2026 is the "toughest Vuelta a España of my life," according to Vuelta director Javier Guilén, and with an all-time maximum of 58,156 metres of vertical climbing, there can be no doubt that, on paper at least, the 81st edition of the Vuelta a España will be one of the most challenging editions ever.

But amidst the seven summit finishes, the near-unprecedented finale in Granada – only once before since the Vuelta's first edition back in 1935 has the race ended so far south of its usual end-point in Madrid – and its third foreign start in as many years in Monaco, some stages stand out as likely being pivotal in the overall outcome.

Here is Cyclingnews' take on what would well be the most important moments of a Vuelta in which Primož Roglič (Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe) is set to fight for a record-breaking fifth ever overall victory – and in the process, perhaps become the second oldest winner of any Grand Tour, too, since Chris Horner in the Vuelta back in 2013.

Tuesday August 25 - Stage 4: an early challenge

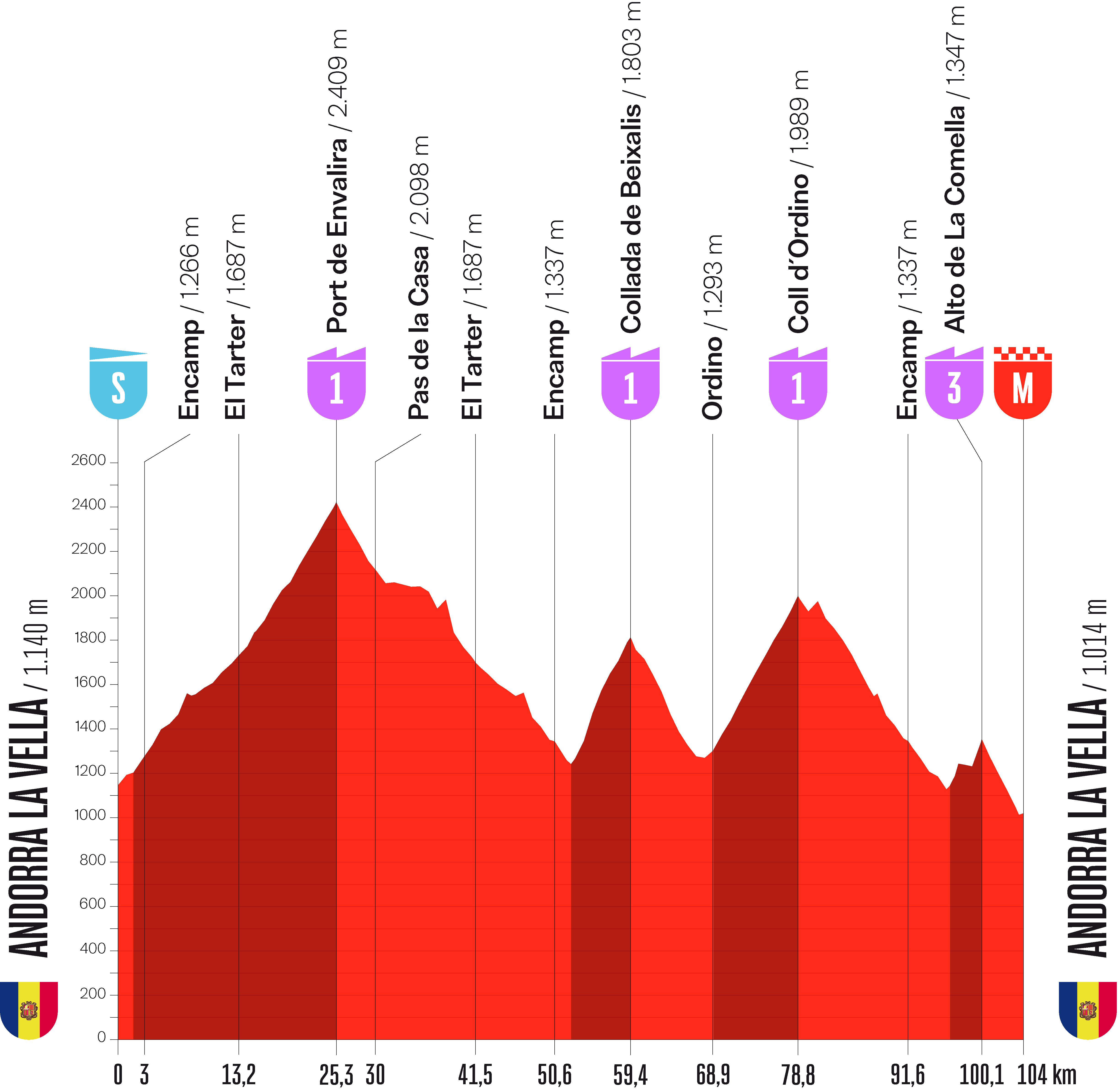

Andorra-Andorra (104km)

This short, punchy run through the mountainous mini-state of Andorra has a very similar feel and position to stage 4 of the 2017 Vuelta a España – and given the high drama that dominated that particular day's racing, that's not a bad thing at all. The build-up is all but identical as well: eight years ago, the Vuelta also began outside Spain, with a team time trial in Nimes in southern France, and just like the race will do in 2026, it then approached the first high mountain stage of the race from the eastern side of the Pyrenees.

We'll already have had some kind of indication of the top riders' state of form in the opening, technically challenging, time trial in Monaco on stage 1, as well as the first summit finish on the Cat.2 Fort de San Romeu, the previous day to the stage in Andorra. But as race route designer Fernando Escartín put it during the 2026 Vuelta's presentation, the most likely outcome on stage 3 at San Romeu will be a mass uphill sprint between 30 or 40 riders, and unless a GC contender is in seriously poor form, few riders will have fallen by the wayside of the overall battle by this point.

