Through the 2000s, animated films continued to mature, and international cinema made a significant impact. India and Japan continued to produce animation, and there was newfound success in the release of Pokémon and Digimon movies. Notably, the decade also saw the release of Alpamysh, the first animated feature produced in Uzbekistan. Reflecting on this growth, critics often compare these works to the overlooked animated films of the ’90s, showing a continuity of craft and storytelling excellence.

American films continued to be abundantly produced, and longstanding animation director Don Bluth released the science fiction animated movie Titan AE. Other notable American animated films of the decade included Robots, The Simpsons Movie, and Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. Richard Linklater ventured into the medium with his experimental films, Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly. Advances in production technology also expanded what was possible, with studios increasingly relying on the best animation software.

A number of animated movies also underscored how it was a medium that could be deployed in the service of stories not solely intended for young audiences. Animation and political engagement have a long history, and the film Persepolis continued this tradition. In many ways, this was the decade that taught Disney animated films can be more than slapstick gags and cute songs, and be successful doing it.

Chicken Run

Chicken Run won the Critics’ Choice Movie Award for Best Animated Feature. A sequel to the movie, titled Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget, was released in 2023.

DreamWorks / Aardman Animation (2000)

Chicken Run stands as a major British animated movie. It had been a sketch of Nick Park’s that had sparked the concept. It showed a chicken digging under a wire fence with a spoon. In these brand new comments and recollections for this article, Peter Lord (co-founder of Aardman) looks back on Chicken Run.

“When we first presented the idea of Chicken Run to Hollywood execs, Nick and I had the best movie-pitch ever: 'We’re going to make the Great Escape […] with chickens.'”

As pitches go, they don’t get much better.

"So we got the gig. All we had to do now was make the film. Chicken Run had an amazing impact on the Aardman studio, on what we could do and how we do it. When I think about it now, I just marvel at how much we had to learn when we started, in every department – in animation, storyboarding, puppet-making, storytelling - everything. These were all processes we knew, but the sheer scale of feature production took us by surprise. And there were fundamental questions: we couldn’t be entirely sure how our beloved stop-frame technique would translate to cinema. Remember the heads of our stars – Ginger and Rocky - were only about two inches tall and made of modelling clay. The animators’ fingerprints were fully visible. How would that work when they’re 20 feet high on the big screen? Well it did. It worked brilliantly.

"But we didn’t have enough animators. We had a small, close team of maybe seven or eight regular animators, but we knew very quickly that we’d need more – many more! So, we organised an intensive training course to take young graduates from film and art schools and train them in the art of puppet animation. And these new people became the very heart of the Aardman studio. Many of them are working with us still, and that’s a huge part of the legacy of the movie.

"Nick Park and I had loads of ideas – mostly for jokes – and we really benefitted from the writing of Karey Kirkpatrick who brought some Hollywood flair to our screenplay. I mean did we even have a love story at the start? Yes, but not a very convincing one.

"And when the movie came out, it exceeded expectations. It looked amazing on the big screen, and audiences all over the world loved it.

"Since we started on this road, we’ve made seven further claymation movies, using all the talents and skills of our brilliant film-making team and constantly bringing in new people with different experience and expertise. All that creativity, and all that employment in the studio wouldn’t have been possible without the pioneering work that went into Chicken Run.”

Read our feature, 'Inside Aardman Animation' for more.

Shrek

In the spring of 2025, a teaser trailer for Shrek 5 arrived online to great interest with a fair amount of comment being offered up about the adjustments to the character designs of Shrek, Princess Fiona and Donkey.

DreamWorks Animation (2001)

The character and his world have been hugely popular since the first film’s release almost a quarter of a century ago. Initially, the film was going to be a combination of live action, stop motion and computer-generated elements. Two key influences on the film’s visual language were the American painters Grant Wood and N.C.Wyeth.

For Joe Bumpus, CG Supervisor at NEG Animation, “The background characters and human generics from Shrek certainly stand out to me due to their unique design, through costume, hair and animation performance. In the film, characters from familiar from children’s books and tales are met with a comical observation of both real life and fantasy stereotypes.

