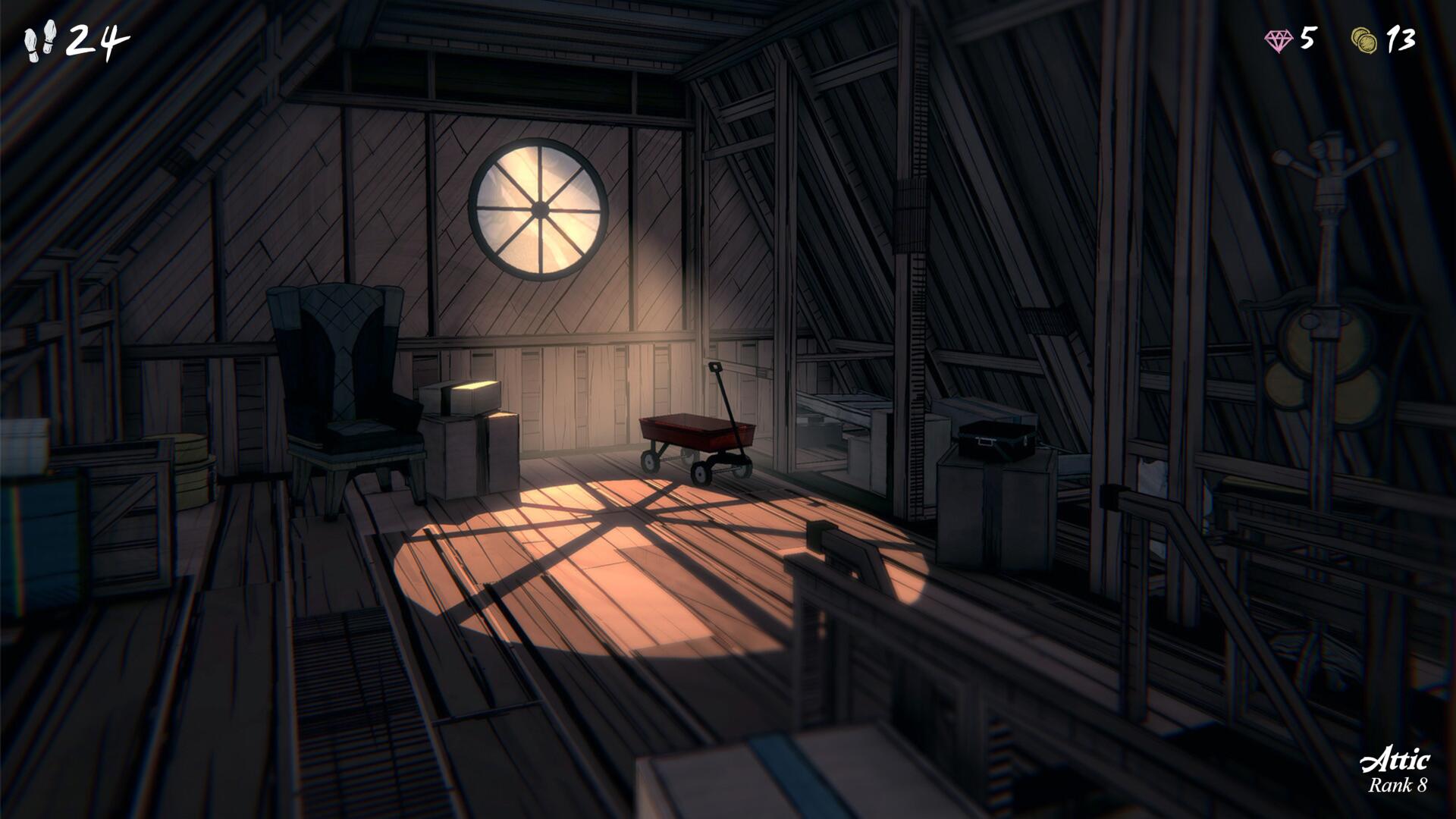

Have you ever had that dream where you see another room in your house? Maybe there’s a little door next to the bathroom, a small hatch next to the stairs, or an attic that doesn’t exist. It’s a theme that my not-quite-nightmare dreams hook onto a lot: the dreams aren’t scary, but there’s a certain horror pallor sticking to them like sweat on bedsheets. Blue Prince is perhaps the game that’s ever come closest to reinvigorating those feelings within me as I play it.

