When you work for Margaret Thatcher, you are either incredibly disciplined and hardworking, or you go home,” says Jeffrey Archer, embarking on a story about the night he was with the then prime minister in Plymouth, where she spoke to the Tory faithful before flying back to London. “As we were walking towards the helicopter, she said, ‘I’m not satisfied with the speech tonight, Jeffrey.’” He assured her that it was exactly the speech she should be making around the country. “She said, ‘No, I’m not happy with it, Jeffrey. Perhaps we could have breakfast tomorrow morning and talk it through.’ She gets in a helicopter. I’m in Plymouth!” He snorts as he recalls the looming six-hour drive to be there on time. “Come on,” he says. “She knew exactly what she was doing.”

This by way of explanation for the hard work and discipline that has allowed this former deputy chair of the Conservative Party, life peer, amateur sprinter, art collector and bestselling novelist to reach a remarkable milestone. Next week will see the publication of his 30th novel. His third and most famous, Kane & Abel (1979), has sold more copies than The Great Gatsby; his new one, End Game, turns on a Russian-Chinese plot to disrupt the 2012 London Olympics. It’s rooted, he insists, in real events. Archer does know, doesn’t he, that we all saw the Games go triumphantly ahead? He holds a finger in the air. “Freddie Forsyth once told me – the late Freddie, who I loved, a dear friend – he once told me, everybody turned down The Day of the Jackal with exactly the same sentence you just delivered. ‘We know [de Gaulle] didn’t die. I mean, who’s gonna read this story?’ Freddie said 15 people turned him down because of the sentence you just delivered.”