"These stereotypes are challenged, broken and, literally, transformed into grotesque versions of themselves that have helped inspire me not to accept the normal just because it’s normal. This mantra helps me confront the usual conventions of tools and workflows, as well as the methods by which we can reach a solution.”

The Triplets of Belleville

Sylvain Chomet’s new film, The Magnificent Life of Marcel Pagnol, is due for release later in 2025.

Les Armateurs (2002)

The film’s director, Sylvain Chomet, has had a successful career as both animator and comic book artist. Virtually without dialogue, Belleville Rendezvous tells the story of a boy named Champion who lives with his grandmother, Mme Souza. She buys him a bike and then proceeds to train him like crazy to be a competitive cyclist.

For Bridget Dash, Senior Talent Acquisition Partner at DNEG Animation, “When The Triplets of Belleville premiered, I had never seen anything, anything like it before. I grew up a Warner Bros. and Disney kid who also watched every anime, and this film completely flabbergasted me.

"Its storytelling was nearly wordless, its pacing strange, sometimes quiet and slow, other times wild and surreal, like a Max Fleischer cartoon on drugs. The character designs are both unsettling and charming: grotesque yet deeply expressive. In America, especially, audiences didn’t quite know what to make of it. But for a while, it was everywhere, a film people couldn’t stop talking about, and people tried to bring it up in conversation just to show how cultured they were.

"Like Miyazaki’s work, Triplets helped elevate animation beyond the medium, genre & perceived age bracket stigma that animated movies carry. It wasn’t just a cartoon. It was cinema for adults and kids alike. It belongs in the same breath as Spirited Away, Fantasia, Ernest & Celestine, or Akira… films that proved animation isn’t a style, it’s a language. Do yourself a favour: watch The Triplets of Belleville and get lost in it, and man, does that score still slap.”

Spirited Away

Spirited Away won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature and remains the only hand-drawn animated feature to win that award.

Studio Ghibli (2001)

Hayao Miyazaki’s masterpiece doesn’t rely on spectacle or obvious plot mechanics; instead, it invites us into a world that is at once enchanting, unsettling and emotionally precise. Its global success wasn’t accidental, audiences connected to its honesty, imagination and quiet emotional logic.

The story follows Chihiro, a ten-year-old girl who wanders into a spirit realm after her parents become lost and mysteriously transformed. Unlike typical fantasy heroes, Chihiro isn’t gifted with magic or extraordinary abilities. Survival comes through observation, patience and compassion. Whimsy and menace exist side by side: spirits are sometimes grotesque, sometimes tender, and danger often emerges without warning. It’s a world that feels alive because it is neither sanitised nor explained beyond necessity.

Miyazaki’s influence on Western animation, particularly Pixar, is widely acknowledged, from visual language to narrative philosophy. Spirited Away (one of the best anime films) is less about dramatic escalation than emotional truth. Chihiro’s ordinariness is central to that ethos. As Miyazaki himself said: “With Spirited Away I wanted to say to them ‘Don’t worry, it will be all right in the end, there will be something for you’, not just in cinema but also in everyday life. For that, it was necessary to have a heroine who was an ordinary girl, not someone who could fly or do something impossible.”

The film’s lasting power lies in that quiet generosity. Courage doesn’t need to be loud to be transformative; resilience, empathy and small acts of bravery are enough to carry a story, and a viewer, through a magical, sometimes frightening, journey.

Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron

Discussing the film’s production, co-director Lorna Cooke noted that, “We've had eight weeks of ramp-up time for the animators. They were studying horses, drawing from life. A series of Spirit films has been produced.

DreamWorks Animation (2002)

Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron feels like an outlier from another timeline, one where mainstream animation trusted imagery, pacing and mood more than wacky punchlines. This cel-animated DreamWorks Western didn’t arrive with a wisecracking mascot or a barrage of pop-culture gags. Instead, it leaned hard into visual storytelling that recalls animated films of the 1980s, and that creative confidence is a big reason it still holds up.

