Croke Park may be hosting Oasis in August, but it is Omni Park shopping centre in the nearby Dublin suburb of Santry that’s having its rock’n’roll moment right now. It comes courtesy of the video for “Euro-Country”, the new single from Irish country-pop singer Ciara Mary-Alice Thompson, aka CMAT, in which the unremarkable complex serves as a warning against the dangers of unfettered greed.

“All the big boys, all the Berties/ All the envelopes, yeah they hurt me,” sings Thompson as she twirls through the two-storey building, home to an adjoining 11-screen cinema and Lidl supermarket. She isn’t railing against the Omni itself – the shopping centre, which underwent a major expansion at the height of the pre-crash Irish property boom, is an apt stand-in for the bonfire of turbocharged capitalism that swept Ireland during those feverish years, its flames fanned by populist head of government Bertie Ahern. Just so nobody misses the point, she is also wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with “Bertie”.

Were CMAT a UK artist, none of this would be remarkable. British songwriters have been taking potshots at prime ministers for decades, from The Beat (“Stand Down Margaret”) to Stormzy (“F*** the government and f*** Boris”). From an Irish musician, however, lyrics fired at a prominent and still-living politician is something new, exciting, and daring. And Thompson isn’t alone. Amid a housing meltdown, a soaring cost of living crisis, and the march of the far right, Irish music is finding its political voice in a way quite distinct from previous generations. Artists are calling out politicians and parties by name and taking on the racists – a radical break with Irish rock’s history of grand but often empty gesturing (see U2, etc).

