In our guides to the classics, experts explain key literary works.

Ibn Battuta, was born in Tangier, Morocco, on February 24, 1304. From a statement in his celebrated travel book the Rihla (“legal affairs are my ancestral profession,”) he evidently came from an intellectually distinguished family.

According to the Rihla (travelogue), Ibn Battuta embarked on his travels from Tangier at the age of 22 with the intention of performing the Hajj (the sacred pilgrimage to Mecca) in 1325. Although he returned to Fez (his adopted home-town) around the end of 1349, he continued to visit various regions, including Granada and Sudan, in subsequent years.

Over the course of his almost 30 years of travel, Ibn Battuta covered an astonishing distance of approximately 73,000 miles (117,000 kilometres), visiting a region that today encompasses more than 50 countries. His journeys covered much of the medieval Islamic world and beyond, excluding Northern Europe.

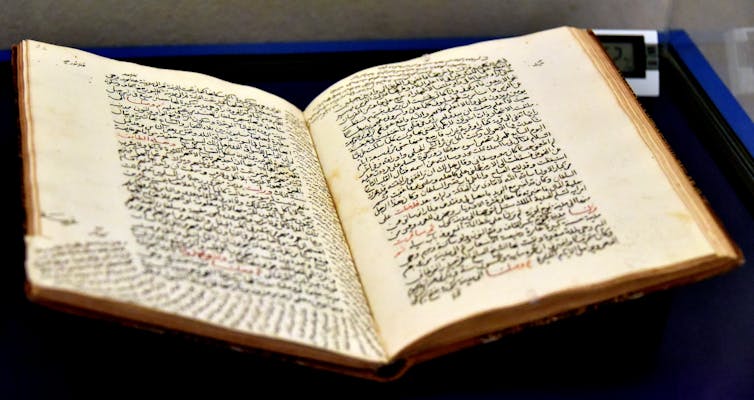

In 1355, he returned to Morocco for the last time and remained there for the rest of his life. Upon his return he dictated his experiences, observations and anecdotes to the Andalusian scholar Ibn Juzayy, with a compilation of his travels completed in 1355 or 1356.

The work, formally titled A Gift to Researchers on the Curiosities of Cities and the Marvels of Journeys, is more commonly referred to as Rihlat Ibn Battuta or simply Rihla.

More than a travelogue or geographical record, this book provides rich insights into 14th-century social and political life, capturing cultural diversity across nations. Ibn Battuta details local lifestyles, linguistic traits, beliefs, clothing, cuisines, holidays, artistic traditions and gender relations, as well as commercial activities and currencies.

His observations also include geographical features such as mountains, rivers and agricultural products. Notably, the work highlights his encounters with over 60 sultans and more than 2,000 prominent figures, making it a valuable historical resource.

The travels

His travels began after a dream. According to Ibn Battuta, one night, while in Fuwwa, a town near Alexandria in Egypt, he dreamed of flying on a massive bird across various lands, landing in a dark, greenish country.

To test the local sheikh’s mystical knowledge, he decided if the sheikh knew of his dream, he was truly extraordinary. The next morning, after leading the dawn prayer, he saw the sheikh bid farewell to visitors. Later, the sheikh astonishingly revealed knowledge of Ibn Battuta’s dream and prophesied his pilgrimage through Yemen, Iraq, Turkey and India.

At the time, the Middle East was under the rule of the Mamluk sultanate, Anatolia was divided among principalities and the Mongol Ilkhanate state controlled Iran, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

Ibn Battuta initially travelled through North Africa, Egypt, Palestine and Syria, completing his first Hajj in 1326.

He then visited Iraq and Iran, returning to Mecca. In 1328, he explored East Africa, reaching Mogadishu, Mombasa, Sudan and Kilwa (modern Tanzania), as well as Yemen, Oman and Anatolia, where he documented cities like Alanya, Konya, Erzurum, Nicaea and Bursa.

