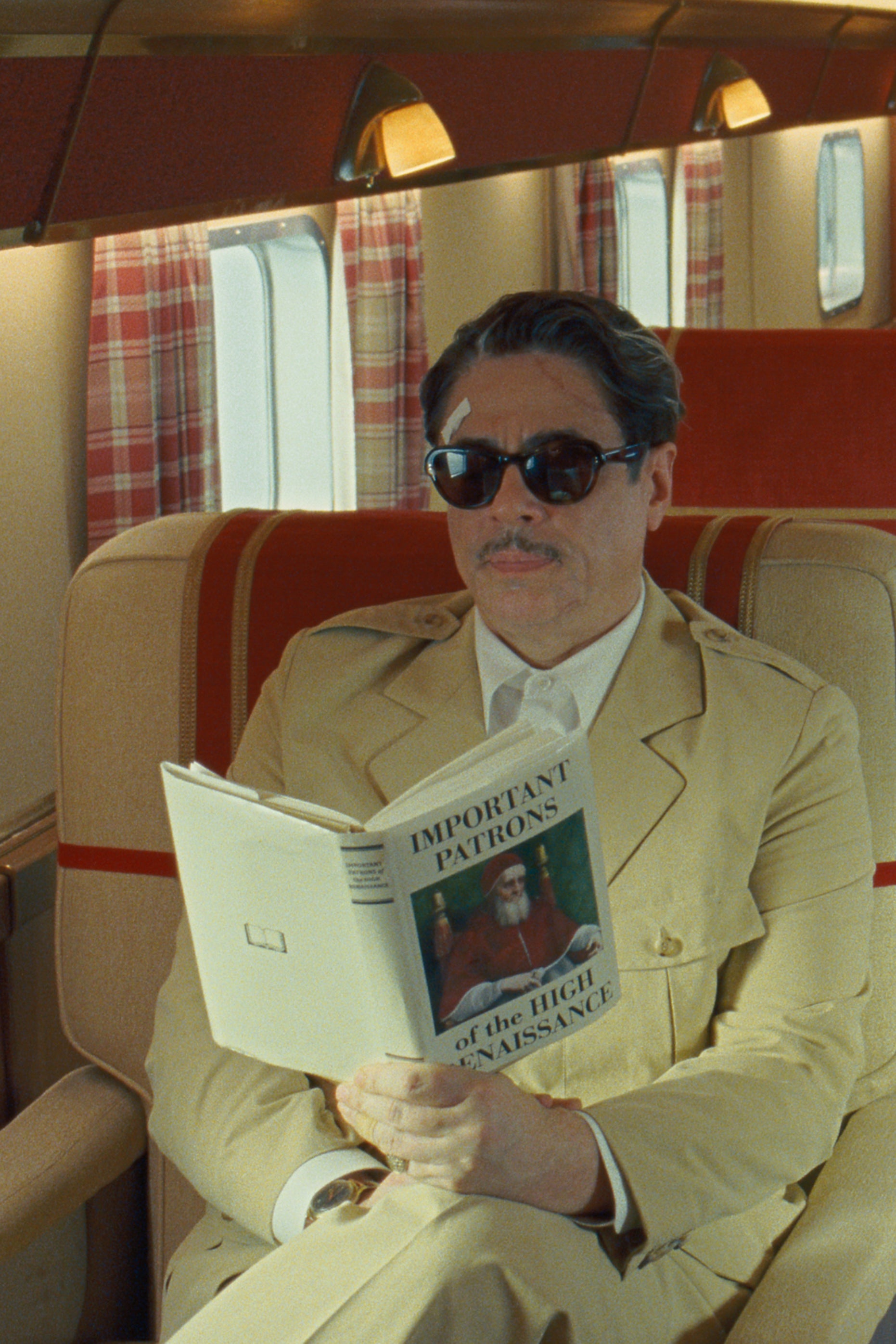

In The Phoenician Scheme, industrialist Zsa-zsa Korda (Benicio del Toro), one of the richest men in Europe, invites his only daughter, nun Liesl (Mia Threapleton), to become his heir on a trial basis. She arranges quarters for herself as humble as can be acquired within the walls of an Italian palazzo-style manor, with its trompe l’oeil marble walls and stacks of paintings by old masters left to gather dust in the hallways.