Stage 4 should be another, very different, story. Not just because it's got considerably more climbing metres, or because there is a long initial ascent up the Envalira to open up hostilities right from the gun, or even that because it's so short, with three Cat.1 climbs and a Cat.3 in just over 100 kilometres, it means the stage's time cut could well be something for stragglers to worry about. Rather, the constant series of Cat.1 climbs means weaker teams as well as riders will be exposed from the get-go, and the space for recovery between one ascent and the next is very limited.

Last August, a far less challenging opening mountain finale in Andorra on stage 6 already saw riders like Juan Ayuso (UAE Team Emiratex-XRG) lose serious amounts of time. Amongst the weaker GC contenders, this autumn's much harder series of ascents could well exact a far heavier toll.

Just for the record, back in the 2017 Vuelta, the win – also after a downhill drop from the final ascent into the capital Andorra la Vella – went to Vincenzo Nibali. But the key GC ride that day came from Chris Froome, whose trademark windmill accelerations on the lower slopes of the Comella reaped huge benefits.

Nearly all of the GC challengers lost time, while after several years and second places, Froome himself moved into a long-sought leader's jersey, which he then kept all the way to Madrid three weeks later. It's worth noting that the Comella will once again be the last ascent of stage 4 in 2026, too. So anybody wanting to follow Froome's wheeltracks may well use the same climb – or what's come before – to lay down the GC gauntlet for the first time in this year's Vuelta.