At its core, Spirit tells a simple story about a wild mustang captured by the US Cavalry, who resists being broken, and forms a fragile connection with a young soldier torn between obedience and empathy. What made the film stand out then, and still does now, is its refusal to anthropomorphise in obvious ways. The animals never speak aloud or interact through dialogue. Spirit’s perspective is conveyed primarily through physical performance, framing and rhythm, with only sparse internal narration used to gently guide the audience rather than explain every emotion.

That restraint gives the film real weight. The animation lingers on tension and stillness, trusting viewers to read meaning in posture and movement. The vast American landscapes, inspired by classic Western cinema, aren’t just backdrops; they reinforce the themes of freedom, control and displacement that sit beneath the adventure.

Hans Zimmer’s score, paired with Bryan Adams’ songs, supports the emotional arc without overpowering it, allowing the film to breathe. It’s animation unafraid of silence.

The lasting appeal of Spirit, evident in its spin-offs and devoted following, comes from that clarity of vision. It’s a reminder that animated films don’t need to shout to endure. Sometimes, the boldest move is letting the image do the talking.

Ice Age

Chris Wedge, the director of Ice Age, was co-founder of Blue Sky Studios where Ice Age was produced.

20th Century Fox Animation (2002)

Ice Age arrived as a quietly pivotal moment for feature animation. Before it became a sprawling franchise, the original film was a modestly scaled road movie set against a frozen prehistoric world, driven less by spectacle than by character chemistry.

The story pairs Manny, a solitary woolly mammoth scarred by loss, with Sid, an endlessly talkative sloth who mistakes companionship for survival. Their unlikely alliance begins as an inconvenience and gradually hardens into something resembling family. The arrival of Diego, a sabretoothed tiger with divided loyalties, adds tension and moral weight, shifting the film away from pure comedy into something more emotionally layered than its premise suggests.

Visually, Ice Age made a deliberate break from realism. The characters are exaggerated almost to the point of caricature, with elongated limbs, oversized eyes, and elastic expressions, but that abstraction is precisely what gives them emotional range. Manny’s heaviness reads as grief. Sid’s awkward posture becomes vulnerable. The design language prioritises readability and feeling over anatomical accuracy.

The environments, by contrast, are cool, crisp and technically ambitious. Blue Sky Studios used advanced light simulation and ray-tracing-based rendering techniques to model how light scatters across ice, snow and stone, giving the film a distinctive clarity and depth. Reflections, translucency and soft shadows aid storytelling, grounding the heightened characters in a believable physical space.

What made Ice Age endure isn't just its humour or novelty, but its balance. Beneath the jokes and set pieces is a film about displacement, trust and chosen family; these are ideas that carry as much by design and lighting as by dialogue.

The Corpse Bride

The film was produced in London. Horror movie legend Christopher Lee voices the character of Pastor Galswells for the film. The Corpse Bride was the first stop motion animated film to be edited using Apple’s Final Cut Pro software.

Warner Bros. Animation 2005

In 2005, Tim Burton returned to the darkly whimsical animated Gothic style that made The Nightmare Before Christmas a cult classic with The Corpse Bride. Shot in London using painstaking stop-motion techniques, the film brings a European folktale to life with the meticulous, tactile charm that only handcrafted puppetry can provide. Burton’s signature aesthetic, angular, elongated figures, shadow-heavy sets, and moody colour palettes, is on full display, creating a world that is eerie, romantic, and visually unforgettable.

The story follows Victor, a nervous groom who inadvertently pledges himself to a deceased bride, plunging into a macabre underworld that mirrors and exaggerates the anxieties of the living world. The humour is pitch-black, the romance bittersweet, and the visuals lean fully into Gothic excess: skeletal ensembles, twisted landscapes and a sense of charmingly grotesque exaggeration.

Animation scholar Dr Chris Holliday notes: “The influence of The Corpse Bride has, perhaps, been somewhat forgotten amid the recent global renaissance that would rapidly take hold of animation. The Corpse Bride is an unruly tale of everything Gothic, ghoulish and grotesque.”

