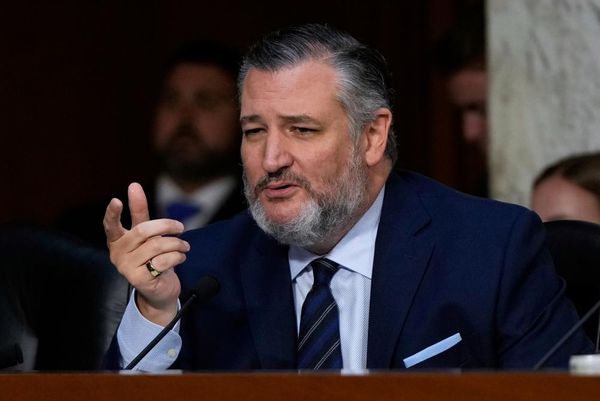

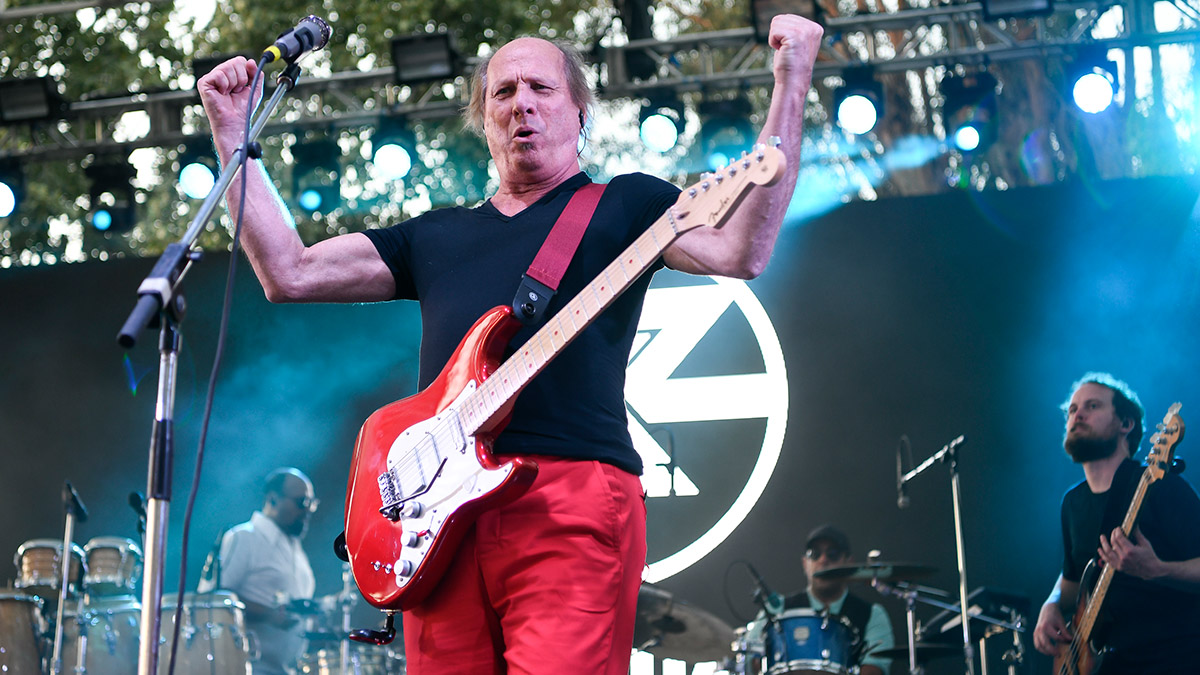

Lots of guitar nerds would consider Adrian Belew a virtuoso, and it’s hard to argue against them. But he’s really a virtuoso of sound and form more than show-off technique.

As a one-time member of prog rock institution King Crimson, a solo artist balancing Beatles-like ear worms and outré studio craft, and an A-list hired gun for legends like Talking Heads, Frank Zappa and David Bowie, he’s created his own language on the guitar. Literally no-one else could sound like him if they wanted to – partly because his skill set is so distinctive, partly because he approaches effects pedals like a painter would colors.

For Belew, head-turning gigs begat head-turning gigs in the late Seventies and early Eighties: In a legendary three-year studio streak (not even mentioning his stage work), he appeared on Zappa’s Sheik Yerbouti, David Bowie’s Stage and Lodger and Talking Heads’ Remain in Light – solidifying his joyously wacky approach to sound design and an aggressive rhythmic energy that drew on his background as a drummer.

In the reformed Crimson, he teamed with bandmate Robert Fripp to create a startling guitar style drawing, at various points, from the glow of New Wave, the bombastic snarl of metal, and the interlocking principles of gamelan. And he’s continued to innovate with each band, album, and one-off collaboration.