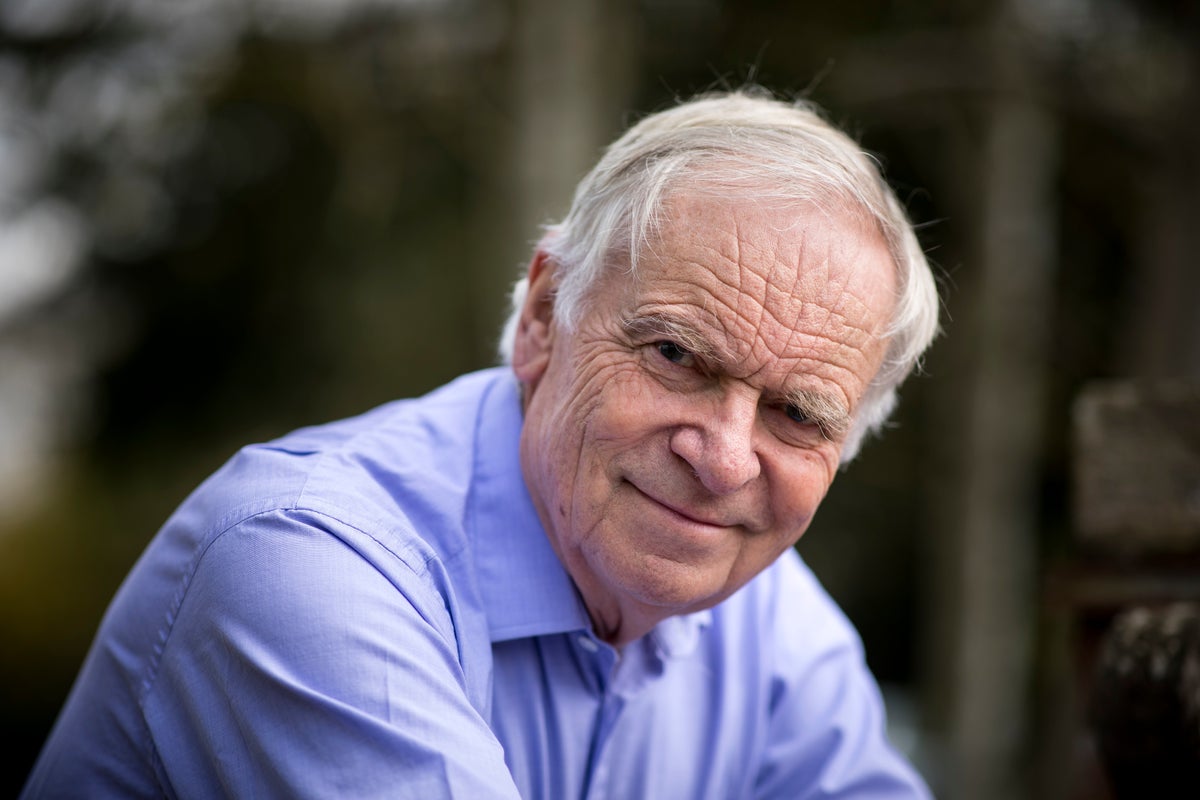

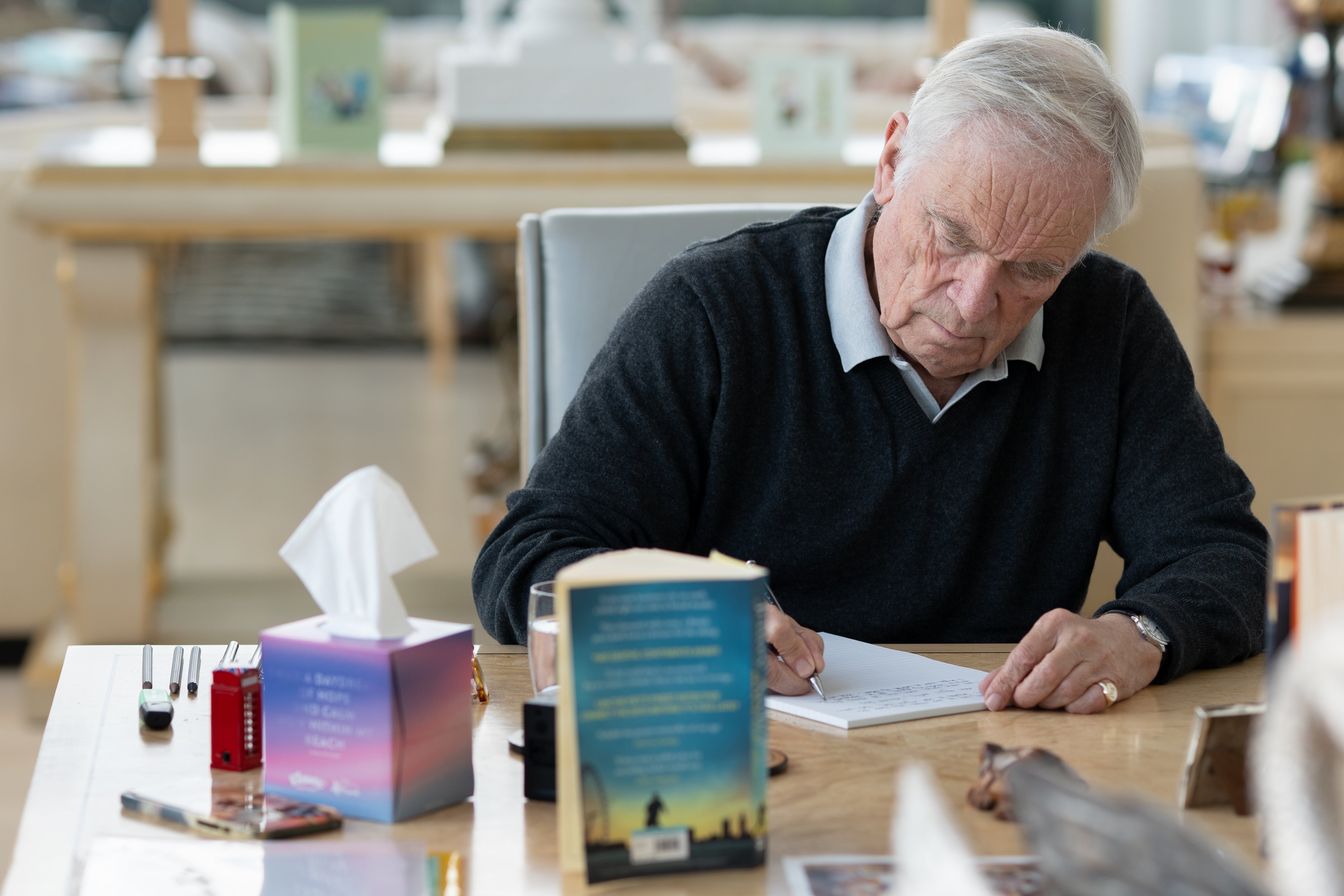

That finger does an awful lot of work for Archer, hitting the beats of a tale like a conductor’s baton, sometimes turning to point at you to stress something more animatedly. Anecdotes and stories flow ceaselessly from him. Each is given drama and dialogue; at least a third of them begin with “Not for printing, but...” He is 85; the grey hair is turning to white, but the smile is as broad as ever. Archer has lost none of his zest. He has charm, too – he couldn’t have reached the political heights without it. Yet his drive is “God-given”, he says. “You can’t pop down to Marks & Spencer and buy a packet of energy. You’ve either got it or you haven’t. I get up every morning at 5.30, work six to eight...” He used to write in blocks, from 6-8am, 10-12pm, 2-4pm, and 6-8pm, beginning in 1976 with Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less – which he wrote after a fraudulent investment firm had wiped out his first fortune, leaving him half a million in debt and facing bankruptcy. “And if you hadn’t been here today, I’d have done 10 to 12,” he adds.