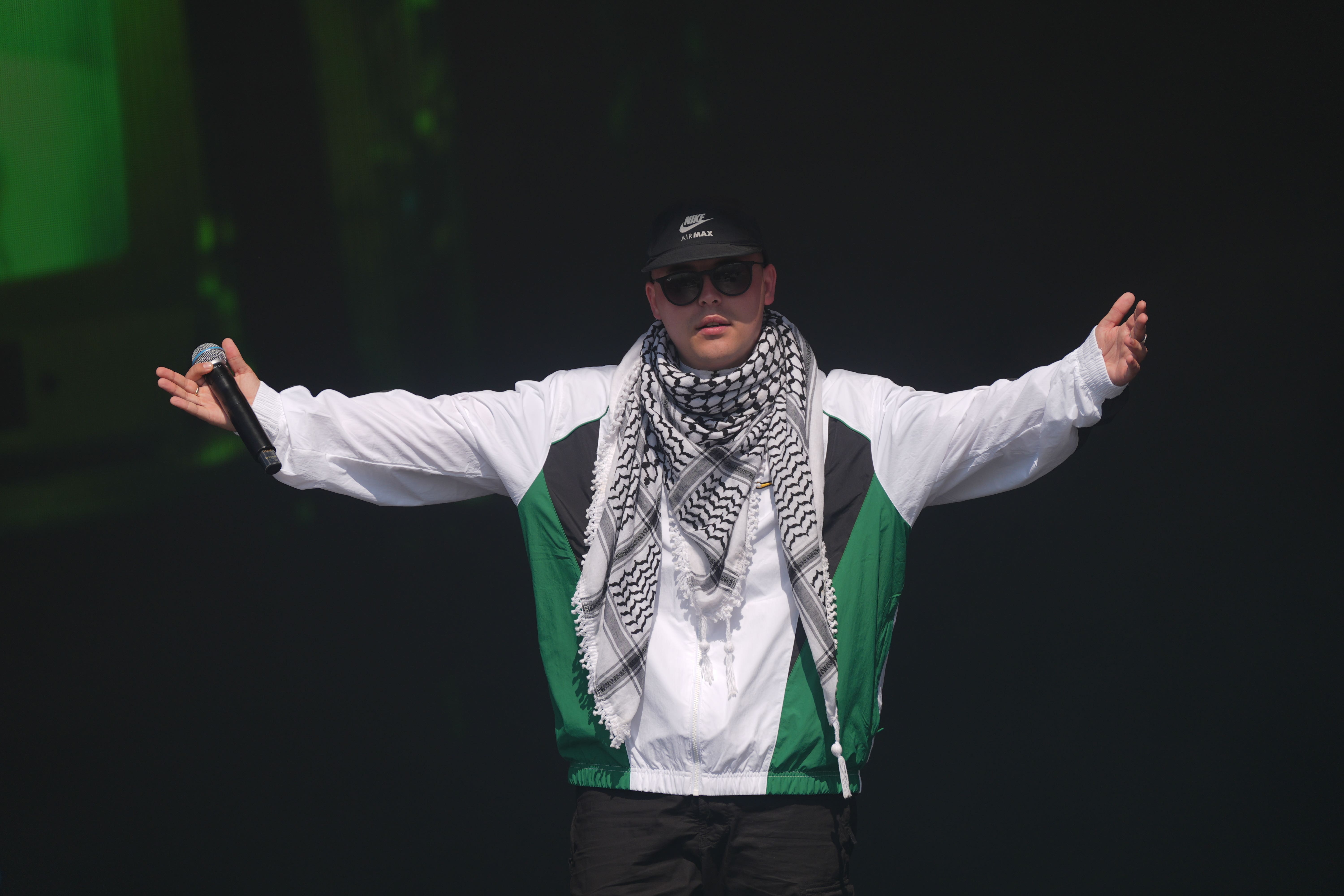

Just as outspoken are Derry-Belfast rap trio Kneecap, who eclipsed Olivia Rodrigo and Neil Young to become the most talked-about act at Glastonbury 2025 when they led chants of “F*** Keir Starmer” and “Free Palestine”. Admittedly, in this instance, Kneecap were looking outwards towards global politics rather than anything specific to Ireland – yet in the past, the band have taken homegrown issues like Irish language rights and Northern Ireland policing to task in their lyrics.

Also speaking truth to power Irish-style are post-punks Fontaines DC, whose 2022 song “I Love You” raged against the sclerotic tribalism of the Irish political system – broaching the country’s Tweedledum and Tweedledee establishment parties with its line about “the gall of Fine Gael and fail of Fianna Fáil”. These are specifically Irish references – outsiders might struggle to even pronounce Fianna Fáil, let alone tell you how it differed from Fine Gael. For that reason, it was surreal, to put it mildly, to hear Olivia Rodrigo cover the song on stage in Dublin last month. Does Rodrigo, one wonders, have strong thoughts on the merit of FF leader Charles Haughey’s austerity budgets of the late 1980s or the legacy of FG leader John Bruton’s mid-1990s rainbow coalition? It would be fantastic if she did – but even if not, there was a strange thrill hearing one of the world’s biggest pop stars venturing, however unintentionally, into the weeds of Irish politics.

Musicians are also confronting the other major issue in Ireland today – the rise of the far right and the growing anti-migrant sentiment that exploded in the November 2023 Dublin riots, during which the city centre was looted and trams set ablaze. That violence is addressed by Cork/Dublin indie band The Murder Capital on their 2025 track “Love of Country”, on which frontman James McGovern addresses the racists directly, singing: “Could you blame me for mistaking/ Your love of country for hate of man.”

Ireland’s dependence on American tech investment is meanwhile challenged on the forthcoming second album from Dublin electronic producer and poet David Balfe, aka For Those I Love, as he laments that the city is “in bed with techno-feudalism”.

It may seem ridiculous to claim that singing about politics is anything new in Ireland. The country’s folk scene, after all, is steeped in laments about British rule and the devastating impact of colonialism. However, that tradition has tended to look outward at Ireland’s shared enemies rather than examine issues closer to home. There have been outliers, of course; the Kildare folk troubadour Christy Moore has sung about the plight of Irish migrants in Britain and the early 1980s hunger strikes by Republican prisoners in Northern Ireland. He is an exception, though. Ireland’s major musical exports have rarely looked so close to home.

