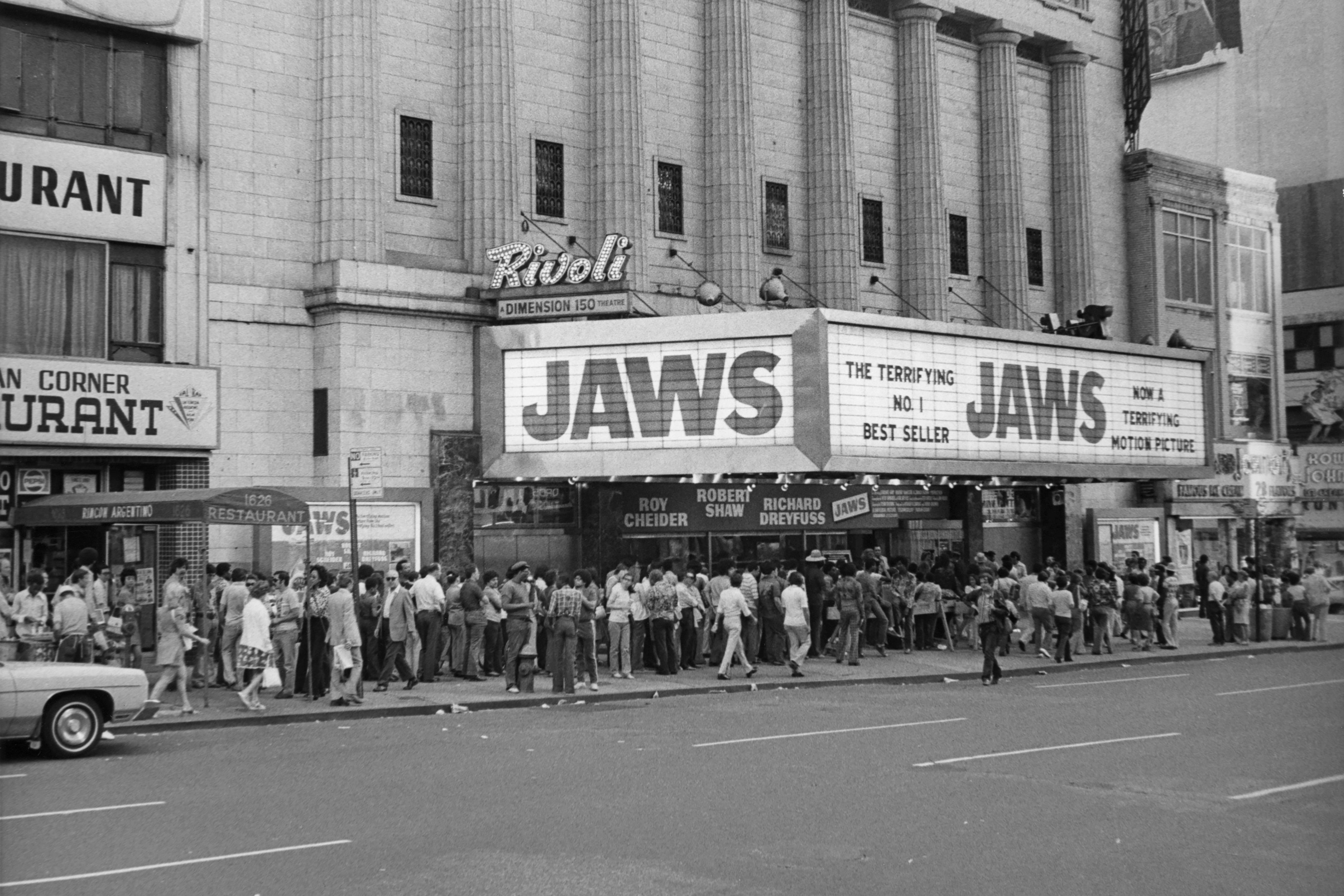

It’s easy to create a villain. Two notes, some clever camera work, and a lingering sense of dread were all it took to hard launch a monster into the ocean, one who tears bodies limb from limb, swallows children and animals whole, and has the capacity to turn seawater crimson within seconds.

