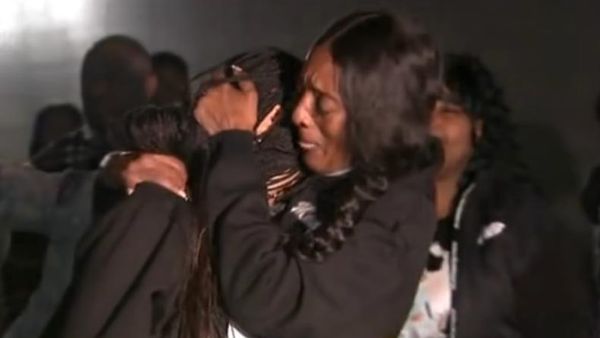

The historic disarmament ceremony on July 11 where members of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) laid down their arms marked a pivotal moment in a decades-long conflict in Turkey. The ceremony was described by many who attended as a profoundly symbolic and emotional day that may signal the beginning of a new era.

During the disarmament ceremony in Sulaymaniyah in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, 26 PKK guerrillas alongside four senior commanders and leaders of the movement, symbolically laid aid down their arms and burned them. The audience included officials from the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), plus politicians, journalists and international observers.

For more than four decades the PKK has been embroiled in an armed conflict with Turkey that has claimed more than 40,000 lives and shaped Kurdish identity and politics across the region.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

The PKK disarmament ceremony also could mark a new era for the Kurds, one of the largest stateless groups in the world with over 30 million people living across Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria. The PKK has said it will now shift from armed resistance to political dialogue and regional cooperation.

Strikingly, the day after the ceremony, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan acknowledged the state’s historical failures in addressing the Kurdish issue. He listed past abuses of Kurds – state-sponsored abductions and extrajudicial violence, the burning of villages and the forced displacement of families – as examples of policies that had fuelled, rather than quelled, the conflict.

“We all paid the price for these mistakes” he said. He later added: “As of yesterday, Turkey began to close a long, painful and tear-filled chapter.” Erdoğan also announced the formation of a parliamentary commission to oversee the legal steps of the peace process, suggesting a much-needed institutionalised and transparent approach than in previous attempts.

This hints that the road ahead might include a period of transitional justice. This could compose of different tools used by societies to address past violence and human rights abuses during a shift from conflict to peace and democracy. These may include legal actions such as trials, as well as other efforts to heal and rebuild trust in society.

Erdoğan also underlined the regional dimension of the agreement: “The issue is not only that of our Kurdish citizens, but also of our Kurdish brothers and sisters in Iraq and Syria. We are discussing this process with them, and they are very pleased as well.”

International dimensions

While the PKK may be laying down arms, the Kurdish political movement should not be expected to disappear. On the contrary, it is likely to become more active in the democratic sphere — both in Turkey and in other parts of the Middle East where Kurdish people live. It is no secret that the current peace process is the result of shifting geopolitical realities.

Growing tensions between the US and Iran, Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, the ousting of the Assad regime in Syria, and shifting power dynamics across the region have all contributed to a geopolitical landscape in which prolonged armed conflict has become increasingly unsustainable — for both Turkey and the PKK. In this context, the current peace process is not merely a domestic initiative.

It represents a strategic recalibration in a rapidly changing Middle East. For Turkey, stabilising its southeastern border and reducing internal security pressures is essential amid regional volatility.

Turkey has long maintained strong ties with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) (the official ruling body of the Kurdistan region) in Iraq. However, the situation for Kurds in Syria remains more complex, as Turkey continues to view the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (a region that has in effect been self governing since 2012 and where many Kurds live) as a security threat along its border.

Meanwhile, negotiations continue between the new Syrian government under current president, Ahmed Hussein al-Shara, and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the Kurdish-led coalition in Syria, which has been historically backed by the US. The SDF seeks to maintain its military autonomy and have its own independent political system — both of which are opposed by Damascus.

Western nations, particularly the US, remain influential in these talks. The US ambassador to Turkey and special envoy for Syria, Thomas Barrack, is reportedly uneasy with the lack of progress in the talks between al-Shara, and the SDF. He said: “The SDF, who has been a valued partner for America in the fight against ISIS, well-respected, bright, articulate, has to come to the conclusion that there’s one country, there’s one nation, there’s one people, and there’s one army.”

Another factor here is that a strong Arab-Turkish-Kurdish alliance is unlikely to align with Israeli strategic interests, which may favour a more fragmented Kurdish presence in the region.

For now, Turkey faces the complex task of overseeing a comprehensive disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration process. This requires not only the decommissioning of weapons and the disbanding of armed units, but also the social and political reintegration of former combatants. The success of this will depend on legal reforms, institutional trust and a genuine commitment to democratic inclusion.

Erdoğan has been critised for his government’s ongoing non-democratic practices such the appointment of state trustees who replace elected officials and the imprisonment of elected officials.

And, despite the symbolic disarmament, the Turkish government persists in using the words “struggle against terrorism” — an approach that risks undermining the peace process by criminalising political dialogue and delegitimising Kurdish demands.

Turkey’s foreign minister Hakan Fidan reiterated that the PKK’s broader network, including the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK), a group representing Kurds across Iraq, Syria and Turkey, must cease to pose a threat. “We will remain vigilant until every component of the KCK is no longer a danger to our nation and region,” he stated.

For the PKK, the changing alliances and uncertainties in Syria and Iraq may have made armed struggle a less viable path forward. Yet the sustainability of peace will depend on more than disarmament. It will require ending the criminalisation of Kurds in political institutions and within civil society.

What comes next will determine whether this moment becomes a historic turning point or another missed opportunity.

Pinar Dinc is the principal investigator of the ECO-Syria project, which receives funding from the Strategic Research Area: The Middle East in the Contemporary World (MECW) at the Centre for Advanced Middle Eastern Studies, Lund University, Sweden.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.