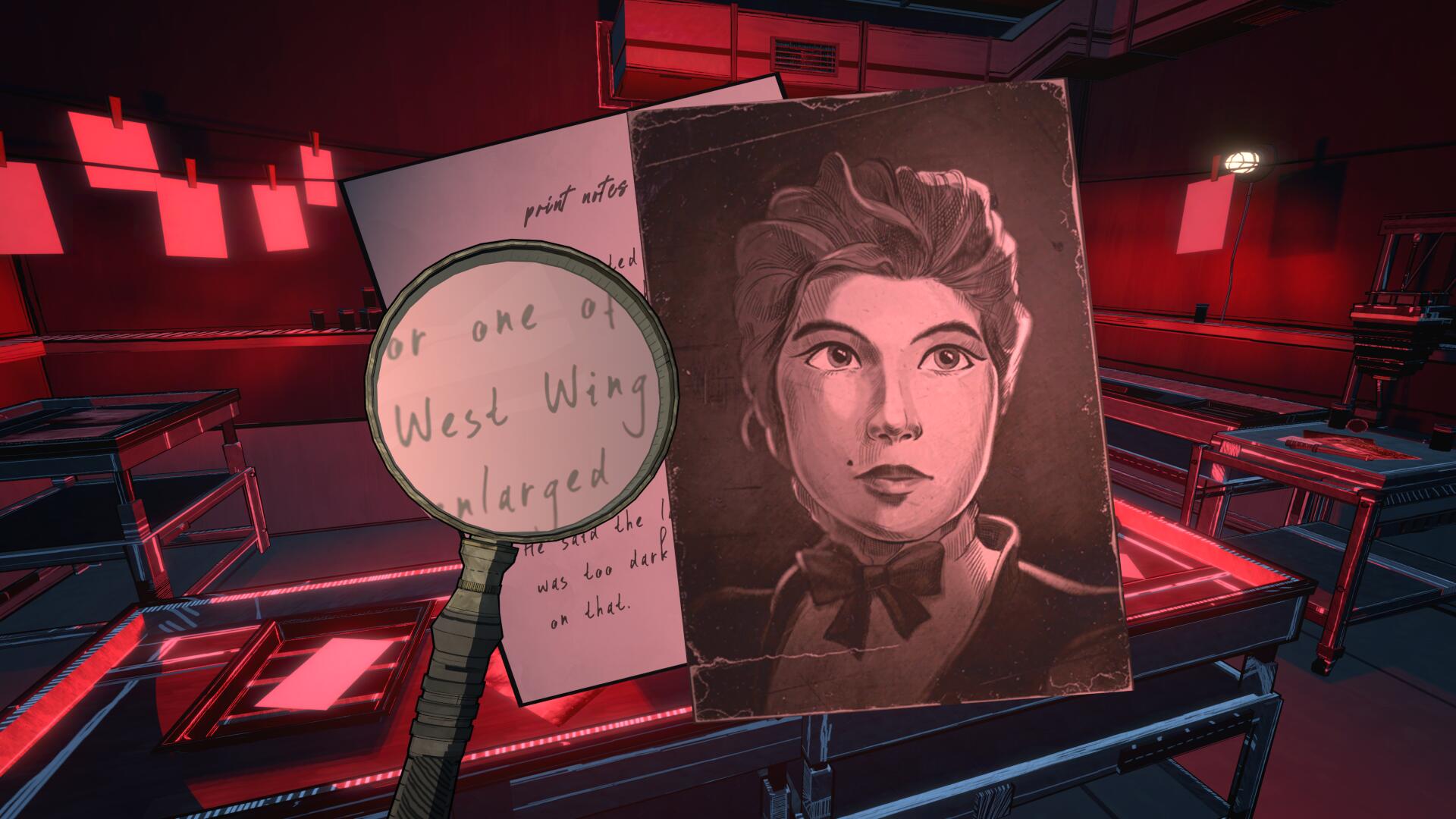

In the roguelike puzzle game, you inherit a house from your great uncle. There's one catch – you need to find the hidden 46th room in this 45 room mansion. That in itself, is quite a creepy premise, with the game’s core loop involving opening a door and then drafting (picking from three blueprints) a room beyond it. You may one day turn left from the entrance hall into a closet, another day into a grand dining room, and another into a spare room, all half-dried paint and unfinished dreams.

