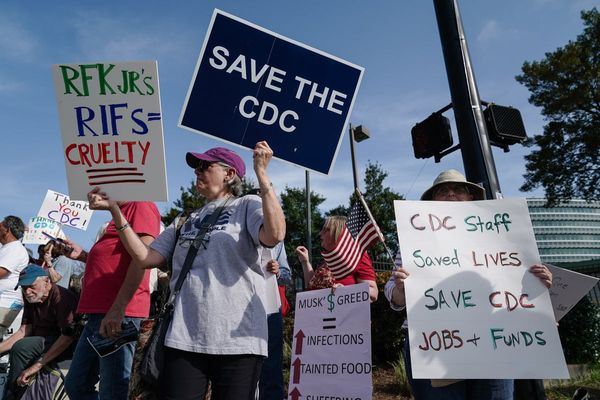

When a senior EU delegation travelled to the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi last Tuesday, they were hoping to discuss ways to limit the increasing numbers of migrants leaving Libya heading north to Europe.

However, shortly after their jet touched down at Benghazi Airport, the cluster of EU foreign ministers – as well as European Commissioner for Migration Magnus Brunner – were sent packing.

There was no agreement, not even a meeting. They were unceremoniously kicked out and declared "personae non gratae," a source on the European side told Euronews at the time, adding that the delegation was caught in a diplomatic “trap” in which Haftar tried to force them to take a photo with, and tacitly legitimise, his Benghazi-based government.

While the EU itself has been remiss to publicly comment on what one senior Libyan analyst said was outright “humiliation,” it is understood that the man they were hoping to strike a deal with was General Khalifa Haftar.

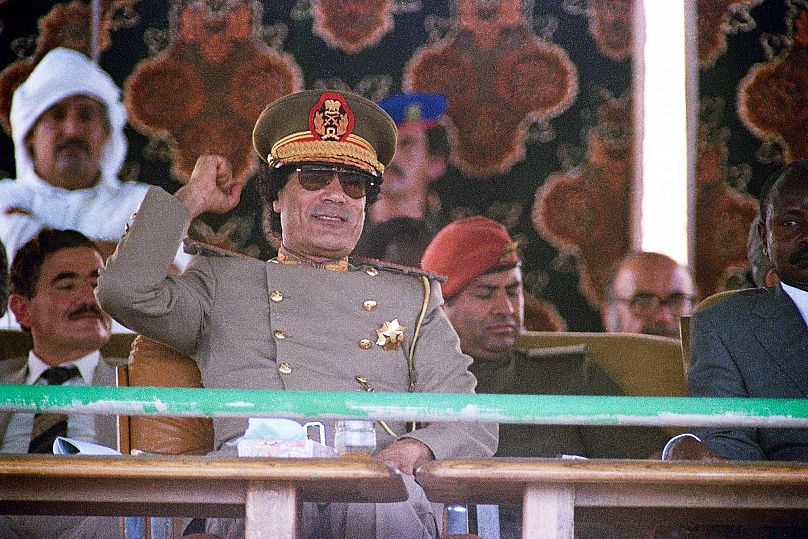

As the head of the powerful Libyan National Army, despite not leading the internationally recognised government, Haftar has become the de facto ruler of vast swathes of the North African country, which has lacked a unified state since the fall and assassination of notorious dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

Although Haftar is arguably the most powerful person in Libya today, he was once persona non grata himself, living quietly in exile right up to Gaddafi’s demise.

Keep your friends close…

Born to an Arab Bedouin family in northeastern Libya at the start of Britain’s eight-year occupation of the country, Khalifa Belqasim Omar Haftar was, even according to his allies, “a very quiet young lad who did not do much work.”

However, he managed to gain admission to the Benghazi Military University Academy, where friends from his time there reportedly also refer to him as “a very stern boy”.

“He would not ask for a fight, but if it came to him, he knew how to handle it,” Haftar's friends described him.

It was at the academy where Haftar got to know a student in the year above — one Muammar Gaddafi.

They became fast friends, with Haftar even labelling Gaddafi an “angel”. The two united over their revolutionary spirit, fomented by a recent political coup that toppled the monarchy and political class in Libya’s neighbour, Egypt.

“We were massively affected by Jamal Abdel Nasser's era and what was going on in Egypt,” Haftar later explained.

Haftar was also said to be a massive admirer of the Iraqi vice president at the time — soon to become another household name.

