Lady Godiva – an icon of protest, myth and sensual defiance – has galloped through centuries of our cultural imagination. She is most widely known for the legend of her naked horse ride, in which she supposedly rode through the city of Coventry, England, in nothing but her cascading hair.

According to the popular tale, Godiva pleaded with her husband, Lord Leofric of Mercia, to lift an oppressive tax that threatened to impoverish the people of Coventry.

Leofric issued a provocative challenge: he would only revoke the tax if she rode unclothed through the town. In a gesture of defiance and compassion, she undertook the ride.

The townspeople, in respect, shuttered their windows, except for one man named Tom, who was struck blind. This is where we get the phrase “peeping Tom”. Moved by her courage, Leofric kept his word and abolished the tax – or so the story goes.

While many historians believe this naked ride never actually took place, Godiva, the 11th century noblewoman, was real – as is her enduring influence.

Godiva has been endlessly remixed, from appearances in literature, to art, to music, to comics, and even chocolate.

Although Godiva has historically been objectified, her legacy is ever-evolving. Through parades and processions, political protest, and philanthropic campaigns, fans and activists alike have transformed Godiva into a symbol of resistance.

The lady behind the legend

Countess Godgyfu (meaning “God’s gift” in Old English) was born around 990 CE and died sometime after 1066. She was the only female Anglo-Saxon landowner listed as “tenant-in-chief” in the Domesday book.

According to historian Daniel Donoghue, this implies an exceptionally high noble status and independent authority, suggesting Godiva held her estate by birth, rather than through marriage.

She married Lord Leofric of Mercia, a powerful Saxon military leader. Her Christian piety and philanthropic influence are credited with inspiring the foundation of the monastic site of Coventry’s original cathedral.

Her will included a string of prayer beads – an early reference to the rosary.

Fanning herstory

The legend of the naked horse ride draws from older mythological traditions.

In his book The White Goddess (1948), English writer Robert Graves interprets Godiva as a medieval manifestation of a pagan goddess. Her symbolic nudity and ritualistic ride echo fertility rites and goddess worship.

Like many medieval legends of pagan or folkloric origin, it was transformed into a Christian narrative over time, intertwined with the real history of the philanthropic Countess Godgyfu.

Fandom offers a compelling lens through which to view Godiva, and the ways her story continues to resonate in contemporary culture.

In the 2016 book I’m Buffy and You’re History, author Patricia Pender explores how fandom enables playful and subversive representations of femininity. For instance, Buffy – a female character who nonchalantly slayed vampires, rather than running screaming – subverted expectations. By riding naked, Godiva, too, subverts expectations.

At the same time, feminist scholars have critiqued representations of nude women in culture and the arts as catering to the male gaze, rather than being subversive. Researcher Melisa Yilmaz argues Godiva has been moulded into a passive symbol of erotic spectacle, rather than female empowerment.

Godiva’s image is also commodified globally, most notably by the Godiva chocolatier.

Yet, reinterpretations of her legend through centuries of fandom offer a counter-narrative.

Women who refuse to be shamed

Godiva became very popular in the 19th century. She is featured in a poem by Alfred Tennyson, in pre-Raphaelite paintings, in works by Salvador Dali, and even in a statuette gifted to Prince Albert by Queen Victoria.

She gained renewed popularity through women writers, activists and suffragists. For instance, in the 1870s, British political activist Harriet Martineau told women who feared exposure and condemnation for taking up controversial causes to “think of the Lady Godiva”.

Once such cause at the time was the campaign against the Contagious Diseases Act. This act, which applied only to women, meant police could arrest women assumed to be prostitutes and have them medically examined.

Similarly, social reformist Josephine Butler entitled her 1888 political play The New Godiva. In it, she wrote about the need for a female campaigner to

compare her[self] to Godiva, stripping herself bare of the very vesture of her soul […] exposing herself to something worse than physical torture.