Thursday August 27 - Stage 6: onto the gravel

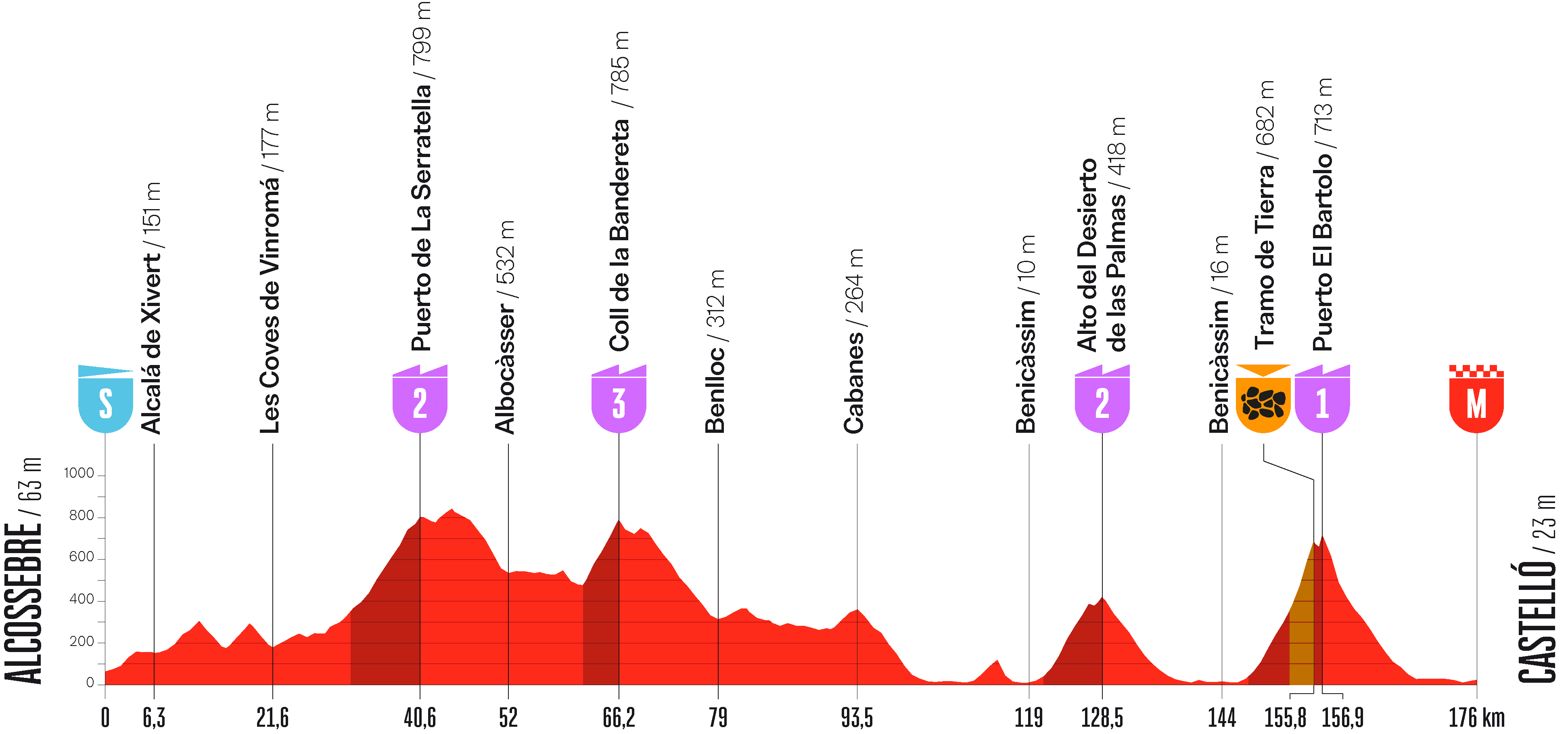

Alcossebre - Castelló 176 kms

It's been a long time coming, but it's finally here. For several years, longstanding TV commentator Pedro Delgado has pleaded with race organisers Unipublic for a gravel stage in the Vuelta, and at long last, on stage 6 in the little-known mountains of northern Valencia, the former double Vuelta a España winner has been granted his wish.

Truth be told, back in 2019, there was a short section of sterrato in the stage won by a certain Tadej Pogačar in the Pyrenees, positioned between the summits of the Cormella and the Cortals d'Encamp. But remarkably for a race that prides itself on innovation, in the Vuelta there has never been anything like the Giro's long excursions through the white roads of Tuscany or through the vineyards of Champagne in the Tour de France. And as for the brief section of off-road in the 2019 Vuelta, barring inconsequential crashes for Miguel Angel López and Primoz Roglič, overall, it had little effect. Stage 6's 3.5 kilometres of gravel, just before the summit of the Cat.1 Puerto El Bartolo, on the other hand, could be very different.

