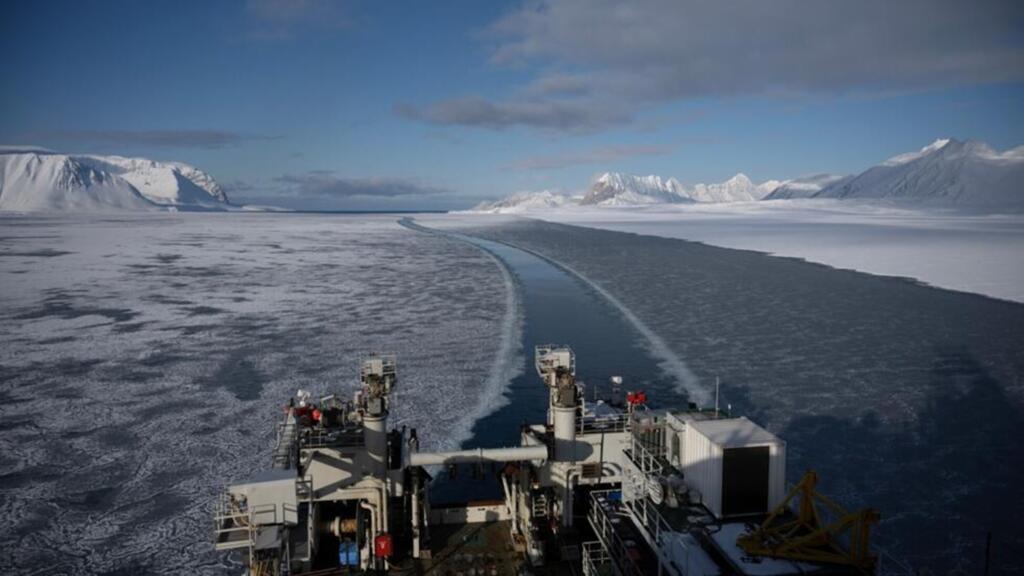

Tensions in the Arctic are putting new pressure on Svalbard, a Norwegian-administered archipelago long seen as an example of international cooperation, as climate change transforms the region and rivalry between major powers intensifies.

Svalbard is often described as the fastest-warming place on the planet. Located close to the North Pole, the archipelago sits on the front line of climate change, a position that has drawn scientists from around the world for decades.

For years, a unique legal status allowed Svalbard to function as a model of global cooperation. But as Arctic ice retreats and geopolitical competition intensifies, the territory is newly vulnerable.