“Khalifa’s most important son is named Saddam, who by the way is named after Saddam Hussein. He’s the most like his father, I think that tells you all you need to know,” Tim Eaton from the Chatham House Institute said during an interview with Euronews from London.

It is also likely that he chose his title, field marshal, as a nod to Yugoslav socialist leader Josip Broz Tito, experts believe.

Just three years after his graduation, Haftar was instrumental in the 1969 coup, which toppled King Idris and replaced him with Gaddafi, who had expansionist ambitions of spreading his Islamic socialist ideology — also known as Jamahiriya — beyond Libya’s borders.

In subsequent years, Haftar trained in the Soviet Union and rose through the ranks of Gaddafi’s military, commanding the Libyan troops supporting Egyptian troops entering Israeli-occupied Sinai during the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

This cemented what was to become an enduring relationship between the Libyan military commander and leaders in Cairo.

But keep your enemies closer

In 1986, Haftar was made a colonel before becoming the military chief of staff. As the Gaddafi regime became increasingly authoritarian and rogue, his rise seemed inexorable.

However, his luck suddenly turned: Gaddafi's favourite commander led a disastrous mission in the late 1980s into neighbouring Chad, which led to the capture of almost 700 Libyan soldiers, including Haftar himself.

He was jailed, along with his men. Then it was the US, not Libya, that secured his release, which Libyan analyst Anas El Gomati contends was a turning point in the Haftar-Gaddafi relationship.

“Haftar was like Gaddafi’s chosen sword until he became his sharpest blade turned inward,” the founder of Libya’s self-described first think tank told Euronews.

As El Gomati explained, Haftar “was abandoned as a scapegoat, then spent two decades in Virginia plotting revenge."

"He didn’t just oppose Gaddafi, he became his dark mirror, learning every lesson about authoritarian control," El Gomati pointed out.

In fact, Haftar spent the next 24 years in exile and working with Libyan opposition movements, living just kilometres away from Washington, in Langley, the home of the CIA.

In 2019, a former advisor to Haftar in the mid-2010s, Mohamed Bouzier, concurred with El Gomati in an interview with the BBC. “He was inhabited by Gaddafi. He was inhabited by envy of Gaddafi. How Gaddafi ruled this country," Bouzier said.

However, some Libya insiders privately told Euronews of rumours that Gaddafi had actually gifted his former military chief an opulent mansion in Cairo during this time — the same house in which Haftar’s most powerful son, Saddam, grew up.

Back in the fold

When protests erupted across the Arab world in 2011, Libyans took to the streets in cities across the country.

After decades of discussing plots to overthrow Gaddafi with willing Western ears and, as Libya expert Claudia Gazzini describes it, “sort of defecting to the Americans”, Haftar finally saw cracks emerging and soon went to the Libyan capital Tripoli.

However, the International Crisis Group's senior analyst pushed back on the idea that Haftar was a key US puppet in the Libyan revolution.

“I haven't heard anybody make it so explicit. It would make sense, but nobody has said the Americans told him to go back there," Gazzini said.

Even if they did, it would not have been a short-term success, she continued.

“In 2012-2013, he based himself in Tripoli, but he wasn't a big name at the time, because there were just so many different armed groups in Tripoli an the power was balanced out between all these people.”

El Gomati was less diplomatic: “Haftar was a footnote, a Cold War fossil.”

It was not until 2014 that Haftar’s head really appeared above the parapet, when he announced an operation which he said was to root out extremists in Benghazi.

Even then, Gazzini contends that he was not taken seriously. “It was very pathetic. He actually came on TV with a big map behind him saying: ‘Hey, you know, we need to rebel against these bad Islamists.’”

A claim that both Gazzini and Eaton doubt, with the latter telling Euronews that “for Haftar, there’s always been good Islamists and bad Islamists.”

“There’s actually a lot of Salafists (Islamist extremists) in his ranks, just ones who can take orders," Eaton explained.

However, Operation Dignity, as it was known, helped consolidate Haftar’s power over Libya’s second biggest city and much of the country’s east.

Over the following years, he built up his power and became the supreme commander of the Libyan National Army in 2015.

None of this happened in a vacuum.

Family at home, friends abroad

Over the decades, Haftar had built up close relationships in Cairo, but when he returned to Libya, Egypt was also in the midst of revolutionary fervour, tending towards the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood group.

As Gazzini explained, “There was a jihadist threat in Libya and then we have Egypt, which was very weak."