Described as "ambush territory" on the Vuelta's own website, prior to next August, El Bartolo had never featured in any pro races at all, being too hard for the early-season GP Castellon-Ruta de la Cerámica and Classica Camp de Morvedre, which are both held very close by. And as Fernando Ferrari, the editor of specialist cycling website Ciclo21, who has ridden up El Bartolo on several occasions in the past, points out, on a day with a potentially major pitfall late on, that lack of local knowledge could be crucial.

"The fact that the sterrato is so close to the summit could prove very important as well," Ferrari tells Cyclingnews. "If somebody finds themselves in difficulties there, it'll be very hard to make up for lost time on the descent that follows, with just 19 kilometres to go to the finish. Particularly if they don't know the climb, as 99% of them won't."

Put it all together, and stage 6 has all the makings of a classic first-week GC day where you can't win the Vuelta, but you can certainly lose it. That kind of early challenge is hardly new to a race which is traditionally packed with climbs. However, this time, there will be a very unusual – for the Vuelta – gravel-flavoured twist to proceedings.

Saturday 5 September - Stage 14: 'The Angliru of the South'

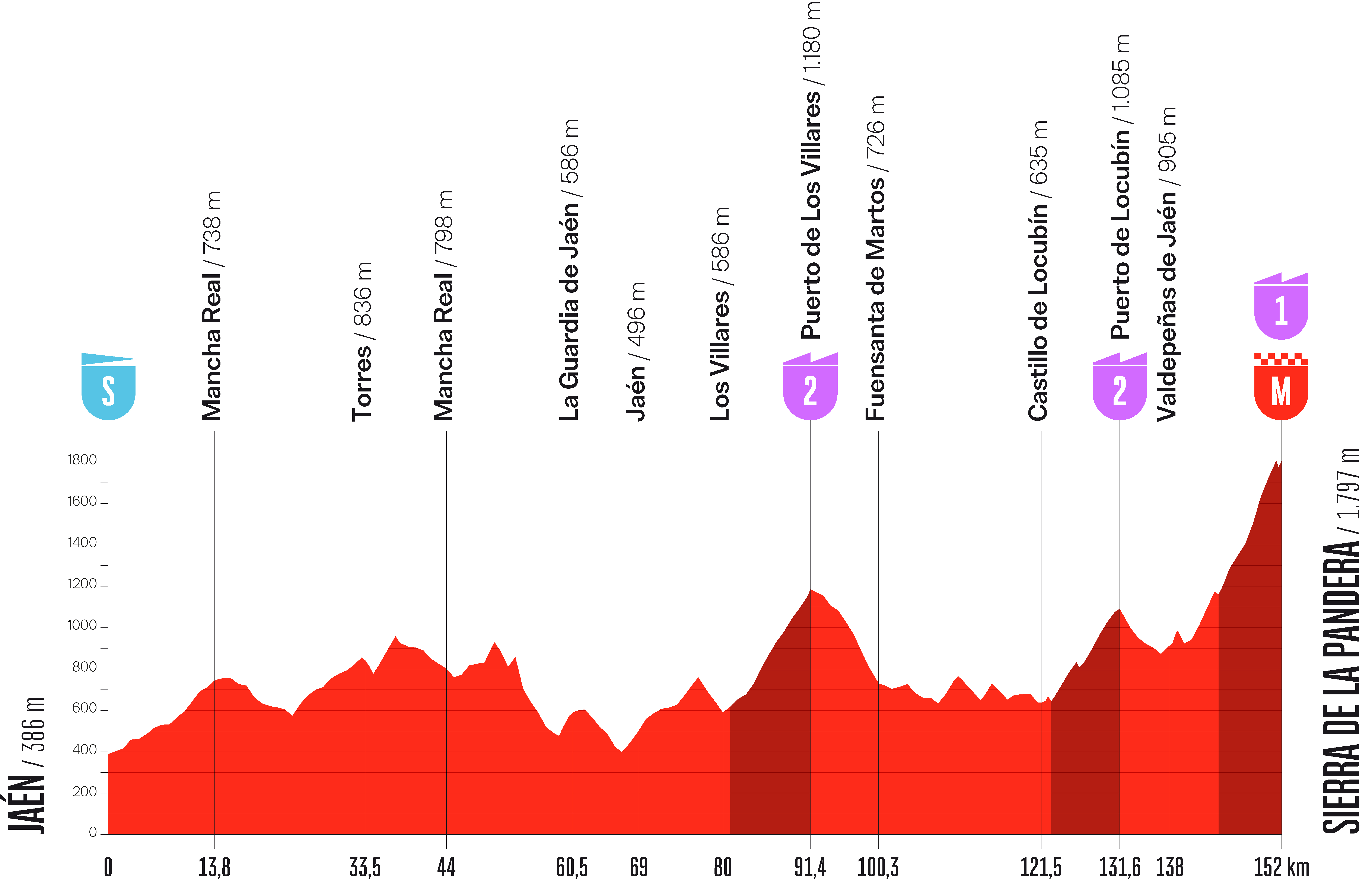

Jaén - Sierra de la Pandera 152 kms

Some local fans have dubbed the climb of Sierra de la Pandera, an agonisingly steep, poorly surfaced mountain road to nowhere, running deep through the sea of olive groves that makes up the province of Jaén, as the 'Angliru of the South'.

The reality of one of the Vuelta's newest climbs, first introduced in 2002, is not quite as spectacular as the monster Asturian ascent some 1,000 kilometres further north. But what's also undeniable is that whenever the Vuelta's gone up the Sierra de la Pandera in the past – and we're now at six times and counting – it almost invariably has a big impact on the overall classification.

Back in 2022, for example, Primož Roglič delivered a powerful blow to Remco Evenepoel's overall lead on the Pandera. His attack left the Belgian severely rattled, and there's no knowing that if Roglič hadn't crashed out a few days later, the bones of a minute that he claimed on Evenepoel that day could have had far bigger consequences than just one stage of thrilling racing.