As I play it, enjoying its brainteasing puzzles, something about it just doesn’t feel right. It makes me uneasy. All of this makes me think of House of Leaves, the seminal postmodern horror story by Mark Z. Danielewski. In this tome-like book, you’ll find a story within a story: The Navidson Record, which follows the titular Will Navison, a photographer who moves into a new home in Virginia with his family. It quickly becomes apparent that there is something altogether more horrifying about the house, which is seemingly alive. It undulates with ever-changing hallways, doors and other fixtures appearing, changing its interior dimensions without ever changing its exterior ones. One of the key centerpoints of the house is a descent down below it into cavernous depths.

Sound familiar? Mt. Holly’s Foundation room is calling your name.

The house always wins

Blue Prince review: "This exploration roguelike is like nothing else I've played, and became a puzzle obsession I just couldn't shake"

Throughout Blue Prince, I kept half-expecting to run into a monster or some other horror, such is its tone. There’s something undeniably terrifying about the baffling layouts that you’ll find. Perhaps you’ll draft a Great Hall, behind the doors of which you constantly find closets too small to use. Maybe you’ll draft a garage next to a closet, leading from a bedroom. In other games, this would simply be put down as a poor design choice by the environment team, but here it has two creators: you and the house. The house creates itself as much as you do – it's what offers you the choices for each room, after all.

Both of these works blend genres together effortlessly in a way that I’ve only ever seen before in MyHouse.wad, a mod for the original Doom that is directly inspired by House of Leaves. Just as the game isn’t a straightforward puzzle game, the book isn’t a straightforward horror story, either.

House of Leaves can be read not only through countless interpretative lenses, but as entirely different genres. The book appears to be a horror story in both its format and its content, but there’s a lot more to it than that. The main character outside of the Navidson record, for example, lives a chaotic life of meaningless sexual encounters and drug abuse, satirising the vacuousness of gen X life, akin to Fight Club. One of the more popular anti-horror interpretations of the book, however, is of a love story. This love can come from and towards many different characters, but each reading tends to hook onto one in particular.

If House of Leaves, despite its outward appearance, can be a love story, what stops Blue Prince from being a horror game? That, to me, is what sells Blue Prince as the first House of Leaves game, distinct from things like MyHouse.wad, masterful as they are. This capability to read the game as both a puzzle game, abstracted from the spacial horrors within and as a horror game.

Don’t know much trigonometry

There’s a discomfort and an uncanniness in being somewhere so devoid of life while evidently being redolent with it

There's another aspect of Blue Prince that I think lends itself to the horror label, above and beyond its nonsensical spaces that Kubrick would be proud of. Wandering from room to room, it’s hard to feel totally alone. You are met, at reliable points throughout your trips into Mt. Holly, with hints of inhabitants beyond yourself. Food will be served in the dining room, dishes prepared in the kitchen; you’ll find puzzles reset each day, ready to tempt you.

Despite being totally alone, the house shows signs of life, both its own and of other residents. It’s telling that one of my first points of comparison for Blue Prince was the Spencer Mansion from Resident Evil, and not only because opening doors in both games takes center stage at times. There’s a discomfort and an uncanniness in being somewhere so devoid of life while evidently being redolent with it.

In short, play Blue Prince. It’s a sensational puzzle game, but it’s more than that. As with House of Leaves, it’s a title that is capable of occupying multiple and disparate genres simultaneously. In my dreams, I’ve often wondered what lies beyond the extra doors and hidden spaces. In Blue Prince, like in House of Leaves, you get to find out.