On a bracing Hobart morning in autumn, many Tasmanians were greeted with the news that they had been waiting years to hear.

On the cusp of delivering his government's second budget, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has committed $240 million to building a stadium at Hobart's Macquarie Point site, pending the AFL granting Tasmania a licence for a league team.

"The Commonwealth will be providing, in the budget in 10 days time, $240 million of funding for this site and $65 million for the upgrade of UTAS stadium in Launceston as well," Mr Albanese stated.

"We want to make sure that the benefits of having an AFL team based here in Tasmania means that they can play both in Hobart and in Launceston, as well to develop to deliver the economic benefits for the whole state of Tasmania."

The $240m promised is a historic figure, the largest a federal government has ever promised to spend on a football stadium.

The budget promise ticked off the last of 12 "workstreams" the AFL articulated for the entry of a standalone Tasmanian team into the AFL competitions.

It is expected in the coming days that the 18 AFL club presidents will vote to grant Tasmania the 19th AFL licence.

The proposed Tasmanian stadium spending adds to the billions of dollars spent on football stadiums across the country in recent years.

Importantly, the spend on the new Hobart stadium breaks new ground for federal government involvement in spending on football stadiums in Australia.

The spending on Macquarie Point may change the relationship between governments and spending on major sporting infrastructure.

Size of the spend

When the Tasmanian government — led by Premier Jeremy Rockliff — and the AFL — steered by CEO Gillon McLachlan — came hat in hand to the federal government to help Tasmania build big, history suggested their chances were slim.

Ordinarily, the federal government's involvement in sport expenditure is fairly narrowly focused. The government traditionally places funds on three discrete areas in the sporting landscape.

Firstly, there is the Australian Institute of Sport and the system of Australian Sports Commission grants to encourage high performance elite athletes to win medals.

There is also funding given to national sporting organisations for participation in sport. Finally, there is the local grants for infrastructure spend for more minor sporting facilities.

When it comes to major Australian stadiums, most of the money has historically come from state governments.

State and territory governments own and operate the vast majority of football stadiums in Australia, with just Docklands, Dolphin Stadium and Endeavour Field (Shark Park) regularly used privately owned stadiums.

The ABC has calculated that about three quarters of current and committed spending on major football stadiums' most recent works have come from state government funds.

The federal government's commitment to Macquarie Point is roughly double as much funding (inflation-adjusted) as it had ever tipped into a football stadium before.

Outside of commitments made for the 2032 Olympic Games, the proposed federal spend on the Macquarie Point stadium is the biggest single venue spend on record.

A state of limited means

There may be a good reason that the federal government is stepping in to provide funding in this case.

Not all states and territories in Australia are alike. While the Senate gives the same number of seats to Tasmania and NSW, the former has just 570,000 people and the latter has 8.2 million.

Half a billion dollars means different things to different governments. NSW can spend approximately $1 billion (adjusted for inflation) on fully rebuilding Sydney Football Stadium without a huge impact on its economic bottom line.

Financially, Tasmania is one of Australia's three small jurisdictions. This federal funding lets it build like a bigger state, such as NSW or Victoria.

The projected $741 million price tag places the cost of the Macquarie Point project into the same inflation-adjusted range as the 2012 Adelaide Oval redevelopment, the Docklands construction and the recent knockdown and rebuild of Sydney Football Stadium.

It is also far more expensive than the economical build of Brisbane's old workhorse, Lang Park.

It is double the price tag of the North Queensland Cowboys' new home ground, the last major football stadium built outside the big five mainland capital cities.

For Tasmania — even with unprecedented federal support — the projected $375 million and $65 million investments together represent the equivalent of about 5.7 per cent of total annual state spending.

Only Western Australia has spent relatively more on their recent stadium build.

Perth's centrepiece arena on the Swan River was never meant to cost that much. Adjusted for inflation, initial expectations put Perth Stadium around $1.2 billion but post-build estimates placed the final government outlay at $2.2 billion, a 90 per cent increase.

Stadium cost blowouts are relatively common across the country. Most stadium costs increase from initial estimates and not just because of inflation.

Across the 12 largest venues in the sample above, the average cost increase was about 28 per cent.

That sort of overrun would push Macquarie Point to the brink of a billion-dollar construction price tag, with questions around who would foot the extra bill.

Filling up the wallet

The big question that dominates the conversation whenever governments spend money on infrastructure is whether the spend will be value for money.

The Macquarie Point project's own cost benefit analysis suggests it will not make back the value of the money spent over the foreseeable future, which is common to most infrastructure projects.

Ryan Buckland, an economist and principal at ACIL Allen consultants, said it was no surprise an infrastructure proposal like this does not deliver a measurable benefit.