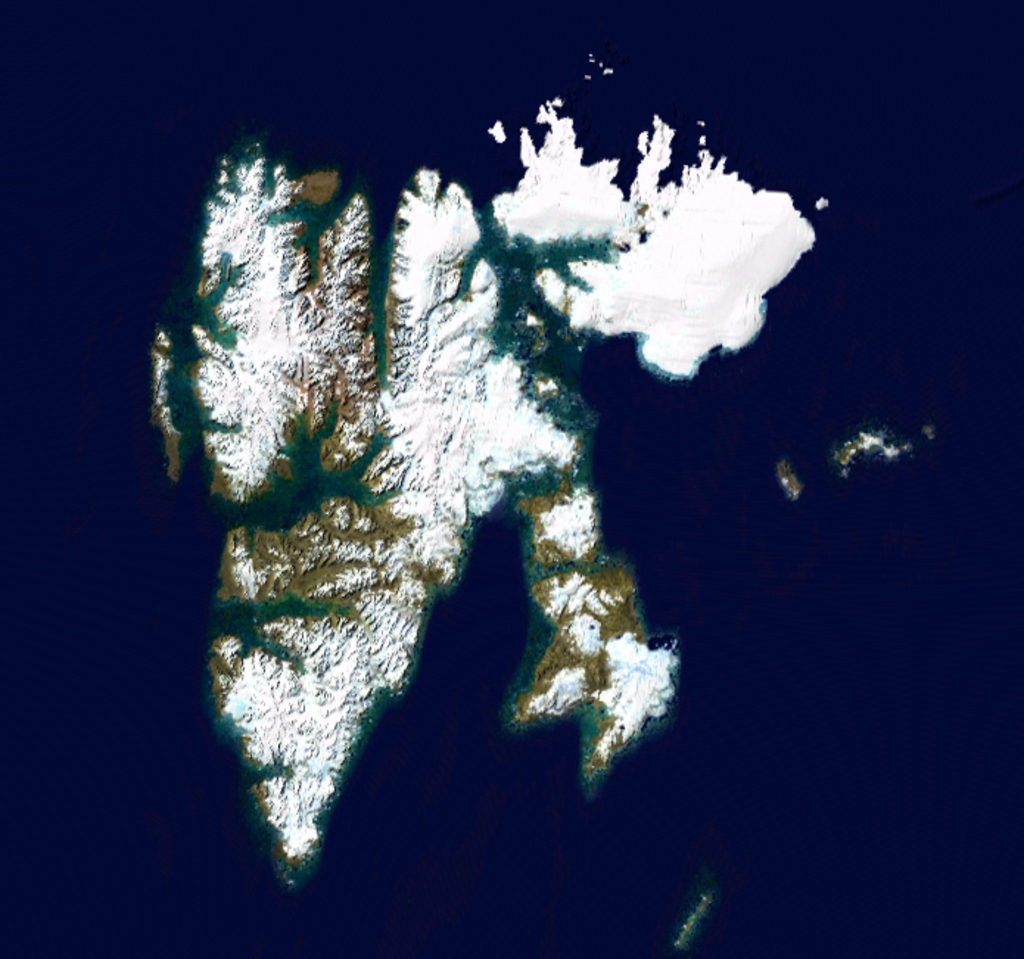

Recent tensions linked to the possibility of a US annexation of Greenland, less than 500 kilometres to the west, have fuelled concern in Norway's media and political circles. Could Svalbard be next?

“Norway has not faced a security situation this serious since 1945,” Eivind Vad Petersson, a senior official at Norway’s foreign ministry, told The New York Times. “When Greenland is hit by a political storm, Svalbard is inevitably splashed as well.”

Svalbard’s sensitivity lies in its legal framework. The Spitsbergen Treaty, signed in Paris in 1920 after the First World War, recognises Norwegian sovereignty over the archipelago, located more than 900 kilometres north of mainland Norway.

At the same time, the treaty strictly limits Oslo’s authority. Citizens of signatory states are placed on an equal footing when it comes to access and activity in Svalbard – including hunting, fishing, mining and land ownership.

Initially signed by around 10 countries including France, Denmark, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and Italy, the treaty now counts nearly 40 signatories. They include Russia, China and North Korea, whose citizens can settle in Svalbard without a visa.

For decades, this system underpinned what many saw as an Arctic laboratory of cooperation. Nowhere symbolised this more than Ny-Alesund, a small research community hosting Chinese, Korean, Franco-German and Japanese scientific stations.

“Svalbard became a hub for research, exchange and the study of climate change. It’s a place where international scientific cooperation can really happen,” Florian Vidal, a researcher at the Arctic Institute of Norway in Tromso, told RFI.

Today, the archipelago – roughly the size of Croatia – has about 2,700 residents, mainly in Longyearbyen, the world’s northernmost town. A study published in January found there are fewer people there than polar bears.

France to step up Greenland deployment with land, air and sea forces

Strategic ambitions take shape

In recent years, the Arctic as a region has become more politically charged. Once seen as remote, it has become a key arena of international competition at a time when the global order is shifting.

Security concerns, new maritime routes and access to resources have all raised Svalbard’s profile. Seabeds around the archipelago are believed to contain copper, zinc, cobalt, lithium and rare earths – seen as strategic for new technologies and the energy transition.

While extraction is limited by moratoriums, several major powers, including China and the US, are already looking further ahead.

Russia has played a central role in the rising pressure. “Tensions around Svalbard have existed since the 2010s, but they clearly accelerated after the annexation of Crimea and then with the war in Ukraine,” Vidal said.

In February 2024, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Yury Trutnev warned that Moscow would fight for its “rights” in Svalbard, invoking the need to defend its “sovereignty” over the archipelago, in rhetoric echoing language used to justify the war in Ukraine.

The message was repeated in November, when Trutnev again stressed Svalbard’s strategic importance for Russia and the need to maintain a stronger presence, particularly through the state mining company Arktikugol.