She sleeps in a cot bed, below an oil work of a young girl sat curled up in the grass. It’s by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. We’re shown the bed two or three times, and only in passing. But, as the film’s set decorator Anna Pinnock assures me, it was supplied with a “thick mattress with real horsehair”, custom-made using traditional techniques, and then fitted with “old linen from French markets that we cut up and remade”.

Welcome to a Wes Anderson set. Here, no detail is insignificant, no corner cut. His worlds are jewellery-box fantasies, with his most recent escapades – The French Dispatch, Asteroid City, and Roald Dahl anthology film The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More – leaning only further into the idea of artifice, of revealing to the audience the artist’s touch. In The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, we see stagehands scuttling about, dragging props and scenery in and out of view. Asteroid City is presented to us as a television show about the staging of a play about an alien visitation. At one point, Bryan Cranston’s narrator turns up in the extraterrestrial story only to stop, ask, “Am I not in this?” and then politely retreat.

The Phoenician Scheme is no different. As Pinnock notes, in the main hall where Korda holds court with both family and business associates alike (no difference between the two, in his mind), there’s a single wooden table on a dais, a raised platform, dressed with “the key elements essential for his business work”.

There’s the odd notepad and pen, a skull to serve as a memento mori, and plans for his most ambitious project yet – an infrastructure scheme in the conflict-blighted, Middle Eastern nation of Modern Greater Independent Phoenicia – organised and divided into a set of small shoeboxes. “But you’ve also got the entry points,” Pinnock adds. “The various doors around the set, which is very much like a stage set, you know? You think of a farce, with people running in and out of doors.”

There’s a wonderful irony to all this. Anderson is famously meticulous, replicating the zebra-adorned, red wallpaper of a now-closed New York Italian eatery for Margot Tenenbaum’s bedroom, or commissioning Marc Jacobs to custom-build a set of monogrammed luggage for the Whitman brothers in The Darjeeling Limited, with the caveat that it must include a dedicated appendage to store a tennis racket. These worlds of his are strange and spirited, several leagues of aesthetic perfection and emotional repression removed from ours. And yet they’re crafted with such comprehensive detail that they feel complete, and utterly convincing in their own way.

This proves especially key to The Phoenician Scheme, where you can sense Anderson – and his frequent collaborator Roman Coppola, co-credited with its story – are trying to work through their rising despair at the state of our own reality. It’s his darkest and most violent film yet, peppered with multiple exploding bodies, gunshot wounds, and poisonings.

And Korda, one of Anderson’s archetypal “bad dads” (think Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum, Bill Murray’s Steve Zissou, and so forth), is his least sympathetic yet. He’s capitalism if it had somehow acquired and learned to puppeteer a human body. He thinks nothing of using slave labour and inducing famines, nothing of the Western opportunists carving up the Middle East for their own gain in the turbulent post-war years. “I don’t live anywhere,” he proudly declares. “I’m not a citizen at all. I don’t need my human rights.”

Everyone’s curious about his childhood, convinced there’s some traumatic incident that might unlock his monstrosity. But the explanation seems simpler than that: he’s defined by the sense of lacking within him, and so spreads out his identity across all the material goods he can acquire. His wealth seems infinite. He has nine sons, several adopted on the off-chance one grows up to be a genius. He’s a voracious reader, always with some book about the history of forgery or pavement engineering in hand. And then there’s all the art. The mountains and mountains of art.

“At the beginning, you know, I was asking, ‘What’s the background of this man?’” Pinnock says. “And we went through all sorts of industrialist collectors, Getty and Hearst and people like that. And then we alighted on [British-Armenian businessman] Calouste Gulbenkian, who was a collector. His collection is in Lisbon now. It’s housed in a museum in Lisbon, but he was a 19th-century collector.” In the minds of these capitalist culture hounds, there’s an idea that hoarding talent means gaining a share in it. “Never buy good pictures. Buy masterpieces,” Korda’s mantra goes.

