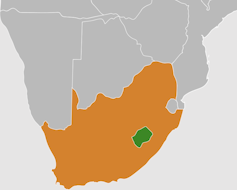

Last year Lesotho celebrated 200 years since the founding of the nation by Moeshoeshoe I. This year the small country in southern Africa will be celebrating the 60th anniversary of its independence from colonial Britain. As it does so, the number of Basotho people who personally saw colonialism end is rapidly diminishing.

Even smaller is the number of people who can claim to have built the institutions that mark post-colonial Lesotho, and post-colonial Africa more broadly. Professor Lehlohonolo Burns Banda Jiane Machobane, who died on 9 August 2025, was one such person.

LBBJ “Burns” Machobane was multi-talented, both as a thinker and as a doer. He taught. He helped build the National University of Lesotho (NUL) into a formidable academic institution that served the region.

He wrote vital books on the systems of governance in colonial Lesotho. He served as the education minister at a tumultuous period in Lesotho’s history and used the position to fight for teachers’ rights.

He didn’t just work for himself, but to benefit those coming after him, a necessity instilled in him from an early age. He epitomised the opportunities that independence symbolised in the minds of Africans in the later 20th century.

As historians we have researched and written extensively on Lesotho’s independence history and post-colonial politics. We have all also benefited from the sage counsel of Prof Machobane, as have generations of scholars and students in Lesotho and far beyond its borders.

His life journey is worth recounting in detail for the unique influences that shaped his intellectual inquisitiveness. His story highlights how Africans in the post-independence period have shaped institutions in important ways, often without getting enough credit for their work.

Early life

Machobane was born in the village of Morija on 24 October 1941. Under colonial rule since Moshoeshoe requested British protection in 1868, colonial Basutoland was governed as a labour reserve. British authorities invested very little in roads, schools, or any economic development as they planned to turn the territory’s administration over to South Africa.

The Basotho had other plans. They created schools, often with the help of missionary churches, and they created political organisations to resist. Morija was an important hub of this activity.

It was the centre of the Paris Evangelical Mission Society, a church that would hand over local control to the Basotho in 1964. The Morija Training Institute, founded in 1868, was the first secondary institution in the country. Morija housed one of the oldest printing presses in southern Africa to print in African languages. It was home to the Sesotho (Sotho language) newspaper Leselinyana la Lesotho, published from 1863.

Machobane was the firstborn of seven children of James Jacob Machobane and ‘Malehlohonolo Rahaba 'Mamotsoahae Machobane.

He received a top-notch education, but it was his father, JJ Machobane, who shaped his worldview. Machobane senior was a politically active novelist and agricultural innovator. He invented a new intercropping method that ensured a steady supply of harvestable food year round.

He called it “Mantsa Tlala” (Stamp Out Hunger). Colonial agricultural officials studied it in the late 1950s, but the elder Machobane promoted the system to better support Basotho women and rural communities. They struggled with the long absences of working-age men who migrated to work in South Africa’s mines. In the 1960s, he opened a school in rural northern Lesotho to teach this system.

Education

In 1960, Machobane obtained a Ford Foundation scholarship to study in the US at the segregated Piney Woods Junior College in Mississippi. At Tuskegee Institute he earned a bachelor’s degree in history and literature, and then a master’s degree in education by 1969.

Machobane started his teaching career at Jackson State University, a historically black institution in Mississippi, in that same year. Coming amid the American civil rights movement, his education was shaped in the crucible of white supremacy, colonialism, and apartheid on two continents.

His stay in the US included earning a second master’s degree, in history, in 1974, beginning his long and distinguished record of academic publication.

Back home

Machobane could have stayed in the US, teaching, but he was called back to Lesotho by a job offer in the Department of Education in 1975. A year later, he took up a post at NUL. Appointed as a history lecturer, he’d found his intellectual home.

At NUL, Machobane was a brilliant teacher and mentor, but also displayed his administrative talents. He was head of department and deputy dean before being appointed pro-vice-chancellor from 1980 to 1982 and acting vice-chancellor from 1986 to 1988. Even so, he continued to teach and write, including finishing a PhD in law at the University of Edinburgh in 1987.

The student population at NUL was growing rapidly in the 1980s. Due to apartheid policies in South Africa, it was one of few institutions in the region where Black students could freely enrol. Machobane helped oversee a golden era at NUL in which many future democratic South African leaders gained degrees, among them former finance minister Tito Mboweni, academic heavyweight Njabulo Ndebele, and former deputy president Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka.

Higher calling

In 1986, the Lesotho Defence Force overthrew then-prime minister Leabua Jonathan, in power since 1965. Civilians were appointed by the military to oversee some key ministries in an attempt to legitimise their rule.

Read more: This award-winning Lesotho film also has social justice at heart

Machobane was tapped as minister of education in 1988. But he was no puppet. He sought to broaden the ways government served the public and led the formation of the Teaching Service Commission. The public body established a pension process for teachers and mandated that schools treat female educators equal to male in terms of pay, working conditions and benefits.

Scholar of the Basotho

Machobane’s work in government and university administration was matched only by his interest in studying the historical evolution of governance. His PhD thesis – Government and Change in Lesotho, 1800-1966: A Study of Institutions – was published in 1990 and remains the gold standard for understanding the roles of colonial and chiefly rule.

He also mentored numerous students and remained an active scholar up to his passing. His passion project, a Sesotho biography of his father, was published in 2024. It was a fitting finale as his father had greatly influenced his life’s work.

It is worth noting that Machobane’s career benefited from the gains his father’s generation had fought so hard to win. The colonial state was giving way just as the younger Machobane came of age. He seized the new opportunities that education, professionalisation and institutionalisation offered. He lived out the promises of independence.

But LBBJ Machobane always stuck his foot in the door to ensure it opened wider and further for those coming behind him. He was rightfully proud of his role in increasing opportunities for Basotho people.

He saved his sharpest words for those who would selfishly limit opportunities through corruption and patronage. He worked tirelessly to make Lesotho’s institutions inclusive.

A lion of the first post-independence generation, Machobane’s life is a cause for reflection across southern Africa today. May he rest in power.

Sibusiso Nkomo (University of Cambridge) and Patrick Y. Whang (University of Cape Town) contributed to this article.

John Aerni-Flessner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.