Here is his penthouse apartment overlooking the Thames from the Albert Embankment. It’s a stunner – built in 1964; previously owned by Bond composer John Barry, then by Formula One supremo Bernie Ecclestone, who installed its floor-to-ceiling windows. Through them lies possibly the best view in London: the Houses of Parliament to the east; the great sweep of the river up to Battersea Power Station to the west. The luxurious open-plan interior also comes with serious “room where it happened” vibes. Archer and his wife Mary’s famous shepherd’s pie and champagne soirées attracted the Tory powerful and celebrities, too. The reported directions to the loo – “Turn right at the Picasso and it’s past the Monet” – may be apocryphal, but one could easily get lost en route just taking in his fabulous art collection. Archer sold one Monet, La Seine près de Vétheuil, temps orageux (1878), for £3m at auction in 2011, along with three Warhols, including a striking black-and-white Marilyn, but said in 2018 that he still owns works worth £100m, and his enduring love of art is in evidence all around us.

Most intriguing is the large painting in the hall that he believes to be an earlier version of Rubens’ The Garden of Love, which famously adorned the bedroom wall of Philip IV of Spain. His has a royal stamp on the back, he tells me, and he’s had the wood dated – it came back consistent with the 1633 work in the Prado Museum in Madrid. The telling clue that it was painted by the great Flemish artist, he says, is the visibly corrected nose of the figure in a décolleté dress on the balcony. “When people say to me, ‘Are you worried it’s a fake or a copy?’ I say no, because a copyist or a faker would never have done that.”

An artwork is at the heart of End Game, too: a Van Gogh self-portrait that tempts one of his recurring characters, the wealthy art collector, forger and master criminal Miles Faulkner, into collaborating with the Russians. Archer says that 13 of the book’s 22 incidents that threaten to humiliate Britain on the world stage actually happened. His source: former Met commander Bob Broadhurst, who was head of security for the Games. (The chair of the Games’ organising committee, Seb Coe, he notes, was “useless... flew over to see him in Monaco, we had lunch together, lots of interesting facts but no hampers” – Archer’s word for true stories he can use in his books – “but he put me on to Commander Broadhurst”.)

It’s the final novel in his eight-book William Warwick series, about a detective who rises to the top of the Met. Archer dismisses the idea that his hero is a version of himself, pegging him instead to a hamper-laden former murder squad detective who regularly advises him. Indeed, one might be tempted to see similarities between the master manipulator Faulkner, who has spent time inside, and the author, who was handed a four-year sentence for perjury in 2001.

Archer spent a full two years in jail, producing three volumes from the ordeal, beginning with A Prison Diary: Belmarsh – Hell (2002). The oft-quoted phrase of Mary Archer’s, that her husband has “a gift for inaccurate précis”, pre-dates both the perjury conviction and the 1987 libel trial to which that charge pertained, in which he was awarded a then record half a million pounds in damages from the Daily Star after a front-page story alleged that he had paid a prostitute for sex. The reversal cost him the best part of £2m and his chance to run for mayor of London in 2000, a contest that he might well have won. (It was won instead by Ken Livingstone, the left-wing former leader of the Greater London Council, which Thatcher had abolished in 1986 in a transparent act of political retribution.)

Does he have regrets? “Yes, of course,” he says, “but not many. Not being mayor of London would be one – this is the greatest city on earth. But I’ve been lucky with the books, so I can’t complain. It isn’t as if I then disappeared and became an estate agent.”

His love of politics has never left him. As far back as 2014, Archer was warning that he’d never seen a phenomenon like Nigel Farage, and that the Tories’ biggest mistake would be to underestimate him – that Farage only needed 7 per cent of the vote to stop them from getting into power. Of course, he got double that at the last election and paved the way for a Labour landslide. Now he’s doubled his vote share again, and is polling above 30 per cent.

“He’s the best mob orator I’ve heard in my lifetime,” Archer says, noting that people he knows from all walks of life are thinking of voting Reform. He will not be among them. “I could never vote for him,” he says, emphatically. “Never.”

The Reform leader’s talk of mass deportations and his walked-back boast of stopping the boats within two weeks of taking power may have resonated widely, but Archer isn’t buying it. “He can’t. He knows he can’t. He will do very radical things...”

Archer is not calling for the Tory leader Kemi Badenoch’s head to counter Farage’s demagoguery, though. “I served under two prime ministers in 17 years, and I took for granted that was the norm. My party now wants to change its leader every single year.” When he met Badenoch, he says, he told her that Thatcher’s first year “wasn’t exactly glorious. The voice was wrong, the look was wrong, the attitude, everything.” The big difference, he says, was that the day after Thatcher defeated her opponents in the 1975 leadership contest, “they supported her 100 per cent and didn’t go around plotting to get rid of her”. (They did in the end, of course – she was “killed by her enemies”, as he puts it – but that was much later.)