U2 may have sung about the Troubles and the dangerous seductions of Republican violence on “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, but they never had much to impart about the economic malaise of 1980s Ireland or the cold, dead grip of the Catholic Church. The same can be said of The Cranberries, who rightly spoke out against IRA murder with “Zombie” yet did not talk about the problems facing their native Limerick, a city with well-documented social issues. But today’s generation of songwriters are tackling the equivalent issues with conspicuous fervour: in biffing Bertie, CMAT is going where Bono would never have dared.

“Bertie is kind of symbolic of the self-serving greed that brought us to where we are and will continue with disastrous consequences,” says folk singer Martin Leahy, who wrote the ballad “Everyone Should Have A Home” in 2022 after struggling to find a house he could afford in his native West Cork. Leahy took his tune straight to the seat of power by travelling to the gates of the national parliament, Dáil Éireann, where he has played it every week for the past three years.

“I had ‘Everyone Should Have A Home’ written, and one week I decided that I would go up outside the Dáil and sing it out of pure frustration. I’d be reading articles or listening to talks on the housing crisis, and I felt totally powerless. I thought that if I went up to Dublin and sang it, that maybe I might not feel powerless any more,” he says. “I got on the bus, arrived in Dublin, and when I got off the bus, I asked the first person I saw where the Dáil was.”

“So, I went up there and every bit of the act of doing the protest was alien to me. I had never busked. Taking out the guitar, standing on the street, and starting to sing was rattling for me. But the issue, the anger, the frustration and the desperation outweighed any insecurities I had. I feel that shame is a big part around the functioning of this crisis. I’ve continued to do it every week since that day. I get lots of support from many politicians in opposition; I get ignored by politicians in power.”

In the case of CMAT and “Euro-Country” – an album of the same name arrives in August – the most poignant verse comes after she has invoked Bertie’s name, as she talks about the wave of suicides that followed the collapse of the Irish economy in 2008. “I was 12 when the dads started killing themselves all around me,” she sings. “No one says it out loud, I know it can be better if we hound it out.”

“I dug deep, did research, and the amount of male suicides that happened in Ireland at that time was astronomical,” Thompson told a newspaper recently. “When I hit secondary school, teenage boys started killing themselves as well; that was very common where I grew up. I think it was a kind of chain reaction as a result of the economic downturn.”

“These things have a massive spillover. That’s got to be called out. I have had enough of things being shoved under the carpet, it does no good for anyone,” agrees songwriter Áine Duffy, whose 2024 electro-folk single “Move Along” is about the financial disparities fuelling the property crisis: “There’s a lot of lovely places/ But they’re Airbnb’d/ I think the government should fix it/ Keep the families off the streets.” It had “a horrible effect that still lingers,” says Duffy. “The Celtic Tiger [the period of breakneck economic growth of the 1990s and early 2000s that came crashing down in 2008] makes me sick to the stomach.”

Duffy’s experience of life in Ireland is similar to that of Leahy in that she has also struggled to find a roof over her head. This motivated her to write “Move Along” and to build a €12,000 micro-home using timber slats and a steel frame on her parents’ land. “I was moving from one spot to another and had been told the room and house I put a lot of work into was going to be put on Airbnb. I was wondering where me and my dog were going to go.”

While Ireland’s new generation of politically outspoken artists won’t solve the many problems ailing the country, they should be praised for calling out its ills. In a society where too much has been swept under the carpet for too long, simply acknowledging these issues feels radical. To outside ears, CMAT’s Bertie-bashing may feel like run-of-the-mill protest pop. In Ireland, it is something we have never heard before.

Regina Spektor tells pro-Palestine protesters at concert: ‘You’re yelling at a Jew’

Kneecap say Hungary ban an attempt to ‘silence’ pro-Palestine voices

Kneecap and Massive Attack launch pro-Palestine music alliance

French town withdraws music festival funding after Kneecap booking announced

Big Thief: ‘Our bassist leaving was like a divorce... the change is very significant’

Tim Minchin: ‘Trump is partly an outcome of the smug progressive left’