Jaws was always about a lot more than sharks. For cinephiles who cite it as one of the greatest pieces of modern cinema, it was about moral corruption, fractured masculinity, and a new frontier in the sheer magnitude of what film could convey. However, as Steven Spielberg’s masterpiece turns 50, for many, its legacy remains inexorably tied to the 25-foot great white at its centre, as illustrated in a new National Geographic documentary tied to the anniversary, Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story. The film features interviews with Spielberg himself and a roster of Hollywood legends, including James Cameron, Jordan Peele, George Lucas, Guillermo del Toro, JJ Abrams, Emily Blunt and Steven Soderbergh, talking about how Jaws shaped their creative lives. There’s also a roster of shark scientists explaining how, despite the initial scares it invoked, Jaws wound up doing more good than harm for sharks. But we’ll get to that.

First, a recap of the plot. Based on Peter Benchley’s bestselling novel of the same name, Jaws tells the story of a deadly shark that viciously rips its way through a fictional US seaside town, Amity Island, and follows the locals’ attempts to find and kill it. But this wasn’t just your average predator. This shark had a human thirst for vengeance, specifically going after those who’d tried to harm it.

To say that the film had a lasting impression on the perception of sharks would be a gross understatement. Following its release in 1975, the number of large sharks along the eastern seaboard of North America fell drastically after thousands of fishers set out to catch trophy sharks in some sort of strange bid to assert their masculinity. Research published in 2021 found that since the 1970s, the populations of the world’s sharks and their close relatives, rays, have declined by more than 70 per cent. Meanwhile, according to a report released at the end of 2024 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, one-third of shark and ray species are threatened with extinction.

Obviously, Jaws is not solely responsible for this – overfishing, the climate crisis and habitat destruction are all partially to blame – but the film plays a significant part in the threat that humans pose to sharks by sheer dint of their perception. And yet, this perception is wildly misguided. Millions of swimmers and surfers go into the seas and oceans every year and yet the average number of shark bites recorded annually is just 64 – and just 9 per cent of those are fatal, according to the International Shark Attack File, the world’s only scientifically documented, comprehensive database of all known shark attacks. That amounts to roughly six humans killed by a shark each year, while humans are estimated to kill up to 100 million sharks in that time, according to the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

“Anybody who was around the water knew to be careful if they were swimming, but Jaws just jumpstarted that fear,” says Wendy Benchley, who, alongside her late husband and Jaws author Peter, dedicated most of her life to shark conservation after the film came out. “We were horrified that people took it as a licence to kill sharks,” she says.

The damage is such that even Spielberg himself has voiced regrets. “I truly and to this day regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film,” he said on an episode of BBC Radio Four’s Desert Island Discs in 2022, adding that he now has his own fears. “Not to get eaten by a shark, but that sharks are somehow mad at me for the feeding frenzy of crazy sports fishermen that happened after 1975.” Benchley, who passed away in 2006, said similarly in 2000: “What I now know, which wasn't known when I wrote Jaws, is that there is no such thing as a rogue shark that develops a taste for human flesh.” Indeed, sharks generally have no interest in us at all. Only about a dozen of the more than 300 species have been involved in attacks on humans.

“Lack of education and misinformation often leads to bad outcomes,” says Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research at the state’s Museum of Natural History. “In the case of the ‘sharks as man-eater myth’, it has caused many people to fear these animals and miss out on learning about one of the most mysterious and fascinating groups of vertebrates on the planet. Just to put things in context, the origin of sharks predates all mammals, all dinosaurs, and all flowering plants... That alone should give people pause.”

Naylor points out that sharks have been around for 400 million years, which is about 200 times as long as humans. While humans have always swum in the sea, and the development of seaside resorts in the Victorian era boosted the pastime, sea-swimming saw its biggest surge in the 1980s, thanks to the widespread popularity of recreational water sports, like snorkelling, surfing and kite surfing. The result? “Humans sharing coastal marine habitats with sharks is a very, very recent thing in the scheme of life on earth,” explains Naylor. “Sharks view human presence in their environment as an anomaly, not a food source.”

That’s not to say there haven’t been gruesome real-life incidents to incite fear. Consider the sinking of the USS Indianapolis in the Second World War. It was July 1945 and the ship, which had delivered parts of the first atomic bomb to the Tinian Naval Base, was sailing towards the Philippines when it was struck by Japanese torpedoes. Within 12 minutes, the 610-foot ship had sunk, leaving around 900 men drifting in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, where hundreds of sharks soon descended. Some fed on dead bodies, others targeted the living.