"There's a reason the AFL has been so keen to get public funding support for this project," he said.

"While Australians love their sport, they don't love it enough to pay the true cost of building and operating billion-dollar assets."

The report suggests that over a 20-year period, the project may cost a billion dollars to build and run, then make a billion dollars back, nominally breaking even.

However, the lower value of future money in "present value" calculations means those returns are much less valuable than current money, resulting in costs valued twice as high as benefits.

That nominal break-even value depends on the place actually being used enough. The break-even point is expected to be 44 events a year.

There is also a non-financial element to sporting infrastructure spending. Australia is a sporting nation, and at its heart is the linkage between community sport and those at the top of the tree.

The strong tendency is to win public funding by bringing community purposes into the fold. Examples such as the Red Cross blood donation centre at the new Sydney Swans headquarters to Arden Street's education spaces blend community benefits with elite sporting infrastructure.

"So this is an exciting project," Mr Albanese said.

"It … goes together with the $240 million that we (the government) have for this project that will see here a stadium, that will see housing, that will see private investment as well.

"That will see, importantly, see the port facilities so that we can have greater access to the Antarctic from here as well.

"This is a revitalisation project that will transform this city. This is one that I'm very pleased to support."

The federal government's messaging around Macquarie Point suggests Tasmania, too, must play the community investment game to ride out risks around such a relatively enormous federal and state expenditure.

What's the funding model?

Questions are often asked whether governments must be the ones funding big stadiums.

The two main examples of private funding in Australia are Docklands and Stadium Australia.

Docklands was built at a profit by private investors and eventually bought out by the AFL two decades later. Tenant clubs often felt the financial pain under early tenancy conditions.

On the other hand, Stadium Australia was eventually bought from its investors by the NSW government after profits failed to materialise.

There are also some smaller private stadiums, such as the Dolphins and Sharks' home grounds in the NRL, and Cazalys owned by AFL Cairns.

"Governments are almost always the central funder of sports stadia and arenas in Australia," Buckland said.

"Very few leagues, and fewer teams, can generate the kind of revenue you need to pay for the operations and maintenance of infrastructure, let alone pay back the capital.

"But there are ways sports infrastructure can be delivered which taps both public and private sectors, helps protect taxpayers from risks, and achieve both commercial and social objectives."

The Macquarie Point proposal earmarks $85 million of its budget coming from private partnerships. If achieved, it would represent one of the larger private stadium outlays yet seen, but still not sustain much of the total cost.

"Perth Stadium was delivered utilising a Public Private Partnership," Buckland explained.

"The government pays part of the costs and contracts business to do the rest. Business then takes responsibility for operating and maintaining the stadium and surrounding precinct.

"They also get to keep the revenue associated with the stadium.

"A model like that could work well given what we know about this proposal."

A different world

Government spending on stadiums can be controversial overseas, but in Australia it is rare to see much political blowback. The controversies end up largely forgotten once a footy is kicked.

Australia spends a lot on sport, community and elite. The size and scope of the Tasmanian projects, in a small and disadvantaged polity, may prove more difficult to navigate.

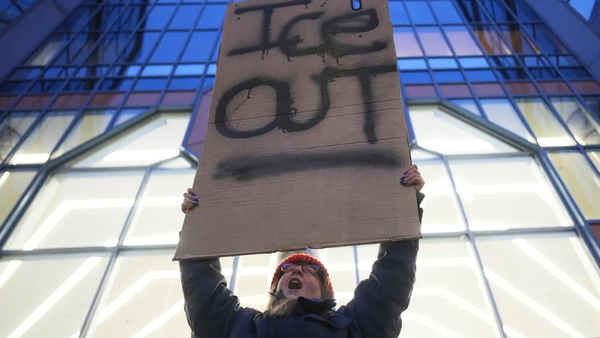

Albanese's announcement was met by a wave of loud protesters, requesting the money be spent elsewhere on hospitals and housing.

Sport administrators regularly argue that their elite-level funding is in service of something greater. Tasmanian football figures have long tied lack of elite representation to falling community participation rates.

Any recent football club headquarters project will show the norm is to win public funding by bringing community purposes into the fold.

The appeal of the Tasmanian AFL team is usually pitched as a way to revitalise a struggling game and engage young people on the ageing and deprived Apple Isle.

Given the federal government has now funded Macquarie Point, other jurisdictions may also come calling for funding.

For example, Canberra Stadium desperately requires upgrades or replacement in order to continue to service the community.

While $240 million might be a drop in the federal budget, multiples of that may have impacts elsewhere on the economy.

Only time will tell how the Tasmanian investment will play out.