His descriptions are vivid. Describing the city of Dimyat, on the bank of the Nile, he says:

Many of the houses have steps leading down to the Nile. Banana trees are especially abundant there, and their fruit is carried to Cairo in boats. Its sheep and goats are allowed to pasture at liberty day and night, and for this reason the saying goes of Dimyat, ‘Its wall is a sweetmeat and its dogs are sheep’. No one who enters the city may afterwards leave it except by the governor’s seal […]

When it comes to Anatolia (in modern-day Turkey), he declares:

This country, known as the Land of Rum, is the most beautiful in the world. While Allah Almighty has distributed beauty to other lands separately, He has gathered them all here. The most beautiful and well-dressed people live in this land, and the most delicious food is prepared here […] From the moment we arrived, our neighbors — both men and women — showed great concern for our wellbeing. Here, women do not shy away from men; when we departed, they bid us farewell as if we were family, expressing their sadness through tears.

A judge and husband

Since Ibn Battuta dictated his work, it’s difficult to assess the extent of the scribe’s influence in recording his narratives. Despite being an educated man, he occasionally narrates like a commoner and sometimes exceeds the bounds of polite language. At times, he provides excessive detail, giving the impression he may be quoting from sources beyond his own observations.

Nevertheless, the Rihla stands out for its engaging style and captivating anecdotes, drawing readers in.

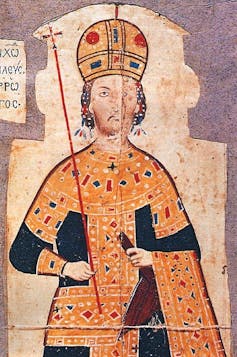

Ibn Battuta later journeyed through Crimea, Central Asia, Khwarezm (a large oasis region in the territories of present-day Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan), Bukhara (a city in Uzbekistan), and the Hindu Kush Mountains. In 1332, he met Byzantine Emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos and travelled to Istanbul with the caravan of Uzbek Khan’s third wife. He mentions a caravan that even has a market:

Whenever the caravan halted, food was cooked in great brass cauldrons, called dasts, and supplied from them to the poorer pilgrims and those who had no provisions. […] This caravan contained also animated bazaars and great supplies of luxuries and all kinds of food and fruit. They used to march during the night and light torches in front of the file of camels and litters, so that you saw the countryside gleaming with light and the darkness turned into radiant day.

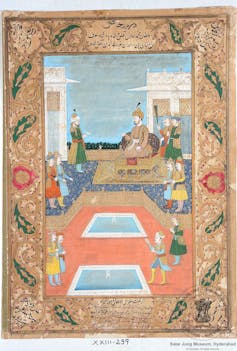

Ibn Battuta arrived in Delhi in 1333, where he served as a judge under Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq for seven years. He married or was married to local women in many of the places he stayed. Among his wives were ordinary people as well as the daughters of the administrative class.

The Sultan’s generosity, intelligence and unconventional ruling style both impressed and surprised Ibn Battuta. However, Muhammad bin Tughluq was known for making excessively harsh and abrupt decisions at times, which led Ibn Battuta to approach him with caution. Nevertheless, with the Sultan’s support, he remained in India for a long time and was eventually chosen as an ambassador to China in 1341.

In 1345 his mission was disrupted when his ship capsized off the coast of Calcutta (then known as Sadqawan) in the Indian Ocean. Though he survived, he lost most of his possessions.

After the incident, he remained in India for a while before continuing his journey by other means. During this period, he travelled through India, Sri Lanka and the Maldives. He served as a judge in the latter for one and a half years. In 1345, he journeyed to China via Bengal, Burma and Sumatra, reaching the city of Guangzhou but limiting his exploration to the southern coast.

He was among the first Arab travellers to record Islam’s spread in the Malay Archipelago, noting interactions between Muslims and Hindu-Buddhist communities. Visiting Java and Sumatra, he praised Sultan Malik al-Zahir of Sumatra as a generous, pious and scholarly ruler and highlighted his rare practice of walking to Friday prayers.

