Hannah Kent is the reason I went to Iceland. Her award-winning first novel Burial Rites (2013) is a speculative biography of the murderer Agnes Magnúsdóttir, the last woman to be executed in Iceland. The novel is often set for VCE English in Victoria and I picked it up because my son was studying it. We had already planned a trip to Europe to celebrate the end of school. After discussing Burial Rites with him across the year, it seemed right to add some days in Iceland to our itinerary.

It’s fair to say that Iceland is not on the radar of most Australians. The most common response I received when sharing our travel plans was confusion. But having visited that small island with its massive snowdrifts, frozen waterfalls, blasts of icy wind, fascinating people and magic lore, I can understand why it has taken root in Kent’s imagination.

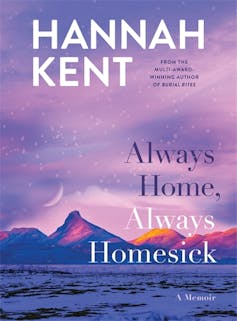

Review: Always Home, Always Homesick – Hannah Kent (Picador)

Kent has published two novels since Burial Rites: The Good People (2016), set in Ireland, and Devotion (2021), set in her own South Australia. But it is clear from her new memoir Always Home, Always Homesick that Iceland exerts the strongest pull on her, defining and dividing her identity as a writer. Perhaps most surprisingly, it becomes clear through the memoir that Kent remains haunted and, as she puts it, “enthralled” by the spectre of Agnes Magnúsdóttir.

A bookish young woman abroad

The memoir opens in 2020 with Kent, her wife and small children in lockdown in South Australia due to COVID-19, but it is structured around three trips to Iceland.

Kent’s first visit was as a teenage Rotary exchange student. The second was her research trip as a Creative Writing doctoral student, exploring the historical sites and archival sources associated with Agnes’ crime, conviction and execution. Finally, having established herself as an author with Burial Rites, she returns as an invited speaker at a literary festival.

I was amused by Kent’s account of herself as a bookish young woman who, with faultless logic but no real understanding of what she was getting into, selected northern European countries with the harshest winters as preferred sites for her exchange. The idea was they would provide the greatest contrast (and the most culture shock) for a girl who had never seen snow.

I also identified with Kent’s account of her disorientation on arriving at the tiny Keflavik airport. Expecting a large customs hall, she finds a seemingly never-ending corridor, culminating in an open area with only a set of electric doors between her and the car park. To this day, I remain bamboozled by Iceland’s casual disregard of passport checks. As the mother of an emerging adult, I was horrified by the idea of a young girl arriving at the opposite side of the world with nobody to collect her, ingenuously asking the security guard if she should wait outside.

The ease with which the security guard finds Kent’s missing host attests to the country’s sparse population. Part one of Always Home, Always Homesick charts her progress from a lonely and alienated teenager, placed with a kind but distant Icelandic family, to acceptance. She describes the growth of long-lasting friendships at her new school, and her move into a new inclusive family with Pétur, Regína and their noisy, chaotic, loving children.

The depth of Kent’s connection to the small community of Sauðárkrókur and the genuine love and affection that develops between her and her host family bind her to Iceland.

Also significant is her impressive, if at times self-doubting, grasp of the complicated Icelandic language. When Kent returns to Iceland as a doctoral student, her ability to speak the language gives her access to Icelandic books and records on Agnes Magnúsdóttir. It validates her in the eyes of the Icelanders she meets, granting her something close to insider status. This encourages locals to help her with her research, to share their stories and native insights.

Murder and meticulousness

When I first read Burial Rites, what struck me was its similarity to Alias Grace (1996), Margaret Atwood’s historical novel about the Canadian murderer Grace Marks. Like Atwood’s novel, Burial Rites seeks to reclaim its subject’s life. It centres Agnes as the teller of her own story – a story whose details have been lost to authorised history.

For Kent, the essential and often overlooked context for the murder at the centre of the novel is that Agnes and her fellow servant Sigrídur Gudmundsdóttir were trapped by laws that meant they could not leave the farm without the consent of their erratic and violently abusive master, Natan Ketilsson.

Kent describes Burial Rites as speculative biography, but the novel is based on meticulous research. Part two follows her journey as she retraces Agnes’ life from Ketilsson’s farm to her place of execution in 1830 and the burial of her remains. In fact, Agnes threatens to overturn the focus of the memoir from a story of Kent’s life into a companion to the writing of Burial Rites.

This aspect of the memoir is likely to prove useful for teachers and students studying the novel, as it provides a firsthand account of how Kent uncovered the historical facts surrounding the life of Agnes.

Agnes’ supernatural influence irrupts into the story with an uncanny account of the finding of her severed head. The story suddenly shifts the memoir from the familiar and safe realism of life writing to something nearer Icelandic tales of magic and lore.

At several points – for example, when Kent describes the Icelandic rites of Christmas with the trickster “Yule Lads” (Jólasveinar) and the wonderful tradition of “Yule Book Flood” (Jólabókaflóðið), in which people exchange books on Christmas Eve and spend the evening reading – it becomes apparent just how different Icelandic culture is from suburban Australia.

The final part of the memoir covers the publication of Burial Rites, its first award, and its translation into Icelandic as Náðarstund (literally “a moment of grace”). Now a recognised writer, Kent is invited to an Icelandic literary festival, where she contrasts the relatively impoverished status of literature in Australia with the importance of books and writing in Iceland, where literature is supported by generous government grants and honoured with the gracious presence of Iceland’s first lady at a formal reception.

Kent also reflects on the complexities of her divided authorial identity and the way she “troubles” the boundaries of national identity. This in-between status is expressed in the paradoxical title of the memoir: Always Home, Always Homesick.

In fact, I suspect the distance between Kent’s Icelandic story and Australian literature is not as great as she suggests. In Burial Rites, the landscape defines the way the characters live, particularly in a hard winter, and drives the development of relationships between characters. One of the defining characteristics of Australian literature is also its frequent use of harsh and forbidding landscapes to shape people’s lives.

The memoir ends with Kent revisiting Þrístapar, the place of Agnes’ execution, which she first glimpsed from the back seat of a car as a homesick exchange student. Here Kent finds evidence of her work’s influence on her adopted homeland: the path to the execution site is now marked with plaques engraved with quotations from her own novel.

Reading Kent’s memoir often revived for me the experiences my family enjoyed in visiting Iceland. This included tasting Hákarl, small cubes of fermented shark that locals take a cruel delight in presenting to newcomers, surreptitiously watching the reaction as they put it in their mouths. For the record, my son managed to keep it down, but my husband (like Kent) spat it across the room.

What Kent’s memoir provides, however, is something no tourist can hope to experience. She captures the warmth of the Icelandic people towards those they accept as their own and provides an absorbing insight into a culture in which the mystical and magical lie just below the surface of the everyday.

Sharon Bickle does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.