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for inciting cognizable offence relating to above,” IT minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar said in a written response in the Parliament.

Websites were also blocked additionally for two reasons. Court-ordered takedowns happened for copyright infringement — these account for 46.8% of the total websites blocked. The remaining 1.91% of websites were blocked for promoting ‘obscene’ content, Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM) and pornography.

A commonly cited reason for blocking websites is the escalating threat of cybercrime. As compared to 5,693 cases in 2013, India recorded more than 65,000 cases last year. Cases have risen by almost 434% between 2016 and 2022, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Most were related to fraud, others with the motive of sexual exploitation. The majority of complaints related to financial fraud came from Telangana, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra in 2022. Conviction rates remained below 30% for identity theft, publishing sexually explicit material and cyberstalking, data also showed.

India vs global trends

Global Internet freedom has declined for the 13th consecutive year, and the environment for human rights online has deteriorated in 29 countries, according to the latest Freedom House report. As a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, “there is a certain basic understanding that regulation of the Internet or Internet-based services by governments has to respect basic human rights standards,” Access Now’s Raman Chima told The Hindu in 2020.

India’s ranking has hovered around the same benchmark for the last three years. This is a dip from 2016 and 2017, when India scored 59 points, to 50 points in 2023.