The world’s major cities are enduring a quarter more very hot days each year than three decades ago, new research says.

The 40 most-populous capitals, and three other politically significant cities, experience 26 per cent more days over 35C now than in the 1990s, according to an analysis by the International Institute for Environment and Development.

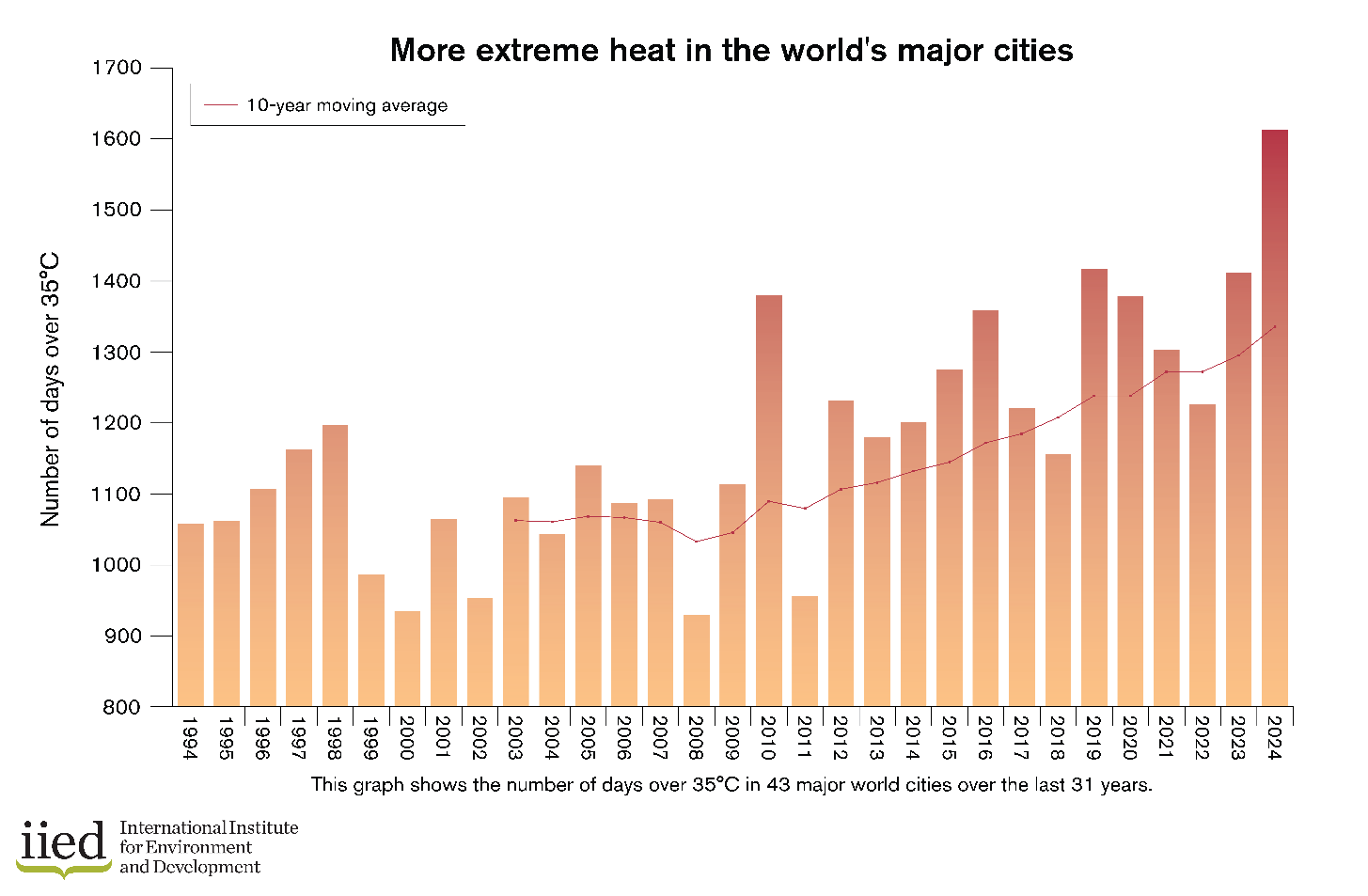

Between 1994 and 2003, these cities averaged 1,062 days of extreme heat annually. That figure climbed to 1,335 days between 2015 and 2024, with 2024 recording the highest tally of all – 1,612 days across the 43 cities.

The top three years for extreme heat all came in the recent past: 2024, 2023 and 2019.

Nine cities, including Washington, Tokyo, Cairo and Johannesburg, reported record numbers of very hot days last year.

The researchers say the findings show there is an urgent need to adapt urban environments to rising temperatures while countries also cut greenhouse gas emissions, with the next round of national climate pledges due ahead of the Cop30 climate summit in Brazil.

“Global temperatures are rising faster than governments probably expected,” Anna Walnycki of IIED said, “and definitely faster than they seem to be reacting. Failing to adapt will condemn millions of city dwellers to increasingly uncomfortable and even dangerous conditions because of the urban heat island effect.”

The analysis shows more striking shifts in cities across Africa, Asia and Latin America as population growth and weaker infrastructure leave people especially vulnerable.

South Africa’s Pretoria now averages 11 days above 35C every year, up from just three in the 1990s.

Johannesburg recorded only three such days between 1994 and 2021, but 26 since 2022.

In Brazil, Brasilia registered only three days above 35C in the 1990s compared to 40 in the past decade. Even a typically cooler São Paulo hit 120 days above 30C last year, the most in the study period.

In Southeast Asia, Hanoi’s 10-year average of very hot days nearly doubled while Kuala Lumpur’s almost tripled.

Heat is also rising across Europe, which experienced a blistering summer in 2024. Rome’s average number of 35C days has more than doubled since the 1990s, and Madrid’s has climbed from 25 to 47 a year.

Scientists warn that extreme heat can be deadly, particularly for children, older people and those in outdoor or manual jobs.

Sustained high temperatures inside poorly insulated homes are also a problem in both rich and poor countries.

Globally, around a third of urban residents live in slums or informal settlements, often in poorly built housing with limited ventilation, the study notes.

“The poorest people will likely suffer the most whether they’re in London, Luanda or Lima,” Dr Walnycki said, “but the impacts will be significantly worse in low-income or unplanned communities in the Global South.”

The researchers suggest cities should expand shade cover, improve insulation and ventilation in buildings, and ensure new developments are designed for a warming world.

“Many of us know what it’s like to lie awake at night, dripping sweat during a heatwave,” Dr Walnycki said.

“This isn’t a problem we can simply air-condition our way out of. Fixing it requires comprehensive changes to how neighbourhoods and buildings are designed, and bringing nature back into our cities.”

The 43 cities covered in the latest study are home to nearly 470 million people – a figure expected to increase sharply in the coming decades. Without investment in adaptation, the researchers warn, the toll of rising heat will only worsen.