That unruliness is part of the film’s enduring appeal. While stop-motion has often been overshadowed by the speed and polish of CGI, Burton’s careful construction of miniature worlds reminds viewers that texture, weight and craft can communicate mood and character in ways digital animation rarely replicates.

Fantastic Mr Fox

The sets and puppets for the film were made at Mackinnon and Saunders in Manchester. 126 sets were fabricated for the film. Six differently-sized puppets were made so as to allow for particular shot size framing.

20th Century Fox (2009)

An adaptation of Roald Dahl’s novel of the same name, this stop-motion piece, directed by Wes Anderson, captures a sense of whimsy and strangeness that’s essential to Dahl’s stories.

For Bridget Dash at DNEG, she recalls that: “Everything about stop motion animation appeals to me. That’s why seeing one of my favourite directors, Wes Anderson, bring his unique style and deadpan humour to a Roald Dahl story was something I was determined to love… and it didn't disappoint. Stop motion feels like the medium all of Dahl’s stories were meant for. This film is a perfect match of Wes's tone and technique: the colours are rich and bold, the expressions restrained, and the characters' movements minimal.

"When the action kicks in with sprints, ninja moves and chaotic hijinks, the comedy lands harder because of that stillness. This restraint also makes the film super unique to the medium, as most stop motion films are desperate to be as fluid and perfect as possible to show the amazing skill and effort that the perfection took to achieve. Fantastic Mr. Fox wants to show flaws, including strands of the animal fur that twitch and frenetically move randomly, and I love that they kept these ‘imperfections’ to remind you of the humans who tirelessly made 24 frames per second. I watch it every couple of years, just to be re-inspired by this handcrafted masterpiece.”

Azur & Asmar: The Princes' Quest

Michel Ocelot has devoted much of his work to fairy tale inspired work, and early in his filmography he explored the use paper cut-out animation in his short film The Three Inventors.

Studio Canal (2006)

French filmmaker Michel Ocelot has long been a defining voice in European animation, and Azur & Asmar: The Princes’ Quest showcases his signature visual elegance. Following the international success of Kirikou and the Sorceress, Ocelot returned to the world of fairy tales and folk stories, weaving a narrative that feels timeless while remaining deeply personal.

The story follows two boys, Azur and Asmar, raised as brothers yet separated by circumstance, who embark on parallel quests that ultimately lead to reunion and understanding. Ocelot’s approach emphasizes story over spectacle, letting characters and environment breathe within richly composed frames. The film deliberately avoids photorealism, instead embracing a lush, illustrative style that feels like a storybook in motion. Intricate patterns, vibrant colours, and meticulously designed architecture give each scene a sense of texture and life, balancing narrative clarity with visual poetry.

Animation scholar Dr Chris Holliday notes: “The aesthetic retains an illustrative style that provides the perfect match to the film’s original fairytale narrative.”

That illustrative sensibility is central to the film’s impact. By prioritising design and composition over digital realism, Ocelot ensures that every frame carries both story and emotion. Light, pattern, and perspective work in tandem to guide the eye and deepen immersion, while his character designs remain expressive and readable without breaking the visual harmony of the world.

