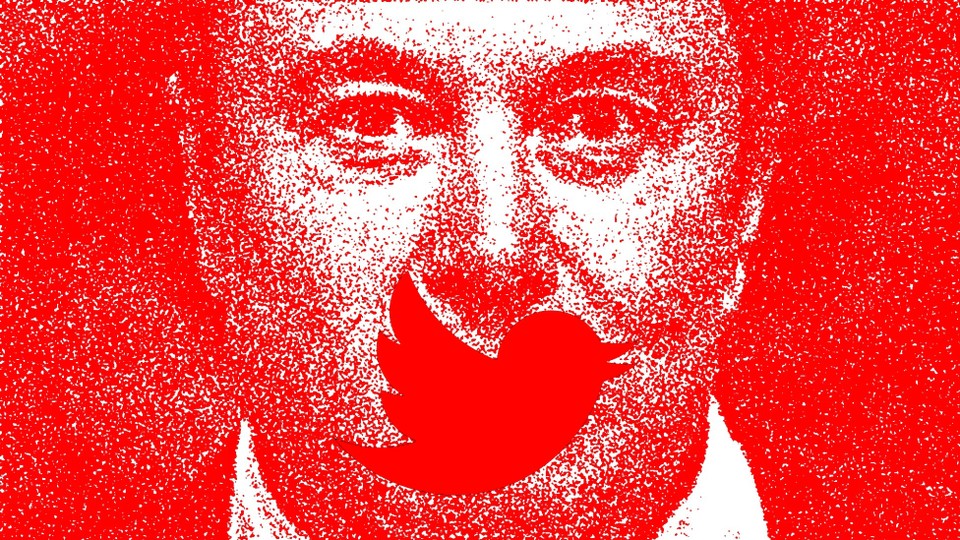

When the right-wing billionaire Elon Musk wanted a journalist to spread the word about supposed left-wing censorship under Twitter’s previous ownership, he went to Matt Taibbi. But last week, Twitter began to throttle traffic to the newsletter platform Substack, where Taibbi does most of his writing, and apparently began hiding Taibbi’s tweets in Twitter's search results. Musk’s chosen conduit for exposing what he described as past Twitter’s censorship was now being censored by Musk’s Twitter.

Although Musk has insisted the temporary throttling of Substack was a mistake, Taibbi claimed that it was in response to a “dispute” over the company’s new Twitter-like service.

Blocking access to a competitor may seem, well, at odds with the “free-speech absolutism” that Musk has proclaimed and that admirers like Taibbi have praised. As the reporter Mike Masnick writes, the above behavior clearly falls into what Musk fans described as censorship under Twitter’s previous ownership. But it’s consistent with what more perceptive observers noted about Musk as he was considering buying the network: The mogul’s treatment of union organizers and whistleblowers suggested that “free-speech absolutism” was mostly code for a high tolerance for bigotry toward particular groups, a smoke screen that obscured an obvious hostility toward any speech that threatened his ability to make money.

Not since Donald Trump has liberal judgment about the focus of a right-wing cult of personality been so swiftly vindicated. During his tenure at Twitter, Musk has suspended reporters and left-wing accounts that drew his ire, retaliated against media organizations perceived as liberal, ordered engineers to boost his tweets after he was humiliated when a tweet from President Joe Biden about the Super Bowl did better than his own, secretly promoted a list of accounts of his choice, and turned the company’s verification process into a subscription service that promises increased visibility to Musk sycophants and users desperate enough to pay for engagement. At the request of the right-wing government in India, the social network has blocked particular tweets and accounts belonging to that government’s critics, a more straightforward example of traditional state censorship. But despite all of that, he has yet to face state legislation alleging that what he does with the website he owns is unconstitutional.

That’s notable because, until Musk bought Twitter late last year, conservatives were arguing that the company’s moderation decisions violated the First Amendment, even though Twitter is a private company and not part of the government. Now that Musk is using his editorial discretion as owner of the company to promote people and ideas he supports—primarily right-wing influencers—and diminish the reach of those he does not, the constitutional emergency has subsided. At least until his allies and defenders on Substack found themselves unable to promote their work on Twitter, free speech had been restored, because “free speech” here simply means that right-wing ideas and arguments are favored. This outcome—that Twitter under Musk would favor right-wing content—was predictable, and I’m saying that because I wrote last April that that’s what would happen.

The episode reveals something important about the way that many conservative jurists and legal scholars now approach the principle of free speech. Florida and Texas passed laws prohibiting social-media companies from moderating user-generated content, in retaliation for what they characterized as liberal “censorship.” A federal judge appointed by Trump, Andrew Oldham, then upheld the Texas law with a ruling that scoffed at the idea that “editorial discretion” constituted a “freestanding category of First-Amendment-protected expression” and insisted that the platforms’ moderation decisions did not qualify for that protection. Whether “editorial discretion” is a “freestanding” category of protected speech is irrelevant; engaging in protected speech is impossible absent the freedom to decide what to say, or for that matter what ideas are worthy of publication. Conservatives agree, as long as those platforms are conservative; right-wing platforms such as Parler and Truth Social have strict moderation policies that conservatives are not challenging as unconstitutional.

Like the newfound opposition to vaccine mandates, this blinkered view of free speech was met by conservative judges eager to validate right-wing cultural shifts, no matter how bizarre or contradictory, through their strained method of constitutional interpretation. The ghosts of the Framers may be summoned through the necromancy of undead constitutionalism, through which the authors of our founding document can be confirmed to have had the same concerns and priorities as extremely online conservatives. Now that Musk is utilizing his editorial discretion to move the social network in a right-wing direction, however, no one is insisting that his exercise of editorial discretion violates the Constitution—not even his liberal critics.

Conservatives built an entire body of jurisprudence around the First Amendment’s protection of corporate speech when large corporations were reliably funding Republican causes and campaigns—the late Justice Antonin Scalia declared in the Citizens United decision that “to exclude or impede corporate speech is to muzzle the principal agents of the modern free economy.” But once some corporate actors decided it was in their financial interests to make decisions that the GOP disliked, conservative lawyers then turned around and argued that speech was no longer protected if it was used for purposes they opposed. If your freedom of speech is only protected when it aligns with the ruling party, then you do not have a right to freedom of speech.

Faced with right-wing outrage over the moderation decisions of social-media platforms, conservative judges turned the First Amendment upside down by upholding—or signaling their sympathy with—state laws designed to punish social-media platforms for being insufficiently conservative. They invented a “conservative right to post” in which the First Amendment restricted private platforms the way it does the government, but only if those platforms were perceived as liberal. Perhaps nowhere is this inversion of the First Amendment more clear than on the issue of abortion rights; the same lawmakers insisting that the content-moderation policies of private firms violate the First Amendment are feverishly attempting to criminalize online speech related to abortion.

The platforms targeted by anti-moderation laws were never liberal; they imposed moderation policies because it is difficult to maintain advertising revenue when your platform is overrun by teenage Nazis with anime avatars and aspiring far-right intellectuals desperate to impress them. Musk’s changes were far more ideologically driven and have reportedly, by his own evaluation, halved the value of his company.

Conservatives rapidly reversed their stance on corporate free-speech rights when they were angry at Twitter for being too left-wing, then changed their mind again once Musk bought Twitter and began amplifying right-wing voices at the expense of others. Musk owns the platform, and he can use it to magnify or ignore whatever ideas and sources he chooses. But it’s not a right that most of these conservative, self-styled defenders of free speech think you should have. For them, free speech is when they can say what they want, and when you can say what they want.