Russia maintains two settlements on Svalbard – Barentsburg and Pyramiden, home to several hundred Russian citizens. Officially tied to coal mining, the sites are remnants of the Soviet era, with the mine in Pyramiden closing at the end of the 1990s.

“The Russians are artificially maintaining the Barentsburg mine to justify keeping a presence,” Vidal said.

Why Greenland's melting ice cap threatens humanity, and could serve Trump

Testing Norway’s red lines

In recent years, these communities have become the stage for symbolic gestures viewed by Oslo as provocative.

In Barentsburg, where the Russian flag flies, a parade was held in 2023 to mark Victory Day on 9 May, celebrating the defeat of Nazi Germany. There were no weapons, but the military-style staging and symbols were seen by Norwegian authorities as a political message.

Vidal also pointed to the use of security vehicles with visual codes close to those of Russian forces, and to the growing prominence of the Russian Orthodox Church. A full-time priest has been permanently based in Barentsburg since March 2025.

This helps anchor Svalbard in an image of “Russian land”, Vidal said. “These episodes fit into a logic of hybrid warfare. The Russians are testing the limits of Norway’s sovereignty over the archipelago.”

The message, he added, is unambiguous: "The Russians are there, and they are not leaving.”

Svalbard also holds military significance for Moscow. Nuclear submarines from Russia’s Northern Fleet, the country’s main Arctic naval force, are based in Severomorsk in northwest Russia and must pass near the archipelago to reach the Atlantic, making it a key transit point.

France to open Greenland consulate amid Trump takeover threats

Oslo reasserts control

Faced with these signals, Norway has moved to reassert its authority without formally challenging the 1920 treaty. In a strong symbolic move, King Harald V visited Svalbard in June for the first time in 30 years.

“America has gone mad in the Arctic and Russia does not respect the independence of its neighbours. It is very important to send the king to mark the kingdom’s supremacy over its distant territories,” Norwegian daily newspaper Verdens Gang said.

“There is a form of nationalism around Svalbard on the Norwegian side, it’s a very sensitive issue,” Vidal said.

Norway has also strengthened coastguard patrols around the archipelago. Moscow has protested, arguing this violates the treaty’s ban on military use.

While permanent militarisation is prohibited, naval patrols are not explicitly banned – a legal grey area Norway now relies on.

Administrative controls have also tightened. Local voting rights have been restricted to foreigners who have lived for several years on mainland Norway, and land sales to non-Norwegians have been banned.

Scientific research is now more closely supervised, with projects requiring approval from Oslo. “We are seeing a gradual extension of Norwegian prerogatives,” Vidal said, describing a “Russian-Norwegian ping pong game”.

Rare earths mining feud at heart of Greenland's snap elections

Pressure from multiple sides

China’s presence is also viewed with growing caution. Beijing has been a signatory to the Spitsbergen Treaty since 1925, and has operated a research station in Ny-Alesund since 2004.

Officially dedicated to polar science, the station is suspected by Norwegian and US authorities of carrying out research with potential dual use.

Two granite lion statues have become a symbol of friction, with China refusing Oslo’s requests to remove them. In summer 2024, more than 180 Chinese tourists arrived in Ny-Alesund, displaying national symbols.

One woman posed in military-style clothing in front of the statues, triggering diplomatic unease.

Norwegian authorities have also, for the first time, denied Chinese students access to the University Centre in Svalbard, citing security risks.

Svalbard has also long been a point of tension between Norway and the European Union. Several EU member states contest fishing quotas and permits imposed by Oslo around the archipelago, arguing they breach the treaty’s principle of equality.

The EU has also raised concerns over Norway’s seabed prospecting campaigns near Svalbard.

Against this backdrop, tensions surrounding Greenland have revived fears of imitation. If US President Donald Trump were to seize Greenland in defiance of international law, could Russia feel justified in challenging the status quo in Svalbard?

“We are not in a critical phase, but in a crisis that is gradually building,” Vidal said.

One strategic question remains unresolved. In the event of an attack, would NATO’s Article 5 – its collective defence clause – apply to an archipelago with demilitarised status?

Aware of this uncertainty, Norway has stepped up political signalling in recent years, including hosting delegations from NATO’s parliamentary assembly in Svalbard, without ever securing a formal guarantee.

This article has been adapted from the original version in French by Aurore Lartigue