When I read and study Walt Whitman’s poetry, I often imagine what he would’ve done if he had a smartphone and an Instagram account.

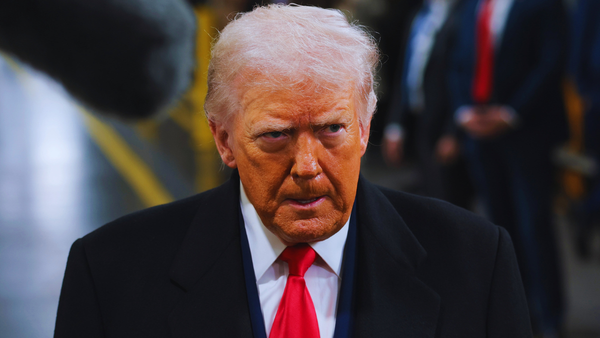

Unlike many of his contemporaries, the poet collected an “abundance of photographs” of himself, as Whitman scholar Ed Folsom points out. And like many people today who snap and post thousands of selfies, Whitman, who lived during the birth of commercial photography, used portraits to craft a version of the self that wasn’t necessarily grounded in reality.

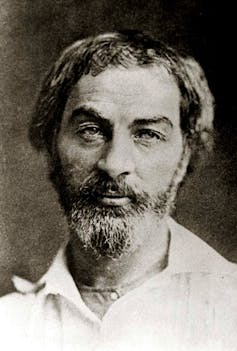

One of those portraits, taken by photographer Curtis Taylor, was commissioned by Whitman in the 1870s.

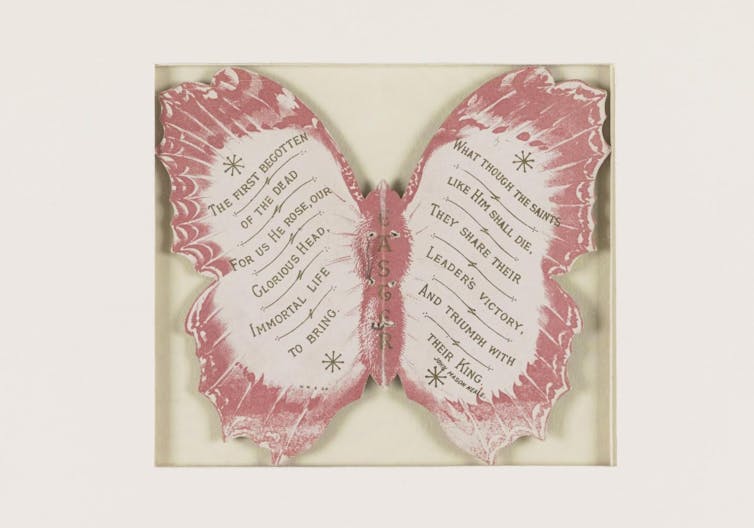

In it, the poet is seated nonchalantly, with a moth or butterfly appearing to have landed on his outstretched finger. According to at least two of his friends, Philadelphia attorney Thomas Donaldson and nurse Elizabeth Keller, this was Whitman’s favorite photograph.

Though he told his friends that the winged insect happened to land on his finger during the shoot, it turned out to be a cardboard prop.

Feigned spontaneity

The scene with the butterfly reflects one of the main themes of Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” his best-known collection of poems: The universe is naturally drawn to the poet.

“To me the converging objects of the world perpetually flow,” he insists in “Song of Myself.”

“I have instant conductors all over me whether I pass or stop,” Whitman adds. “They seize every object and lead it harmlessly through me.”

Whitman told Horace Traubel, the poet’s close friend and earliest biographer, that “[y]es – that was an actual moth, the picture is substantially literal.” Likewise, he told historian William Roscoe Thayer: “I’ve always had the knack of attracting birds and butterflies and other wild critters.”

Of course, historians now know that the butterfly was, in fact, a cutout, which currently resides at the Library of Congress.

So what was Whitman doing? Why would he lie? I can’t get inside his head, but I suspect he wanted to impress his audience, to verify that the protagonist of “Leaves of Grass,” the one with “instant conductors,” was not a fictional creation.

Today’s selfies often give the impression of having been taken on the spot. In reality, many of them are a carefully calculated creative act.

Media scholars James E. Katz and Elizabeth Thomas Crocker have argued that most selfie-takers strive for informality even as they carefully stage the images. In other words, the selfie weds the spontaneous to the intentional.

Whitman does exactly this, presenting a designed photo as if it were a happy accident.

Too much me

As Whitman biographer Justin Kaplan notes, no other writer at the time “was so systematically recorded or so concerned with the strategic uses of his pictures and their projective meanings for himself and the public.”

The poet jumped at the opportunity to have his photo taken. There is, for instance, the famous portrait of the young, carefree poet that was used as the frontispiece for the first edition of “Leaves of Grass.” Or the 1854 photograph of a bearded and unkempt Whitman likely captured by Gabriel Harrison. Or the 1869 image of Whitman smiling lovingly at Peter Doyle, the poet’s intimate friend and probable lover.

Some social scientists have argued that today’s selfies can aid in the search for one’s “authentic self” – figuring out who you are and understanding what makes you tick.

Other researchers have taken a less rosy view of the selfie, warning that snapping too many can be a sign of low self-esteem and can, paradoxically, lead to identity confusion, particularly if they’re taken to seek external validation.

Whitman spent his life searching for what he termed the “Me myself” or the “real Me.” Photography provided him another medium, besides poetry, to carry on this search. But it seems to have ultimately failed him.

Having collected these images, he would then obsessively chew over what they all added up to, ultimately finding that he was far more lost than found in this sea of portraits.

I wonder if – to use today’s parlance – Whitman “scrolled” his way into a crisis of self-identity, overwhelmed by the sheer number of photos he possessed and the various, contradictory selves they represented.

“I meet new Walt Whitmans every day,” he once said. “There are a dozen of me afloat. I don’t know which Walt Whitman I am.”

Trevin Corsiglia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.