On an afternoon in early July, Immigration Judge Guy Grande appeared on a television on a wall of the courtroom inside Otay Mesa Detention Center in San Diego and called a man from Mexico up to the front to hear his case.

“I held your case over from this morning because you wanted to just take a removal order,” Grande said, a hint of confusion in his voice. “Is that still the case?”

“Yes,” the man responded in Spanish.

According to Grande, the man had entered the United States in August 2023 using CBP One — a phone application created by the Biden administration that asked asylum seekers to wait for lottery-style appointments to come to ports of entry to request protection — and had a pending asylum application in which he claimed a fear of return to Mexico.

Still, he wanted to give up and leave.

The man’s decision was not an isolated case. Crystal Felix, an immigration attorney and the legal representative of the San Diego Immigrant Rights Consortium, said that many are giving up legitimate asylum claims because conditions for immigrants in the U.S. have grown so dire. She said policies including arrests at immigration courts, and the government’s push to keep as many people as possible in immigration custody, make asylum seekers and other immigrants who might qualify to stay feel too hopeless to try.

“There’s just a lot of desperation,” Felix said.

Several people that day in early July asked Grande to deport them. A week later in the same courtroom, Capital & Main saw at least eight more say they also wanted to give up their cases to stay in the U.S. Many had entered using the CBP One app, and at least one was among those recently arrested in immigration court hallways.

According to current and former detainees, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials are pressuring people in its custody to agree to deportation.

ICE did not respond to a request for comment from Capital & Main.

“The officers make people afraid and stressed by telling them that they’ll be in there for a year,” a man who was recently released from Otay Mesa Detention Center said in Spanish.

He noted that conditions inside the facility are enough to make anyone want to give up. He and other immigrants in this article are not being identified due to retaliation concerns.

Detainees at the facility and at others around the country have complained about inadequate medical care, food quality and portions and racism or mistreatment from guards, among other issues. The man said he experienced each of those himself and witnessed firsthand as others endured them while he was inside.

He said conditions were especially rough because the facility is over capacity — he recalled some people having to sleep on mats on the floor because there were not enough beds.

When asked about the conditions at the facility, Ryan Gustin with CoreCivic, the private prison company that owns and operates Otay Mesa Detention Center, said that the company provides “three nutritious meals a day” and “is committed to providing access to high-quality medical and mental health care for all residents.”

Gustin said the facility offers a grievance process for detainees to make complaints and that the company has a human rights policy concerning treatment of people in its custody.

He said every detainee is offered a bed.

The man recently released from Otay Mesa said ICE officers come to units periodically to ask who wants to sign up to leave voluntarily. He said the pressure is particularly strong for those of certain nationalities who can be deported to Mexico because those removals can happen quickly over the land border.