The beauty – and irony – of Belew is that his sound is in constant flux, but few guitarists are so easily identifiable. No list could even scratch the surface, but below we round up 10 of his definitive guitar moments.

10. Young Lions – (Adrian Belew, from 1990’s Young Lions)

Belew’s fifth solo album is a bit of a grab-bag, source-wise – compiling covers of The Traveling Wilburys (Not Alone Anymore) and, technically, himself (King Crimson’s Heartbeat); two link-ups with Bowie (Pretty Pink Rose and Gunman); and a track that samples radio evangelist Prophet Omega (I Am What I Am).

You’d think the vibe would be chaotic, but Young Lions could be his most consistently melodic work, kicking off with the sharpest pop song in his catalog, the chugging title track.

The primary guitar part is more subtle and funky than Crimson fans may have expected, showcasing his knack for Beatles-y chord changes. But there’s also some good old-fashioned Belew animal noises (elephants and lions, at the very least), matching the mood of this “hot tribal night.”

9. This Is What I Believe In – (Adrian Belew, from 1992’s Inner Revolution)

Belew opens this introspective rocker, a sort of bluesier cousin of King Crimson’s Neal and Jack and Me, with several sweetly sung sentiments: “Hold tight to your faith / Don’t let nobody make you jaded / Your love is precious / Give it to somebody who deserves it / This is what I believe in / Hold tight to yourself / Don’t let nobody give you hell.”

But the song grows darker as it grinds on, with Belew warning of a “dangerous,” cannibalistic world “full of homicidals and terrorists.” Still, by the song’s conclusion, you’re left with a warm sense of optimism – urged on by some of his most colorful guitar work, including an instrumental bridge full of violin-like churning and a solo that recalls the soulfulness of Stevie Wonder’s harmonica.

8. The Momur – (Adrian Belew, from 1982’s Lone Rhino)

Falling somewhere between palm-muted power-pop and ragged New Wave punk, The Momur is Belew at peak silliness. Between swarming feedback, atonal fills, and an impressively sustained solo, the guitarist channels the absurdity of Zappa, sharing a B-movie-type tale his old pal and musical mentor might have appreciated.

Here’s the plot: The previous night, the protagonist’s wife turned into a monster, backed him into a corner, tried to kill him with a broom (seems difficult, doesn’t it?), smashed his favorite guitar, and even danced on the wreckage. (The seemingly random title was a family joke: Belew’s daughter Audie, then only three, used to babble the word “momur” instead of “monster” when she got scared by something.)

“It’s from back in the day when I was still trying to be funny in my songs, which came from my work with Frank Zappa,” Belew explained to Innerviews in 2022. But that tip of the cap seems to extend even beyond the words – musically, it’s easy to picture The Momur as part of a late-Seventies Zappa album like Sheik Yerbouti.

7. Tango Zebra – (Adrian Belew, from 1986’s Desire Caught by the Tail)

On a purely tonal level, Belew is probably best known for being animalistic. Literally – he once displayed his gift for beastly mimicry during a Japanese TV commercial, accurately channeling chickens, cats and elephants.

But his guitars, when prompted, can also speak the language of other instruments, as showcased through the experimental folk orchestrations of Tango Zebra. It’s a journey song of the highest magnitude, opening with the twang of resonators and gradually growing more synthetic – the result lands somewhere between jazz, bluegrass and avant-rock.

It’s unlike anything else in his catalog, not least because of the unique arrangement, inspired partly by George Gershwin. “[T]hat’s how I approached it,” Belew told Music Technology in 1987, “as though there really were members in this orchestra and I had to produce for their instruments.” The most blatantly orchestral touch: a section of electric guitars that sound uncannily like woodwinds. Except that they don’t quite – like basically every other Belew tone, it sounds uniquely his.

6. e2 – (Adrian Belew, from 2009’s e)

By the late 2000s, Belew had collaborated with the elite of prog and art-rock – he could pretty much record with anyone, forming whatever outlandish supergroup he pleased.

Most people in this exalted position wouldn’t start a brand new band from scratch – in this case, the Adrian Belew Power Trio – with a pair of relatively unknown young adults. But brother-sister rhythm section Julie Slick (bass) and Eric Slick (drums) brought a renewed vitality and edge to Belew’s music, best displayed on a knotty five-part suite dubbed e.

It would be cheating to pick the full, 42-minute piece (the swaggering live favorite b deserves an honorable mention), so let’s turn to the eight-minute finale, e2, in which Belew unfurls chromatic runs and unnerving harmonies over Julie’s staccato bass riffs. As with many of his tunes, this one takes on a new intensity in concert, as Belew builds mountains of overdubs with a looper pedal.

5. Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On) – (Talking Heads, from 1980’s Remain in Light)

Talking Heads didn’t exactly need any guest players on their fourth LP – and they certainly didn’t need a gravity-bending show-stopper like Belew on the densely arranged funk-rock opener, Born Under Punches (The Heat Goes On).