“We were losing three or four each night and day,” said Loel Dean Cox, who was 19 at the time, in an interview with the BBC. “You were constantly in fear because you'd see ’em all the time. Every few minutes, you’d see their fins – a dozen to two dozen fins in the water.” Despite common misconceptions about the sinking, though, sharks weren’t the predominant reason people died. It was mostly dehydration, sun exposure, and days spent without food and water while the men waited to be rescued. Out of a crew of nearly 1,200, just 317 survived. Estimates as to how many of them died from shark attacks range from a dozen to 150.

Sharks view human presence in their environment as an anomaly, not a food source

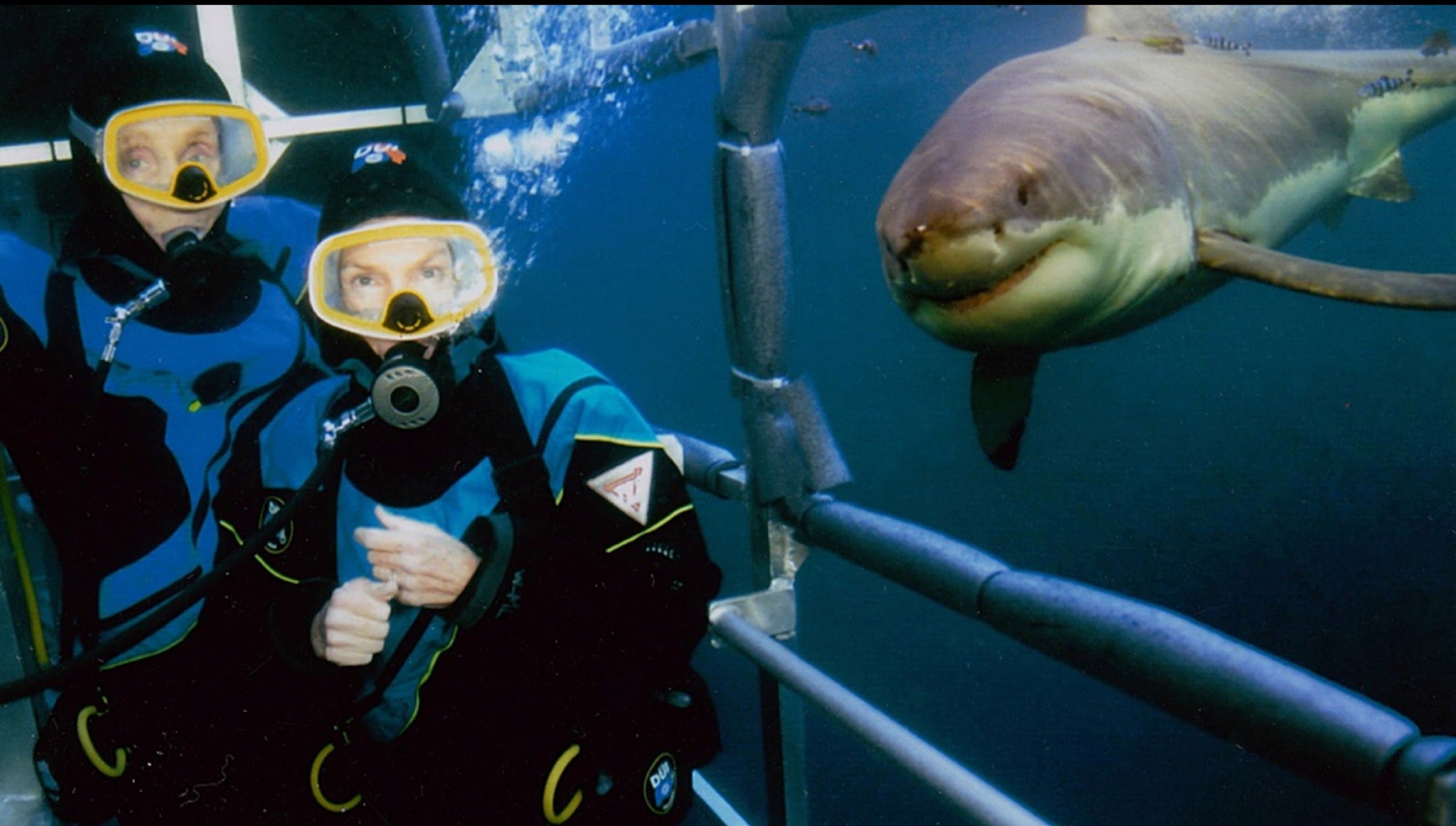

The attack is referenced in Jaws – shark hunter Quint, played by Robert Shaw, tells a harrowing story about his own experience in the water, revealing himself as a survivor. Naturally, his account paints sharks as the primary villains. It’s a direct contrast to Benchley’s own experiences – Wendy tells me that during their filmmaking days, sharks were so wildly uninterested in coming near them in the water that they had to bait them with prey so they’d come close enough to capture on camera.

For their 40th wedding anniversary, the couple went cage diving with female great whites off Guadalupe Island in Mexico. “That was magnificent,” she recalls. “We would have three or four big female great whites just cruising past the cage like grey torpedoes and I could put my hand out and stroke them slightly from head to tail. They don’t wiggle a lot when they swim. That was a thrill. It was an exciting life to be able to do that.”

For Laurent Bouzereau, who directed the National Geographic documentary, Jaws was never really about sharks at all. “I hadn’t thought about the impact the film had on sharks until I made this film,” he confesses. It was only after meeting the Benchley family, all of whom feature in the documentary, and speaking to the litany of shark and ocean experts, that his perception shifted. “One of the reasons Steven wanted to do this film was to talk about this and how it was a completely unintended consequence of the movie. Because in his mind and my mind, you know, the shark is a metaphor. I never looked at it and worried, is this realistic? Could this happen?” The thing that elicited people’s fears, argues Bouzereau, wasn’t the shark itself; it was the fear of the unknown. “And the fear of being vulnerable in the ocean and not knowing what’s underneath,” he adds. “The shark became symbolic of that feeling that we all identify with. So sharks unintentionally became the bad guy.”