The Pandera certainly can't be underrated, then, partly because even if the Vuelta organisers themselves regularly claim it's only eight kilometres long, in reality the full distance of climbing is almost three times that. From the point where the road first begins to rise in the tiny town of Los Villares, right the way to the now-defunct military base at the top, there are actually 23 kilometres of uphill.

The first 16km are on relatively straightforward roads with a maximum gradient of 8%. But by the time the riders swing onto the final 'climb proper' of eight kilometres with slopes that max out at 21%, they'll already be feeling under considerable pressure from what's come before.

That's not even to take into consideration the 120 or so kilometres that precede the Sierra de la Pandera. Nominally only containing two Cat.2 ascents, the Puerto de los Villares and the Castillo de Locubin, in fact, the roads through the remoter areas of one of Spain's least populated provinces rarely offer any respite from constant, draggy rises, switchback descents and some notoriously technical bends. All in most likely 40-degree heat, or higher.

Ironically enough, the first two-thirds of the Sierra de la Pandera, which include a lengthy section of false flat after some ten kilometres, are amongst some of the best surfaced in the region. That is in stark contrast to the winding, narrow, goat-track of an ascent that follows, picking its way through sunparched sierras with a very steep first kilometre of between 10% and 12%, then another two kilometres mid-way up of even stiffer average gradients.

Could the Sierra de la Pandera even act as kingmaker for the Vuelta? Given what's left to race – a very tough time trial and two major mountain stages at the end of the third week – you can't say that. But as one of the key obstacles to anybody wanting to wear the leader's red jersey for good on the final day in Granada, the Sierra de la Pandera certainly can't be faulted. Just ask Remco Evenepoel.

