Once a modest Central Asian security forum, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation now pits Beijing’s ambitions against Western dominance, with its August summit casting President Xi Jinping as a champion of a new multipolar order. But internal rifts raise doubts that it can rival NATO.

From a small-scale security-building mechanism to a heavyweight bloc showcasing China’s geopolitical ambitions, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) has evolved dramatically since its inception in 1996.

Originally known as the Shanghai Five, the group was initially formed of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and aimed to resolve border disputes and bolster security cooperation.

“It was really concerned with China's internal borders with countries like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and looking at things like drug misuse, gun running and political opposition,” explains Michael Dillon of the Lau China Institute at King's College London.

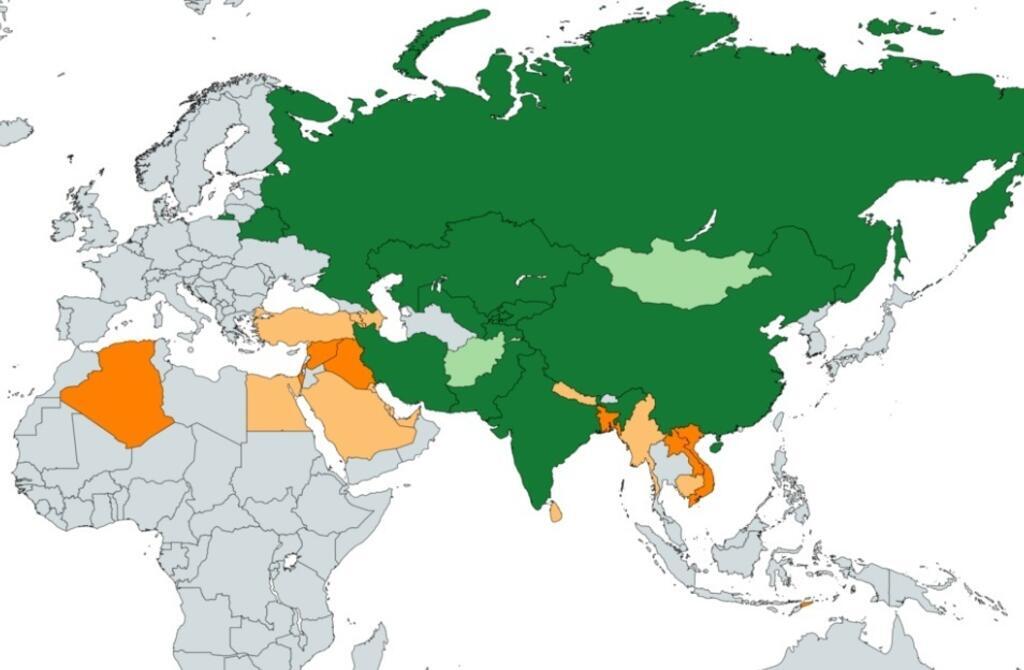

Uzbekistan joined in 2001, prompting the rebranding to SCO, and India and Pakistan later became full members, with Iran the most recent addition, two years ago.

Over time, the SCO’s agenda expanded well beyond border security to include economic cooperation, cultural exchange and coordinating their political message.

The organisation now has 10 member states (with observer states such as Afghanistan and dialogue partners including Turkey), highlighting its growing global footprint.

Last month's much-publicised SCO summit, held in the Chinese port city of Tianjin alongside China’s grand military parade marking 80 years since the end of the Second World War, provided a vivid demonstration of the organisation's expanded role.

President Xi met with almost 30 world leaders – including Russia's Vladimir Putin, India's Narendra Modi and North Korea's Kim Jong-un – projecting the image of a China-led alliance of mainly authoritarian regimes challenging Western influence.

Putin and Modi in China for Shanghai Cooperation summit hosted by Xi

“Xi Jinping is using this to shape perceptions of China and of himself,” Dillon told RFI. The optics of Xi flanked by Putin and Kim symbolised an assertive bloc willing to counterbalance NATO and the US-led liberal international order.

But how far does the SCO truly stand as a counterweight to NATO?

On this, Dillon is cautious. "It's beginning to look like it," he said, but added: "There isn’t any [military coordination], apart from the policing functions across the border with Central Asia ... it doesn’t seem to have any military functions outside of China."

Internal rivalries complicate the picture and prevent the SCO from acting as a fully cohesive bloc, such as the strained relationship between India and Pakistan – both members.

Meanwhile, relations between Europe and the SCO also reveal divisions within the former. While few European Union leaders engage with the organisation, countries such as Turkey and Hungary have shown willingness.

“The EU really does need to respond to China's increasing influence,” says Dillon.

Russia ties strain EU-China relations as Beijing summit concludes early

But Europe faces challenges due to China’s growing economic leverage and the United States' diminished credibility in some quarters. “Trump thinks of himself as the great strong man, but it’s clear to seasoned diplomats in China and elsewhere that Washington is incredibly weak,” said Dillon.

According to him, Trump’s actions have inadvertently contributed to China’s rise within Eurasia’s power vacuum. This environment has allowed Beijing to position the SCO as an alternative framework – even attracting traditionally Western-facing countries such as India and Turkey into the fold.

You can see the basis of a counterweight to NATO emerging.

REMARKS by China specialist Michael Dillon on the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

But the summit also exposed underlying tensions within the bloc. Russia’s invitation to Kim Jong-un to Moscow shortly after the Tianjin meeting showcased Putin’s rivalry with Xi for influence over North Korea. Meanwhile, Modi’s absence from the military parade suggested caution among SCO members in fully endorsing China’s military bravado.

Tanks and missiles roll through Beijing as China commemorates 1945 victory

Western observers remain divided on how seriously to take the SCO – both as symbolic political theatre and as a potentially strategic challenge.

Looking ahead, Dillon is sceptical about the SCO transforming into a formal military alliance akin to NATO anytime soon.

“I haven’t seen anything from China recently to suggest they’re trying to turn the SCO into something more permanent and as a counterweight to NATO,” he says. But he acknowledges that institutionalisation of the SCO is likely to be the next “obvious move” if China continues to consolidate its Eurasian coalition.