The documentary examines how, despite that initial knee-jerk reaction from shark hunters, Jaws had a hugely positive impact on shark conservation long term. “The applications to study marine science shot up after Jaws,” says Wendy. “Peter also received thousands of letters from people saying they wanted to learn more about sharks and be just like Hooper,” she adds, referring to the character played by Richard Dreyfuss, who worked as a marine scientist. “It’s thrilling for me to have this out because not only does it show the magic of Steven’s movie, but it goes into the positive effects of Jaws.”

Some facts to illustrate the incredulity of sharks as a species: they are apex predators and, as a result, are crucial to maintaining the health of marine ecosystems. They can get up to 30,000 teeth in a lifetime, given that they never stop generating them. They can hugely vary in size, with whale sharks stretching to around 12 metres long. And, perhaps most fascinatingly, they have a sixth sense thanks to a specialised sensory organ on their snouts, the ampullae of Lorenzini, that helps them sense electric fields emitted by nearby prey. Tragically, their fins are a delicacy in Asia, which is one of the reasons many are caught and killed.

“There’s a real love for sharks now,” chimes Bouzereau. “You see people saving ones on Instagram that have been beached. Things have changed and people understand that the ocean is their territory. If I go to the jungle, I’m not going to be walking around embracing lions. It’s the same thing with the ocean, so sharks are getting a much better name and I was thrilled to be able to include that angle in the film. I don’t think any other movie has had that kind of U-turn impact.”

As soon as you start reading about sharks, it doesn't take long to realise how much respect these creatures deserve. Majestic, intelligent and largely unthreatening to humans, there’s no better time than now to replace fiction with fact and see them for what they are: fascinating animals we should do everything to protect.

‘Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story’ premieres on Friday 11 July at 8pm on National Geographic and streams the same day on Disney+

Steven Spielberg reveals which film that he thought would end his Hollywood career’

‘I was on the Circle Line when it happened’: 7/7, the day that changed the nation

Such Brave Girls’ Kat Sadler: ‘I don’t care if it makes people uncomfortable’

Abby Elliott on SNL exit: ‘It was the worst that could happen – and then it did’

Time to stop celebrating the Mitford sisters – they are Downton Abbey with swastikas

Heston Blumenthal on his bipolar diagnosis: ‘It’s changed everything’