"If you go back to before 2013 before (President Abdel Fattah) El-Sisi, there was this fear that Egypt could implode ... And the Europeans also didn't want Egypt to collapse," she explained.

Faced with difficult choices and fearing the likes of the self-proclaimed IS group spreading their influence in North Africa, some analysts believe that European leaders gave Haftar — whose power and army grew in strength — the silent nod of approval to do what he thinks is right.

"They needed a new Gaddafi, someone who could stop democracy from becoming contagious. Haftar fit the mould: ruthless, ambitious, and willing to trade sovereignty for support," El Gomati believes.

Egypt also backed him as a known known, someone in the immediate neighbourhood who understood the context, but also the perils the region was facing.

The list of backers, silent or otherwise, only continued to grow from there on out. In addition to Cairo, Haftar gained the support of governments ranging from Moscow to Washington, even though the UN did not recognise his wider authority as a legitimate head of state.

However, according to Gazzini, it was Abu Dhabi and Paris who ended up as his most unquestioning supporters. While the Emirates saw the allure of Libya’s oil reserves — the largest in Africa — France and Europe more widely were dealing with an influx of refugees through the Mediterranean, hundreds of thousands of whom were hoping to reach the continent via Libya.

In all that, Haftar saw his chance to utilise the international support and finally become the ruler of Libya — and who knows, maybe even bigger than Gaddafi himself.

When Haftar announced his intention to overthrow the Tripoli-based, internationally recognised Government of National Accord on the day UN Secretary General António Guterres arrived in the capital in 2019, even Egypt warned him against it.

“But he was full of hubris from the Emiratis who wanted to do it. They were giving him aerial cover. The French also wanted to do it,” Gazzini told Euronews from the IRG offices in Rome.

It is a hubris that some have compared to his ally Russian President Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Yet similarly, Haftar’s attempts also failed. Tripoli refused to fall into Haftar’s troops' hands, and Libya fell back into a form of stalemate.

Divided we stand

Throughout this time, Haftar was accumulating extraordinary wealth for his family, whom he had installed in various positions, experts say.

As Eaton told Euronews, “There was a debate on whether when Khalifa (Haftar) died, could his sons come in and take over. It seems that they have come in and started creating their own portfolios even before.”

And it is all in the family and the hands of his children, as El Gomati succinctly outlined.

“Saddam runs the ground forces. Khaled commands the personal guard. Belkacem controls the billions in Libya’s reconstruction fund. Sedig runs the reconciliation file,” he explained. The family has amassed a portfolio estimated to be worth billions.

Despite his failure to seize the wider country, Haftar and his sons continue to run much of Libya.

“He controls everything that matters in eastern Libya,” El Gomati said.

“Oil fields, ports, airports, military bases, and the central bank’s printing press. He has his own air force, controls cross-border smuggling routes… It operates like a state within a state.”

Euronews has reached out to Khalifa and Saddam Haftar for comment.

As shown by the EU's lack of retribution over the past week, the self-proclaimed field marshal also maintains significant international backing.

He was recently in Russia for talks with Putin – a trip he was rumoured to have died on, but once again, he miraculously recovered.

The “humiliation” of the EU delegation also isn’t the first time Haftar has managed to push around supposed allies in Europe.

The analysts Euronews spoke to put this down to Europe’s domestic wranglings over “irregular migrations,” and the simple fact that “there’s no way migrant boats would be leaving the east without Haftar knowing.”

Gazzini gave the example of her native Italy: “At some point, a lot of migrants were going to the coast of Italy about a year and a half ago, he let it be known that he wanted an official visit and an official invitation to Rome. And he got that.”

At the end of his interview, El Gomati did not mince words about the European approach to the Libyan commander. “Europeans keep volunteering as victims. Haftar treats EU diplomats like desperate suitors because that’s exactly what they are.”

It is a point that Eaton also touches upon, albeit somewhat more diplomatically. “There’s a real imbalance,” he concluded.

However, Europe is not acting in a vacuum either. It is often trying to play by international rules and conventions in an arena where shady actions speak much louder than words and agreements on paper.

Sometimes, it is better to have a strongman on your side — or at least his ear.

“We have very little leverage compared to other states. Compare it with the Russians, who have MiGs and have fighter jets that are at Haftar's disposal," Gazzini admitted.

“Compare us to the Emiratis who bring in reinforcements and ammunition in violation of the embargo.”