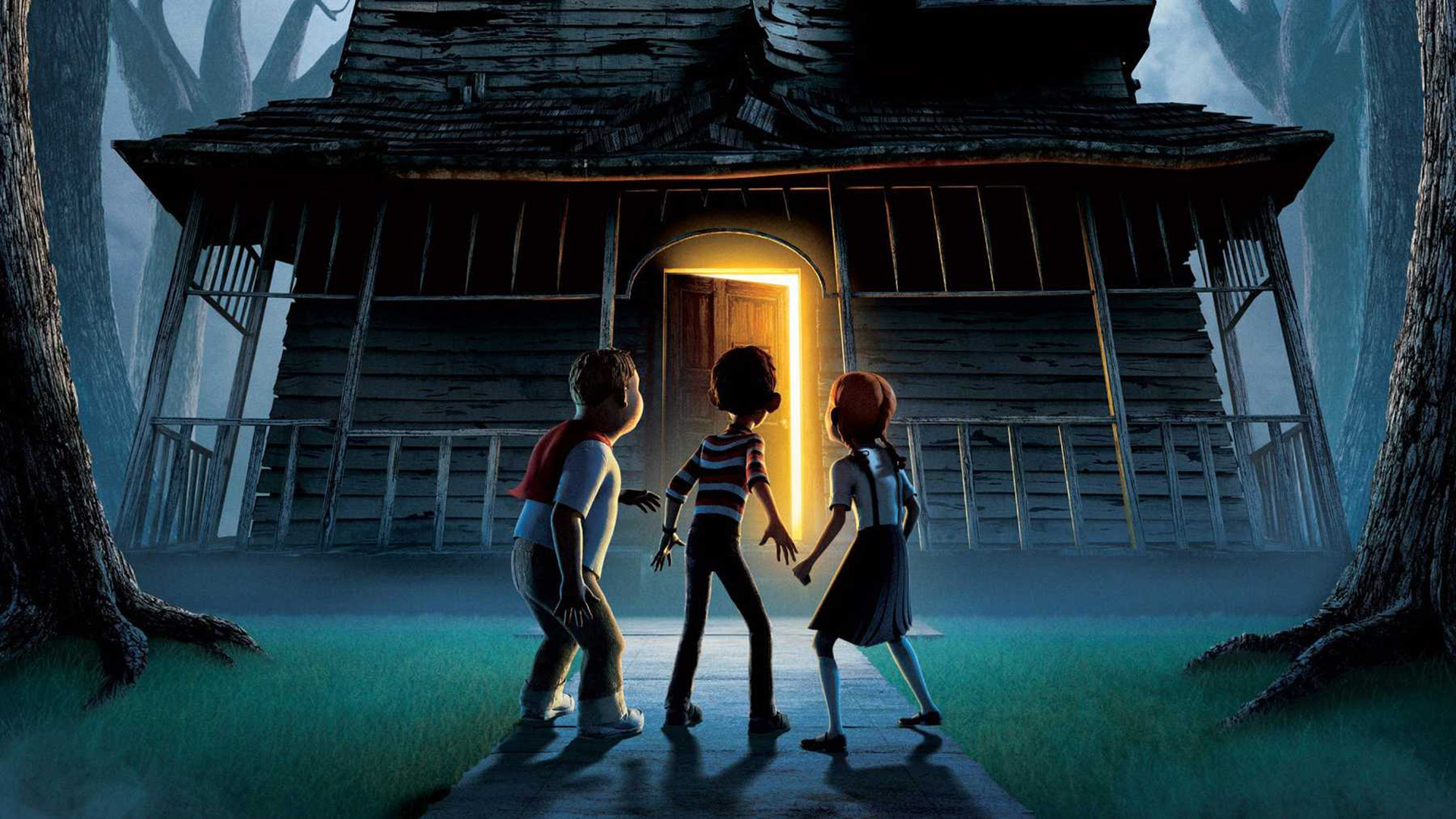

Monster House

Director of Monster House, Gil Kenan, has cited two major animators whose work has been a key influence on his filmmaking; namely, Lotte Reiniger and Jan Svanjmaker.

Columbia Pictures (2006)

Monster House is a standout example of early performance-capture animation in mainstream filmmaking. Blending horror, comedy and adventure, it follows three children who discover that the house across the street is alive; a malevolent presence that threatens anyone who comes near.

The film relied on performance capture for both facial and body animation, allowing the young actors’ expressions, gestures and timing to be faithfully translated into the CGI characters. This gave the children a level of subtlety and realism uncommon in animated features at the time, while stylised designs maintained the exaggerated charm needed for comedic and dramatic beats. Animators then refined the motion capture with hand keyframing, balancing realism with expressive exaggeration.

The house itself is treated as a character, with shifting angles, contorting architecture, and cinematic lighting that heighten tension. Shadows, crumbling walls and dynamic camera moves bring the haunted setting to life, demonstrating how CGI environments can reinforce narrative tone.