Radical reclamation

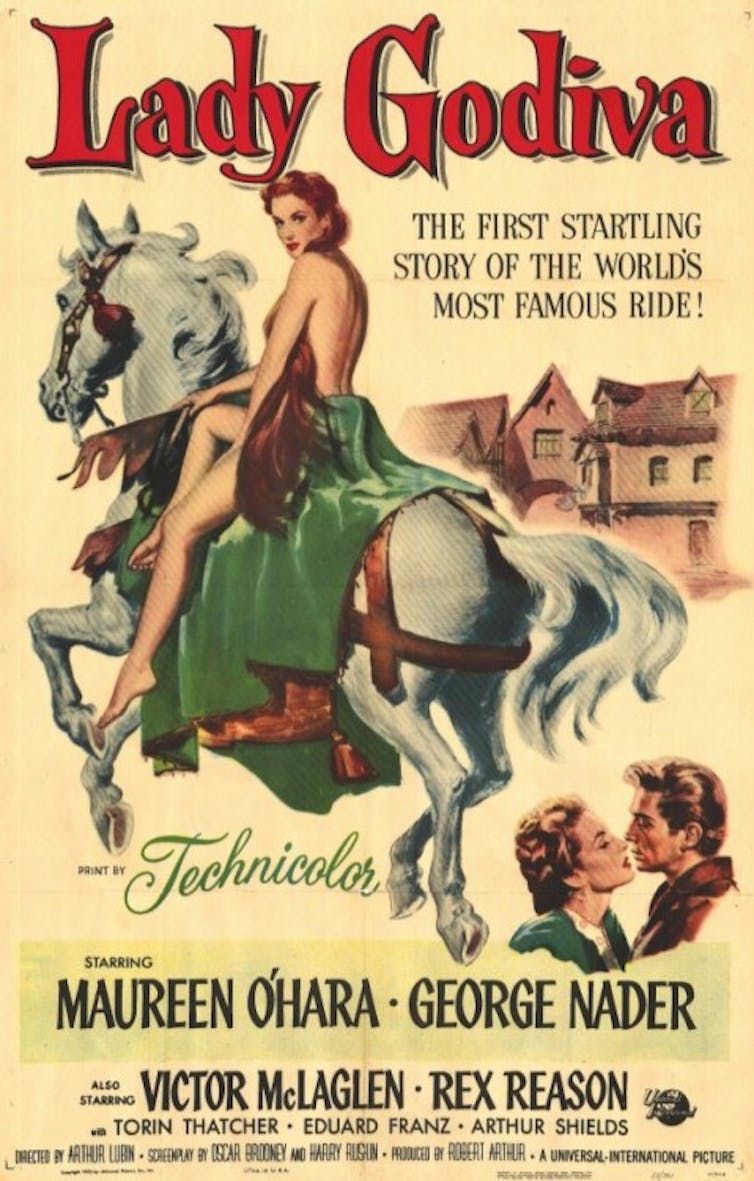

Lady Godiva is widely referenced in film and TV. She was the subject of the historical 1955 film Lady Godiva of Coventry, starring Hollywood starlet Maureen O’Hara, and has appeared as a character in shows such as Charmed (1998–2006) and Fantasy Island (1977–84).

Contemporary women authors have also offered up various twists of Godiva’s tale. In Judith Halberstam’s young adult novel Blue Sky Freedom (1990), for example, Godiva is the name given to an anti-apartheid resistance leader.

In the DC Comics, the character Godiva is a beautiful woman with powerful hair she can control to her advantage.

She shows up in music, too. The cover of Beyonce’s 2022 album, Renaissance, shows the singer astride a holographic horse in a seemingly Godiva-inspired pose – boldly facing the camera.

In Queen’s song Don’t Stop Me Now, Lady Godiva is likened to a racing car:

I’m a racing car, passing by like Lady Godiva

I’m gonna go, go, go, there’s no stopping me.

Coventry city has had an official Lady Godiva, Pru Porretta, for more than three decades. Porretta’s role involves a range of community and philanthropic work.

Godiva’s legacy in Coventry continues through archaeological sites such as the Coventry Cathedral, guided Godiva-themed walks, and public celebrations including the annual three-day Godiva Festival.

Elizabeth Reid Boyd does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.