‘Angela Rayner will be back, and I wouldn’t be shocked if she became Labour leader’

As a Conservative, Archer was a left-of-centre wet – “Margaret thought I wasn’t wet, I was soaking,” he says with a grin. Thatcher admired him, though, and the feeling was mutual, even if some of his views might today lose him the Labour whip under Keir Starmer. His thoughts on the arrests of people protesting against what is happening in Gaza, for instance. “Do I approve of what [Israel] is doing? Certainly not. Do I believe in two states? Yes, I do. And have I sympathy with people who are protesting? Yes, I do. I do have sympathy.

“How can you automatically say every Palestinian is an evil person? How can you look at an eight, nine, 10-year-old child and say, ‘You deserve to be killed.’” He says with “absolutely no antisemitism at all” that he is “anti-Netanyahu, and I suspect I represent a lot of people”.

No stranger to political scandal, he has thoughts, too, on Angela Rayner’s resignation from her deputy leader role over stamp-duty irregularities. “Well, obviously I followed it with great interest,” he says. “Tricky that she was housing minister. I couldn’t have written that, or I couldn’t have got away with it. If you want another prediction, I think she’ll be back a year today, and I wouldn’t be completely shocked if she was leader of the party before the next election. She’s a remarkably able woman. Don’t underestimate her. She’s not dead, she’s alive. Though I’d be fearful of her as prime minister, because I believe she’s every bit as left as Corbyn.”

That scandal was swiftly followed by another. When I ring him later to chat about Peter Mandelson’s sacking as ambassador to the US, he questions how much Mandelson must have known about Jeffrey Epstein, suggesting that information about our closest friends rarely comes as a shock. Mandelson told the BBC: “I relied on assurances of his innocence that turned out later to be horrendously false.”

Archer and Mandelson were pitted against each other when John Major was fighting for re-election (and lost) against Tony Blair. “He’s a formidable opponent. I’ve met him several times.” So was it a mistake to employ Mandelson in the first place? “Well you can always say that afterwards, clever old you, déjà vu, take a mark, Chris.”

Starmer’s decision to restock his cabinet with loyalists, though, is clearly an error, he believes. Thatcher, he says, “only chose the most able people to serve their country. I praise her for picking people like Douglas Hurd, Willie Whitelaw, Nigel Lawson, who could never be described as friends.”

Does Mandelson’s sacking pile pressure on another well-known Epstein associate, Donald Trump? “There’s a lot still to come out,” he says, “and the press aren’t going to let it go that easily. This is a long-running story.” Does he see what’s happening under Trump in the US as the rise of authoritarianism? “Oh yeah,” he says unhesitatingly, invoking the way that the president has been sending national guard troops into Democrat-run cities.

He’s deeply concerned about the way the world is moving. “I’m in that lucky arc that’s never experienced a world war. When I look at Ukraine, I think that could be me, that could be my children, that could be us. I worry for the next generation.” He and Mary have two sons and he’s the doting grandfather of five grandchildren, one of whom, he says, “doesn’t have pop stars on her wall, she has chemical formulae”. She gets that from her grandmother, he notes, not him. Mary Archer is a much-garlanded chemist, who specialised in solar energy conversion. “She feels very strongly about it,” he says. “We have solar energy at our home in Majorca, solar energy at our home in Cambridge.” Is it true that his villa in Majorca is called Writer’s Block? “Yes.” Has he ever had writer’s block? “No. Never never never.”

I ask how he feels about getting older. “Hate it,” he says. “Well, at one level. If someone said, would you like to be 50 again, it would mean having to write all the books again. But I don’t like having to bend down to tie up my shoes and finding it difficult. I’m in the gym twice a week; I go for 10,000 paces a day. So I’m trying to stay active. But I can’t complain, because I’ve had a wonderful life.

“And the other thing is death,” he adds, darkly. “You lose a friend every month.”

He has hinted that his next novel, the one he was writing this morning in longhand on the table behind us, may be his last. How would it feel to write that final full stop? “Oh, no, I’m gonna do film scripts, plays and short stories,” he says.

Jeffrey Archer, one can say with certainty, is undiminished.

‘End Game’ by Jeffrey Archer is published on Tuesday 23 September

In a world of Tommy Robinsons, we need more Stephen Grahams

‘Thatcher would have hated me’: Harriet Walter on playing Maggie as a ‘360-degree human’

Could Keir Starmer really be facing a leadership contest?

Ian McEwan: ‘Too much talk about the news at supper rather ruins the fun’

Annie Lennox: ‘I wanted to perform as a woman, not be regarded as a piece of meat’

The flaw with Charlie Sheen’s memoir is the tragedy of his own life