These pictures, in The Phoenician Scheme, never amount to more than a background detail. Yet, they’re crucial to the understanding of who Korda is and how he operates, and so Anderson did what only Wes Anderson could ever do – acquire genuine masterpieces to cameo in his film. The Renoir above Liesl’s bed is from the private collection of brothers David and Ezra Nahmad. A Magritte is from a collection amassed by Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch. The rest are from Hamburger Kunsthalle, an art museum in Hamburg.

“That came about through someone called Jasper Sharp, who’s a curator and a friend of Wes,” says Pinnock. “He was very helpful in the sourcing and procuring of the real items, which obviously involved its own thread of, you know, the curators, the guards, the conditions to store the paintings in – they had to be stored in another museum local to Babelsburg [Studios, outside of Berlin] overnight. So it was a big operation. But he helped with that, and he also helped me in validating what would stand up and be acceptable as background rented paintings, that were good enough to not be competing with the real thing.”

Pinnock’s first collaboration with Anderson, and with his go-to production designer, Adam Stockhausen, was 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (she and Stockhausen have also worked together on several other non-Andersons, including last year’s Blitz). The Grand Budapest Hotel was what she calls “a strange movie, in a way”. There was an early plan to film it entirely at Babelsberg, with the odd trip out to location – which is, in fact, how The Phoenician Scheme was shot. But Anderson found himself drawn to the small town of Görlitz, on the German-Polish border, a popular filming location already featured in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds and George Clooney’s The Monuments Men. It even housed an ideal space for the hotel itself, an old department store known as the Görlitzer Warenhaus, with five floors built around a large, central atrium.

“So [Anderson] decided to take the whole production on the road,” Pinnock says. “We weren’t any longer in our flats in Berlin. We were suddenly three hours away, down in this little town Görlitz. It changed the strategy, and it changed the daily contact that I would have with Adam, because I had to be in Berlin half the week, sourcing stuff. We did source stuff locally, but it really was coming in from all over, and very often via Berlin. So it was quite the scramble. It sort of serendipitously came together.”

Thankfully, Pinnock and Stockhausen had an unusual guide in Anderson’s assemblage of animatics, storyboards stitched together with sound, here used to pre-visualise nearly 90 per cent of the film. “That’s enormously helpful because the way Wes draws the cartoons, you know the bucket that he has drawn,” she says. “Sometimes he doesn’t want you to merely follow the cartoon. He wants you to bring your ideas, but you certainly have a great anchor. You know from the details in the cartoon that certain specific items are going to be very, very important to him.”

“Sometimes I might show Adam Stockhausen a board of stuff I’ve done, and then we maybe show some elements of that to Wes,” she continues. “Or if it’s something we know he’s fixating on or very keen to be a part of – which is a lot of it – we send him images and communicate that way. And he’s very responsive. He loves to be involved, and it is a real pleasure to work for a director who’s so interested in every detail of everything you do. It’s very gratifying when we get it right. It feels like a proper collaboration.”

The Phoenician Scheme saw Anderson host nightly, communal cast and crew dinners, a now-famous tradition on his sets. “It does make you feel like you’re a part of a repertory company,” Pinnock notes. “It’s very nice.” Indeed, Anderson’s films may be filled with dysfunction, but the ethos behind making them is nothing but harmony.

‘The Phoenician Scheme’ is in cinemas

Wes Anderson isn’t in a rut, but he could do with another flop

Spike Lee says ‘people are hurting’ in jab at Trump’s foreign-made film tariffs

Wes Anderson makes fun of Donald Trump’s ‘fascinating’ film tariff plan

Inside the secret world of Pee-wee Herman – and the man behind him

Matthew Rhys: ‘I’d have played James Bond as a Welshman until they told me to stop’

Cinema’s latest trend? The frustrated descendants of the American western