The song is stuffed to the gills with overdubs, as electronic bloops, bass riffs, and backing vocals pile into a polyrhythmic groove that borrows its all-hands-on-deck heft from African music. And that’s before even mentioning Heads frontman David Byrne, whose raving lands somewhere between cryptic paranoia and plain gibberish (“Take a look at these hands / The hand speaks, the hand of a government man / Well, I’m a tumbler / Born under punches / I’m so thin”).

In summary, there’s already a lot to unpack. But then Belew, who’d later join the band on the Remain in Light tour, added a magic dash of secret sauce: a long stretch of guitar playing that sounds like an ancient, defective modem booting up on an alien planet.

“I recorded a guitar solo and then ran it through an expensive piece of studio gear called a Lexicon Prime Time,” Belew wrote on Facebook, “which allowed me to alter the [bandwidth] of the sound while capturing quick little loops I could fool with.”

4. Three of a Perfect Pair – (King Crimson, from 1984’s Three of a Perfect Pair)

Throughout the Eighties, King Crimson invented their own language within progressive rock – their best songs were both snappy and strange.

By the time the classic quartet lineup reached Three of a Perfect Pair, their last of an early-decade trilogy, those extreme sensibilities seemed to be diverging: “The album presents two distinct sides of the band’s personality, which has caused at least as much confusion for the group as it has the public and the industry,” Fripp wrote in the album’s press release. “The left side is accessible, the right side excessive.”

Kicking off the former half is the classic title track, which is – let’s be honest – still pretty damn unorthodox for any band not named King Crimson. Belew and Fripp revive their now-standard interlocking guitars for the verses, grounded by the polyrhythmic force of bassist Tony Levin’s jumpy low-end and Bill Bruford’s restrained acoustic drumming.

It’s already a highlight of their entire Eighties run, but that’s before you dig into Belew’s sputtering guitar-synth solo, assembled, like Born Under Punches, through studio doctoring with the Lexicon Prime Time.

3. Level Five – (King Crimson, from 2003’s The Power to Believe)

During a run of dates with heavy prog masters (and King Crimson disciplines) Tool way back in 2001, the prog legends road-tested fresh material that wound up on their 13th and final studio album, The Power to Believe.

Tool’s influence seemingly rubbed off: The music is darker and more metallic than anything Crimson had released since 1974’s Red. (The album’s working title was, fittingly, Nuovo Metal.) There’s no better example than opener Level Five, a piece almost frightening in its attack.

The track, originally described as the fifth installment of their Larks Tongues in Aspic series, offers plenty of fireworks from both Belew and Fripp, as both players react to the sputtering, glitchy electro-acoustic drumming of Pat Mastelotto. But Belew’s MVP moment arrives after the five-minute mark, when he breaks into a torrent of high-octave squeals and dazzling dives.

2. Frame by Frame – (King Crimson, from 1981’s Discipline)

If Elephant Talk is the playful centerpiece of Discipline, Frame by Frame is the album’s serious, beard-stroking prog moment – the yin to that song’s yang. (Ironically, the lyrics originated from a sort of in-joke between Belew and Levin, the band’s other American member, about the analytical side of their studious British bandmates.)

The track is quintessential Eighties Crim, built around a complex twin-guitar pattern in 78 that drifts apart before locking back into place.

But even if Fripp and Belew could meld into each other’s styles, they never tried to hide their differences: Frame by Frame opens with a disorienting instrumental section with the two playing off each other brilliantly – Fripp overcome in a flurry of rapid-fire picking, Belew strangling his strings into chunky rhythms and whammy bar wildness. (To fully appreciate the latter’s work on this behemoth, check out the live version from the Neal and Jack and Me concert DVD.)

1. Elephant Talk – (King Crimson, from 1981’s Discipline)

It may be the obvious choice, of course, but… come on! Elephant Talk has everything you could possibly want from Belew: the elite musicianship, the raw creativity, the sense of child-like wonder, the boatload of guitar effects. (The one thing it doesn’t feature is the man’s underrated singing – this one’s basically spoken.)

The song bloomed from a funky guitar riff that Belew eventually suggested that Levin refine on his Chapman Stick – and from there, the former was free to go nuts with the pedals. It’s a tour de force: woozy dives, static-wrapped rhythms, harmonic pings and, most crucially, a flange-and-fuzz combo that sounds unmistakably like the roar of a freaking elephant.

Belew’s lyrics add another layer of gleeful mania, moving alphabetically to list the various kinds of human speech. (Best part: “These are words with a ‘d’ this time!”) Since the words didn’t rhyme, he felt no need to sing in the traditional sense, instead leaning into a bizarre holler. Luckily he made it up to the letter “E,” allowing him to connect the dots between elephant sounds and, well, whatever it was Elephant Talk actually meant.