On his return, Ibn Battuta explored regions such as Iran, Iraq, North Africa, Spain and the Kingdom of Mali, documenting the vast Islamic world.

Back in his homeland, Ibn Battuta served as a judge in several locations. He died around 1368-9 while serving as a judge in Morocco and was buried in his birthplace, Tangier.

The status of women

Ibn Battuta’s travels revealed intriguing insights into the status of women across regions. In inner West Africa, he observed matriarchal practices where lineage and inheritance were determined by the mother’s family.

Among Turks, women rode horses like raiders, traded actively and did not veil their faces.

In the Maldives, husbands leaving the region had to abandon their wives. He noted that Muslim women there, including the ruling woman, did not cover their heads. Despite attempting to enforce the hijab as a judge, he failed.

He offers fascinating insights into food cultures. In Siberia, sled dogs were fed before humans. He described 15-day wedding feasts in India.

He tried local produce such as mango in the Indian subcontinent, which he compared to an apple, and sun-dried, sliced fish in Oman.

Religious practices

Ibn Battuta’s accounts of the Hajj (pilgrimage) rituals he performed six times provide a unique perspective. He references a fatwa by Ibn Taymiyyah, prominent Islamic scholar and theologian known for his opposition to theological innovations and critiques of Sufism and philosophy, advising against shortening prayers for those travelling to Medina.

Ibn Battuta’s accounts, particularly regarding the Iranian region, offer important perspectives into religious sects during a period when Iran started shifting from Sunnism to Shiism. He describes societies with diverse demographics, including Persians, Azeris, Kurds, Arabs and Baluchis. His observations on religious practices are especially significant.

Inclined toward Sufism, Ibn Battuta often dressed like a dervish during his travels. He offers a compelling view of Islamic mysticism. He considered regions like Damascus as places of abundance and Anatolia as a land of compassion, interpreting them with a spiritual perspective.

His accounts of Sufi education, dervish lodges, zawiyas (similar to monasteries), and tombs, along with the special invocations of Sufi masters, are important historical records. He also observed and documented unique practices, such as the followers of the Persian Sufi saint Sheikh Qutb al-Din Haydar wearing iron rings on their hands, necks, ears, and even private parts to avoid sexual intercourse.

While Ibn Battuta primarily visited Muslim lands, he also travelled to non-Muslim territories, offering key understandings into different religious cultures, for instance interactions between Crimean Muslims and Christian Armenians in the Golden Horde region.

He also documented churches, icons and monasteries, such as the tomb of the Virgin Mary in Jerusalem. His observation of Muslims openly reciting the call to prayer (adhan) in China is significant.

Other anecdotes include the division of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus into a mosque and Christian church. Most importantly, his encounters with Hindus and Buddhists in the Indian subcontinent and Malay Islands provide rich historical context.

His accounts of death rituals reveal diverse practices. In Sinop (a city in Turkey), 40 days of mourning were declared for a ruler’s mother, while in Iran, a funeral resembled a wedding celebration. He observed similarities in cremation practices between India and China and described a chilling custom in some regions where slaves and concubines were buried alive with the deceased.

Ibn Battuta’s Rihla, widely translated into Eastern and Western languages, has drawn some criticism for containing depictions that sometimes diverge from historical continuity or borrow from other works. Ibn Battuta himself admitted to using earlier travel books as references.

Despite limited recognition in older sources, the Rihla gained prominence in the West in the 19th century. His legacy remains vibrant today. Morocco declared 1996–1997 the “Year of Ibn Battuta,” and established a museum in Tangier to honour him. In Dubai, a mall is named after him.

Notably, Ibn Battuta travelled to more destinations than Marco Polo and shared a broader range of humane anecdotes, showcasing the depth and diversity of his experiences.

Ismail Albayrak does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.