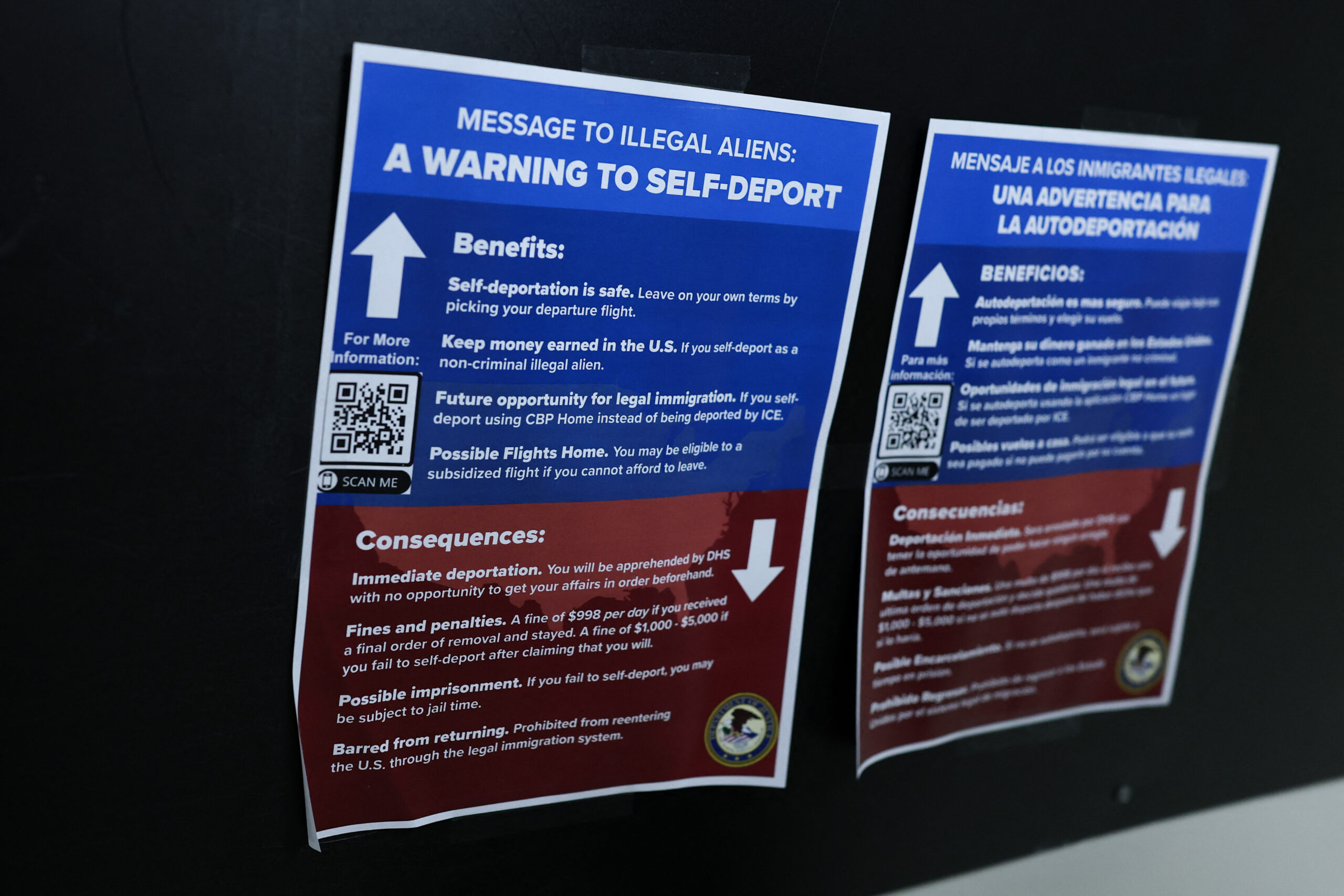

The man said the housing units at the facility have flyers in many languages advertising the Trump administration’s promise to pay people $1,000 if they agree to self-deport. Flyers list the requirements for voluntary departure, the man said, which is a specific program that people who meet certain conditions can request in order to avoid having an official deportation order on their records.

A man detained at Northwest ICE Processing Center in Tacoma, Washington, said his unit has flyers in English and Spanish. He read one over the phone to Capital & Main.

The flyer offers $1,000 and free flights home for each family member who chooses to leave.

“Asking to return home now may give you the opportunity to enter the United States lawfully in the future,” the man said, reading from the flyer. “If you request voluntary departure, you may also qualify to receive a stipend.”

Felix, the immigration attorney, said the flyers mislead people about being able to come back to the U.S.

“That’s giving false hope,” Felix said. “It’s just not transparent.”

In the cases observed by Capital & Main, most of the people requesting to leave asked to sign for voluntary departure, but not all of them qualified.

Among those who ended up with a regular deportation order was the man from Mexico who told Judge Grande that he no longer wanted to pursue his asylum case. Because he had come through the port of entry using CBP One, he could not request a voluntary departure, Grande said.

Grande carefully questioned the man about his decision.

“Are you afraid to return to Mexico or not?” Grande asked.

“To Mexico, no, but to my town, yes,” the man responded. “I’m not going back to my town.”

The man said that he had fled after being threatened by drug cartels.

Grande then asked whether anyone was forcing the man to self-deport.

No, the man said. He wanted to go back to Mexico.

“This is a decision you’re making voluntarily?” Grande asked, putting his question another way.

“Yes,” the man said.

Grande then issued the deportation order. The entire conversation had taken just over 15 minutes.

“I wish you the best of luck in your life,” he told the man.

Felix said people held in ICE custody are facing impossible decisions. She said one client had already spent a year and a half in the U.S., had a pending asylum application with a strong case and was working to send money to his family so they could stay safe while he went through the asylum process when ICE detained him.

“Now he is faced with the impossible situation of staying detained to fight his case or returning to a country where he has already been tortured just to make sure his family is OK,” she said.

In more recent court hearings, Grande appeared to have streamlined his questions. Still, each time he asked the person if they were afraid to go back to their homeland.

One man from Mexico who asked for voluntary departure to Tijuana said he had been in the U.S. since 2009.

“Do you promise you will only return to the United States with legal permission and not try to sneak back into the United States?” Grande asked him.

“Ya no vuelvo,” the man said. I’m not coming back.

As hearings wound down for the day, a Venezuelan woman and man chatted for a moment across the court aisle before CoreCivic guards hushed them.

Both said they wanted to leave, but the woman was worried about being able to get access to her phone before her deportation flight landed in her home country so that she could erase comments critical of the Venezuelan government from her social media accounts.

Despite her concerns that her own government might retaliate against her for her political opinion, she said going there would be better than staying as an immigrant in the U.S.

“It’s only going to get worse here,” the woman said in Spanish.