Beyond its story, Monster House is historically significant. It helped showcase the potential of performance capture as a hybrid medium, blending live-action expressiveness with animated freedom. This is a technique that has influenced films throughout the decade. Visually striking, emotionally engaging and genuinely funny, Monster House proved that performance capture could serve both storytelling and spectacle, not just technical experimentation.

Ratatouille

The story art process for the film generated about 20,000 drawings to determine the narrative flow of the story.

Ratatouille is one of Pixar’s most beloved films. At its centre is Remy, a rat with a passion for haute cuisine, whose inventiveness enables him to navigate a world stacked against him. His heroism isn’t physical strength or luck, but observation, ingenuity and the courage to pursue excellence despite impossible odds.

Director Brad Bird’s casting of Patton Oswalt perfectly captured that energy. In a National Public Radio interview on 28 June 2007, Bird explained: “He was volatile about food and so passionate and funny about it, you know, it just struck me: ‘That’s the character.’ He’s so volatile, but in a good way. That kind of extreme emotion is perfect for Remy.”

Oswalt’s background in stand-up comedy informs Remy’s performance, giving the character timing, spontaneity and subtle humour that animators translated into physical expression on screen.

Pixar’s commitment to storytelling extends beyond casting. Production manager Nicole Paradis-Grindle observed: “It’s the Pixar way to understand very deeply what you are depicting.”

That philosophy is evident in every frame: the textures of the kitchen, the fluidity of Remy’s movements and the careful staging of each scene communicate character, environment and emotion in tandem. Ratatouille proves that animation can be more than spectacle. When design, performance and philosophy align, even a rat in a Parisian kitchen can feel heroic.

As a final reflection, Dara McGarry, Director of Outreach at DNEG Animation, tells me: “When I first saw Ratatouille in the cinema in 2007, I was delighted by the story of a rat turned chef in the City of Lights. It was warm, funny, charming. But when the Anton Ego Review sequence came up, there was something else. Watching a crusty villain's exterior melt away as he remembered the soothing peasant dish his mother made when he was a boy was the most well-realised piece of animation I had ever seen, and I think I still stand by that today. The resonance of the whip-zoom from the present into his childhood was emotional and tender, as well as the narration over it in which he explains why he's chosen kindness and eschewed the ever-so-easy and fun criticism he often used.”

For a little context, read our Pixar vs DreamWorks feature

Persepolis

A key influence on Persepolis was Maus by Art Spiegel, which remains the only graphic novel to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize.

Persepolis adapts Marjane Satrapi’s acclaimed graphic novels, Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood (2003) and Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return (2004). The film’s visual style mirrors Satrapi’s original comics, using pencil-drawn figures overlaid with black felt tip, creating a stark, hand-drawn 2D aesthetic that feels intimate and immediate. The simplicity of the visuals draws attention to character and narrative, giving weight to the emotional and political nuances of the story.

Art historian Ruth Millington highlights the film’s feminist resonance: “Protest art has a long and significant feminist history, and Iranian artists are using the same savvy tactics as women who have fought battles before them…This new wave of feminist protest art for Iran’s women is also focused on the female body as a disruptive site for change and self-control.”

The film traces Marjane’s journey from a childhood in revolutionary Iran to adolescence in Europe, exploring themes of identity, displacement, and belonging. Production coordinator Sulagna Karmakar reflects on the emotional impact of the restrained animation: “In its stark simplicity, the traditional hand-drawn 2D animation of Persepolis mirrors the visual language and sketchbook-like aesthetics of Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel. The film offers a powerful perspective on the lives of women in the diaspora…nostalgia becomes your exile and belonging a myth. I was genuinely moved by the style and restraint of the animation – it felt raw, revolutionary and deeply personal. Also, PUNK is NOT DEAD, guys!”

The combination of minimalistic design, evocative storytelling, and political awareness gives Persepolis a timeless impact. Its visual simplicity amplifies emotional resonance, while the narrative courageously confronts cultural, social, and gendered issues, proving that animation can be both an intimate personal expression and a powerful medium for social commentary.