Thursday 10 September - Stage 18: The time triallists' revenge

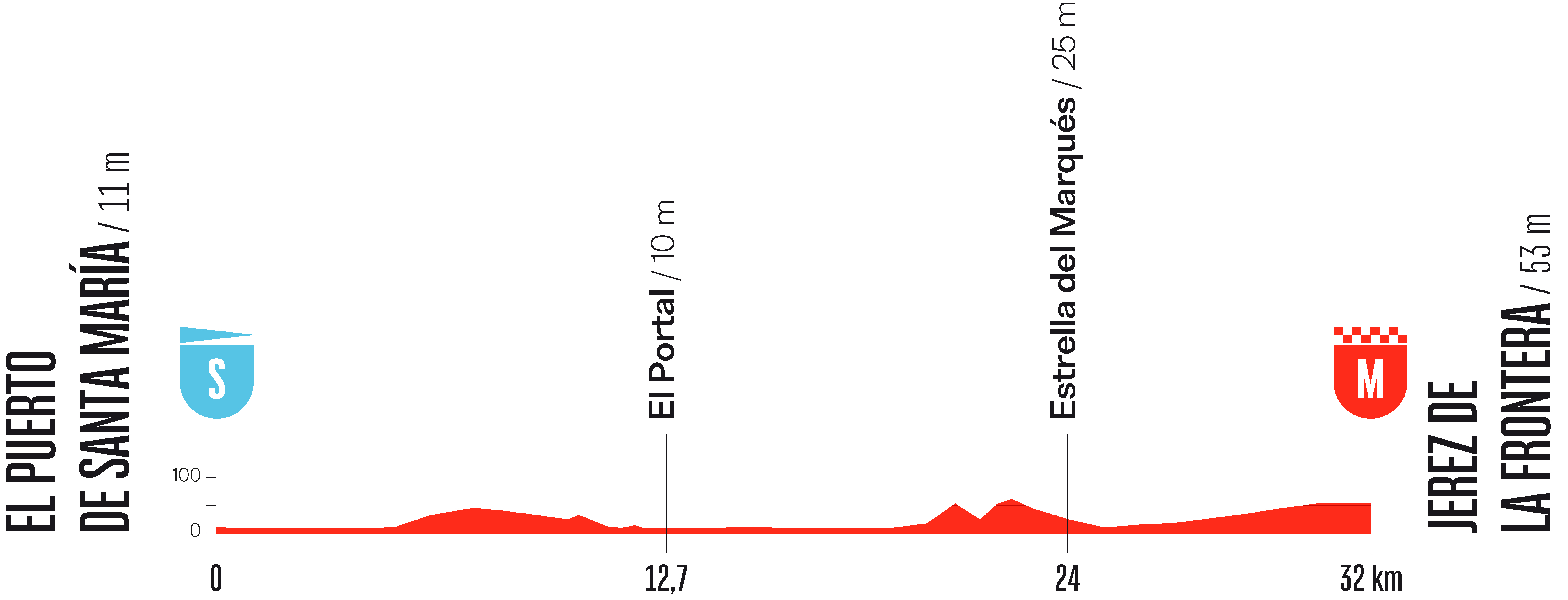

El Puerto de Santa María - Jerez de La Frontera: 32 kms ITT

Last autumn, when the 2025 Vuelta a España route was revealed, the first thing we all noticed after the bizarre (but surprisingly successful) first four days in Italy and France was the sheer volume of the mountain stages in the north and east of Spain. However, it also transpired that on stage 18 of the Vuelta, rather like the lone Gaulish village of Asterix and Obelix surrounded by legions of Romans in the French cartoon series, Vuelta organisers Unipublic wanted to put the ball back in the time triallists' court with a solitary but striking 33-kilometre race against the clock. Just to rub in their point, the time trial was going to be on pancake flat roads, too.

As is well known, Unipublic's attempt to produce yet another decisive race against the clock in a city dubbed the Vuelta's unofficial capital of time trialling – there have been so many there in the past – failed miserably, and through no fault of their own. Threats of disruption by pro-Palestine protests led to a radical reduction in the time trial length, from 27 kilometres to 12.2, and although João Almeida (UAE Team Emirates) produced a strong effort to overhaul Jonas Vingegaard, his net gains of 11 seconds were minimal by anyone's standards. At a distance like that, though, short of falling into the wizard's cauldron of magic potion as a baby like Obelix in the cartoon books, Almeida could hardly have done any better.

Stage 18 of the Vuelta in the flatlands of Jerez in SE Andalusia could produce a very different story. Placed at an identical point in the race as last year's drastically curtailed time trial, 32 kilometres of almost completed flat is more than enough for a specialist against the clock to place an important downpayment on final success. Furthermore, the wind in the area is usually far stronger even than in Valladolid, given the proximity of much of the exposed course to the open Atlantic coastline and could cause even bigger gaps than expected.

