For centuries prior to modern conservation efforts, indigenous communities cared for the oceans with a fundamentally different philosophy – treating marine environments as family rather than a commodity. With the UN High Seas Treaty set to come into force in January, their knowledge is being formally recognised in the governance of international waters for the first time.

Sixty ratifications pushed the treaty over the line, with Morocco’s kick-starting the 120-day countdown to 17 January.

The treaty offers a tool for nations to create marine protected areas (MPAs) – central to the goal of safeguarding 30 percent of the ocean by 2030.

It also recognises indigenous knowledge, and requires "free, prior and informed consent" – in other words, clear permission in advance – for the use of marine resources linked to that knowledge.

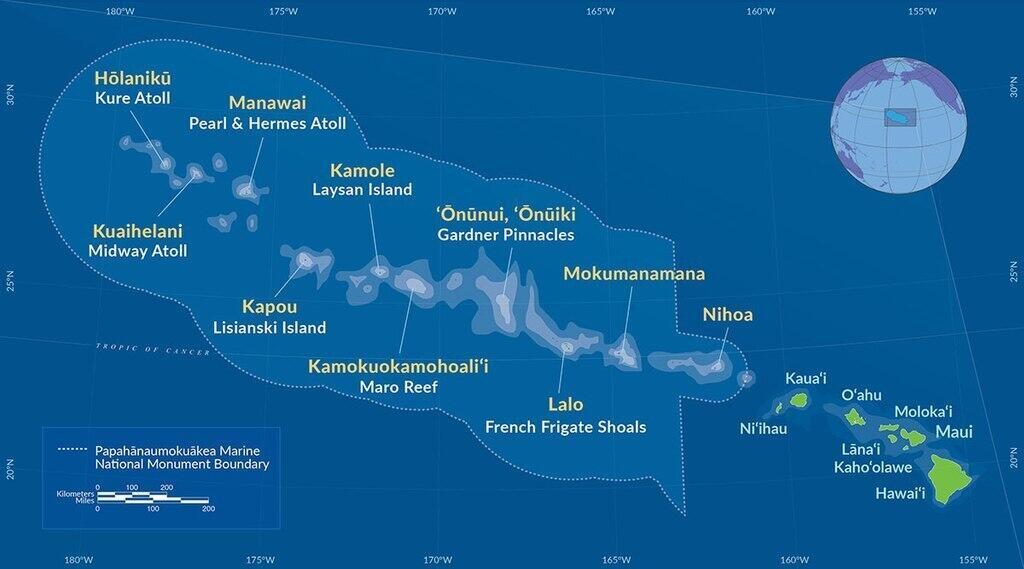

From the sacred waters of Papahanaumokuakea in Hawaii to the hand-built islands of the Solomons, indigenous communities say culture and conservation work hand in hand.

Niue, the tiny island selling the sea to save it from destruction

Culture steers conservation

Stretching northwest from Kauai across roughly 1,500 kilometres of ocean – about the same distance from Paris to Rome – Papahanaumokuakea is one of the world’s largest fully protected MPAs.

It covers around 1.51 million square kilometres, larger than all the national parks in the United States combined, and shelters more than 7,000 marine species, many found nowhere else on earth.

The area is vital for endangered Hawaiian monk seals, green turtles and millions of seabirds.

For native Hawaiians it is also a sacred realm – a place tied to creation stories and ancestral routes at sea.

“I've been involved for more than half my life in protecting a place that we now call Papahanaumokuakea,” Aulani Wilhelm, a native Hawaiian conservationist who played a central role in creating the marine monument, told RFI.

“It was a movement started by native Hawaiian fishermen who partnered with conservationists to protect the coral reefs and endangered species.”

Wilhelm, who also heads the non-profit organisation Nia Tero, said elders had pushed for a refuge rooted in local principles and direct community engagement.

In her words, “not just another model of Western conservation” – but instead protection anchored in values and participation.

Stewardship, not ownership

Papahanaumokuakea is co-managed by four entities: native Hawaiian leaders, the US Federal Government, the state of Hawaii and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Joint decisions cover both nature and culture, and include protecting reefs and endangered species, safeguarding creation stories and traditional navigation routes, and setting rules for access and research.

Instead of talking about “managing” a resource, Wilhelm describes a relationship of care.

“People used to call me the manager of Papahanaumokuakea,” she said. “And I said, I don’t manage anything. You don’t manage your grandmother. You don’t manage your elder cousins. This is a relationship. You ‘care for’ instead.”

The big blue blindspot: why the ocean floor is still an unmapped mystery

From sanctuary to survival

Indigenous people manage around a quarter of the world’s land and many of those places hold rich biodiversity. Advocates say the lesson is simple – when communities have a say, nature often fares better.

In the Solomon Islands the stakes are high. In lagoons such as Langa Langa and Lau, some families still live on artificial islands first built centuries ago. They now face rising seas, chaotic weather and stronger storm surges that push water into their homes.

Lysa Wini, a researcher from the Solomon Islands who works with Nia Tero, told RFI that communities are using what they know and are asking for resources so that guardianship can continue.

“That would be not just merely putting indigenous knowledge or wisdom into text, but actually into practice," she said.

Nations vow to cut shipping noise as sea life struggles to be heard

Next steps

Once the treaty takes effect – and once the first Conference of the Parties (Cop) is held – countries can file formal proposals for MPAs under the new global system. The first Cop must meet within one year of the treaty coming into force.

States will agree basic rules, set up a secretariat, create a science panel and open an information hub to share data. Decisions are taken by consensus where possible, or by a three-quarters majority.

Each proposal must say where the area is, why it should be protected, which measures will apply, how long they will last and how progress will be checked.

Wilhelm told RFI the planet will need 53 more protected areas the size of Papahanaumokuakea in order to meet global targets.