Noise was first considered a public health issue in interwar Britain – called the “age of noise” by the author and essayist Aldous Huxley. In this era, the proliferation of mechanical sounds, particularly the rumble of road and air traffic, the blare of loudspeakers and the rising decibels of industry, caused anxiety about the health of the nation’s minds and bodies.

Interwar writers, such as Virginia Woolf, George Orwell and Jean Rhys, tuned in to the din. Their fiction is not just an archive of past sound-worlds but also the place where sound became noise and vice versa. As sound historian James Mansell has argued: “Noise was not just representative of the modern; it was modernity manifested in audible form.”

We now have more data and scientific evidence on the effects of environmental noise. The World Health Organization recognises noise, particularly from road, rail and air traffic, as one of the top environmental health hazards, second only to air pollution.

In the interwar period, without comprehensive data on noise and health, early campaigners relied on narrative. They created a particular story about noise and nerves to galvanise the public into keeping it down.

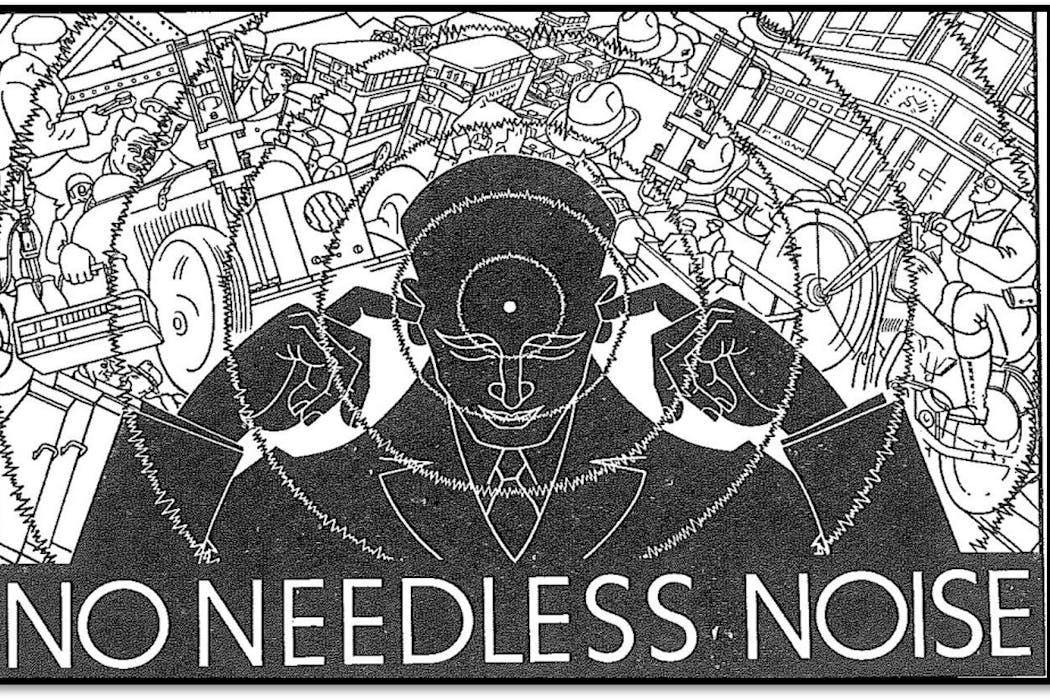

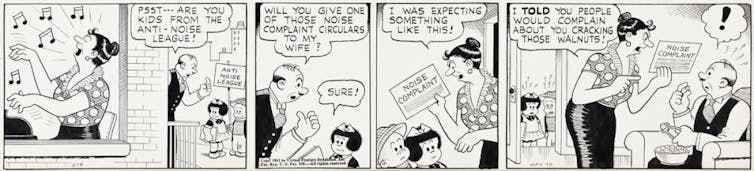

In 1933, the first significant UK noise abatement organisation, the Anti-Noise League, was founded by physician Thomas Horder. The league consisted of doctors, psychologists, physicists, engineers and acousticians (physicists concerned with the properties of sound) who lobbied government for a legislative framework around noise.

They sought to educate the public on the dangers of needless noise through exhibitions, publications and their magazine, Quiet.

Their campaigns drew attention to the very real health effects of environmental noise. But they also saw noise as waste: something to be eliminated in the pursuit of a maximally productive and efficient citizenry.

They drew on ideas of Britishness associated with what they called “acoustic civilisation” (or teaching the nation to be quieter) and “intelligent” behaviour to enact a programme of noise reduction as sonic nationalism.

Noise in modernist fiction

This interwar preoccupation with unwanted sound is also a sonic legacy of the first world war. Exposure to the deafening din of artillery, exploding shells and grenades caused catastrophic auditory injury. So much so, that the din was associated with loss of life and the devastating effects of shell shock.

The extreme noise of warfare also pushed doctors and psychologists to study how sound affects health. This work continued into the 1930s through government-backed bodies such as the Industrial Health Research Board. As a result, people in the interwar years became much more aware that the everyday sounds of machines and traffic could also be harmful.

But it wasn’t only doctors and acousticians who wrote about noise. Authors such as Rebecca West and H.G. Wells worked with the Anti-Noise League, while others, like Winifred Holtby, publicly refuted their findings. But more broadly, in the pages of interwar fiction, modernist writers engaged deeply with the shifting noisescapes around them.

The unprecedented noise levels of the wars, together with the proliferation of sounds in urban and domestic spaces and the auditory training required by new forms of sound technology, caused an attentiveness to sound and hearing. This was harnessed both metaphorically and structurally in the period’s literature.

Modernist writers such as Woolf, Orwell and Rhys listened intently to machines and the sound worlds they created. Once we start to listen for it, noise is everywhere in fiction of the period.

Proletarian factory novels of the 1930s such as Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole (1933) or John Sommerfield’s May Day (1936) draw new attention to toxic and harmful high decibel industrial environments.

Interwar novels such as Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (1925) or George Orwell’s Coming Up for Air (1939), each with first world war veteran protagonists, register urban noise via the auditory effects of the conflict zone, or a kind of communal noise sensitivity, as well as through the healing or connective properties of sound. In Dorothy Sayers’ Nine Tailors (1934) a character is (spoiler alert) killed by the sound of a church bell.

Rhys’ short story Let Them Call It Jazz (1962) is set in London in the years following the second world war. It depicts the hostile environment faced by immigrants, such as those arriving from the Caribbean on HMT Empire Windrush, as protagonist Selina Davis is imprisoned for noise disturbance. She has been singing Caribbean folk songs in a “genteel” suburban neighbourhood.

The tale is one of cultural identity, the resistant power of sound, and the politicisation of noise. Black music is a form of sonic resistance; noise is both a silencing strategy for bodies and practices deemed “aberrant” and a resistant practice that exceeds and disrupts exclusionary codes of value and hierarchy.

These works, and many more, demonstrate that modernist writers, if we listen carefully, are theorists of sound who responded in complex ways to their shifting soundscapes. They counter the association of noise with negative affect or “unwanted” excess, by finding aesthetic and political possibility in noise.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Anna Snaith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.