It's true that in the third week, the differences between the top racers in a time trial are generally less than those held in the first week when riders are fresher. But in such a tough Vuelta a España and at the tail end of a long season, on such a difficult course, climbers could well end up cracking all the same. After all, to give one example, this was exactly what happened in a third week TT in 2010 in (where else?) the region of Valladolid, when 'Purito' Rodriguez, so talented at blasting the opposition off his wheel on the climbs, lost the race lead for good in a time trial to eventual overall winner Vincenzo Nibali.

"We'll likely see two battles on that day," Delgado pointed out, "one for the stage with a specialist like Filippo Ganna, and the other for the overall." Quite whether the 'Gaulish' time triallists can beat the legions of 'Roman' climbers remains to be seen. But like Asterix and Obelix, they'll certainly provide some solid entertainment along the way.

Saturday 12 September - Stage 20: the final showdown

La Herrada - Collado del Alguacil: 187kms

"If I was the race leader, knowing what's coming up that day, I wouldn't be sleeping easy no matter how big an advantage I'd got," is how Luis Angel Maté, a former pro from Andalusia who lived locally for several years, describes the Collado del Alguacil – the final ascent of the Vuelta a España, and arguably one of the very hardest.

Part of the vast network of climbs that criss-cross the southern side of the vast mountain range of Sierra Nevada, the Collado del Alguacil comes at the end of what is undoubtedly the toughest day of the entire Vuelta a España. As Maté points out, with more than 5,000 metres of climbing in total, when preceded by the almost equally hard Alto de Hazallanas – twice – and the Alto del Purche, this last high mountains stage is easily on a par with any of the biggest challenges of the Tour or Giro. Then, when combined with searing southern Spanish summer heat, the toll of three weeks' hard racing and its position in the race as the last chance saloon for any rider to turn the tables, Maté reckons there's every chance of a long-distance GC attack.

"It's very much a stage for the Vuelta finale," argues 2006 Tour de France winner Oscar Pereiro during the Vuelta presentation, where he was one of the commentators for Spanish television's RTVE. "This is where we'll get a last verdict for sure. We already saw a couple of years ago [2024] when there was a stage over many of these climbs in the Vuelta and Adam Yates won, the race was blown apart and the riders came across the line in ones and twos."

Hazallanas and El Purche have witnessed some spellbinding Vuelta climbing battles in the past, and Maté believes next September they will automatically ensure the race has broken apart well before the final Alto del Alguacil climb. "It's got a very technical, narrow approach through the village of Güejar Sierra at its foot," he tells Cyclingnews, "but the previous climbs, as well as the gradual ascent to the start of the climb 'proper' means you won't have more than a handful of riders in the lead by that point at most."

As for the actual ascent, he says, "it's around nine kilometres long but at a constant 10% or so as an average. The first 200 metres are particularly difficult, with slopes of around 20% and then a short breathing space, but the hardest part is right at the top, with a couple of really tough, never-ending hairpins as well."

Although the road surface itself, barring one very short unsurfaced section, is pretty good and not overly narrow – "the team cars will have a problem getting past," he says – the last segment holds another unexpected challenge: the wind.

"By then it's open and really exposed and you can essentially have wind in two directions, head or tail, never cross. So it could play a big part in how that last kilometre plays out."

"That last kilometre is really hard, anyway, easily above 10%, two tough bends and the most difficult part of all is right at the top."

Whilst whoever is wearing red at the top of El Alguacil can be almost certain of overall victory, Maté warns that the last stage, with multiple tough ascents of a short but technical ascent to the Alhambra, could yet produce surprises. But Pereiro points out that for all the riders, the degree of popular support they will encounter can at least provide some motivation for one final throw of the dice, come what may.

"The fanbase in Andalusia isn't one of Spain's most famous for supporting cycling," Pereiro says, "but whenever I got there, I'm always surprised by how big the public turnouts are for races, in Granada in particular. Whatever's going on in the race by then, for sure it'll be a great finish to it all."