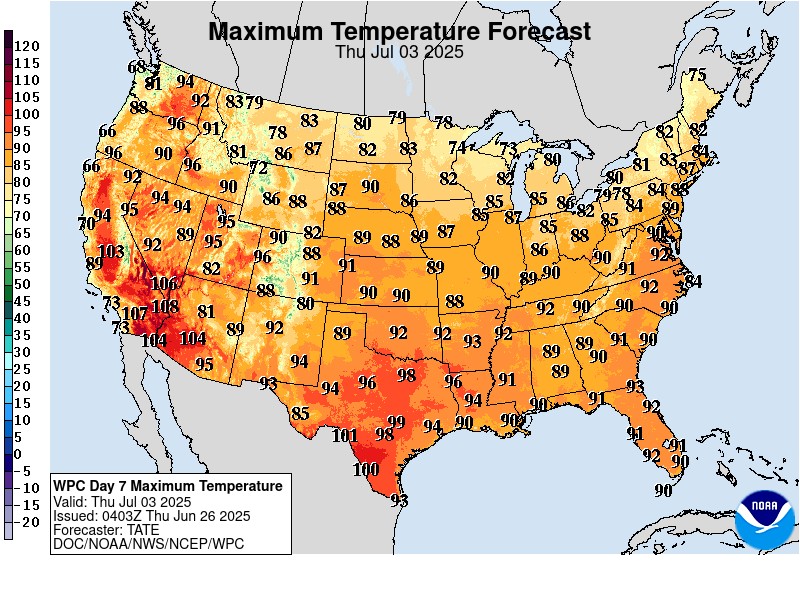

The National weather forecast for this Thursday before Independence Day 2025 shows high temperatures reaching to at least 90 degrees across the southern half of the nation, from the middle-Atlantic coast, westward through the Greater Ohio Valley, Central Great Plains, Texas and Oklahoma and down into the Desert Southwest.

Ninety-degree temperatures will also be attained over California (save for along the Pacific Coast), as well as Nevada, central and eastern portions of Oregon and Washington State and most of Idaho. Temperatures at or above 100 degrees are expected for southwest Texas, southern and western Arizona, southern Nevada and southeast California. Some desert locations might see ambient air temperatures approach 110 degrees.

With such hot temperatures as these, it might be a surprise for you to hear that on Thursday, July 3 at 3:55 p.m. EDT (1955 GMT), our Earth will reach that point in its orbit where it is farthest from the sun in space.

Since Kepler's laws of motion dictate that celestial bodies orbit more slowly when farther from the sun, we are now moving at our slowest pace in orbit, slightly less than 18 miles per second (29 kilometers per second) compared to just over 19 at perihelion.

Called aphelion, the sun at that moment will be 94,502,939 miles (152,087,738 km) from our Earth (measured from center to center), or 3,096,946 miles (4,984,051 km) farther as compared to when the Earth was closest to it (called perihelion) last Jan. 4. Put another way, we are 16.62 light seconds farther from our local star than at perihelion in January. The difference in distance is equivalent to 3.277 percent, which makes the sun appear 6.55 percent dimmer now than in January; A change of only one part in 30.

The tilt, not the distance makes the difference

Indeed, it's probably no surprise that if you ask people in which month of the year they believe that the Earth is closest to the sun, most probably would say we're closest during June, July or August. But our warm weather doesn't relate to our distance from the sun. It's because of the 23.5-degree tilt of the Earth's axis that the sun is above the horizon for different lengths of time at different seasons. The tilt determines whether the sun's rays strike us at a low angle or more directly.

At New York's latitude, the more nearly direct rays at the summer solstice of June 20 bring about three times as much heat as the more slanting rays at the winter solstice on Dec. 21. Heat received by any region is dependent on the length of daylight and the angle of the sun above the horizon. Hence the noticeable differences in temperatures that are registered over different parts of the world.

A climatological fallacy

When I attended Junior High School, my earth science teacher told all of us that because we were farthest from the sun in July and closest in December, that such a difference would tend to warm the winters and cool the summers — at least in the Northern Hemisphere.

That certainly seemed to make sense, and yet the truth of the matter is that the preponderance of large land masses in the Northern Hemisphere works the other way and actually tends to make our northern winters colder and the summers hotter!

Interestingly, the times when the Earth lies at its closest and farthest points from the sun roughly coincide with two significant holidays here in the United States: We're closest to the sun around New Year's Day and farthest from the sun around Independence Day.

For those living in Canada, aphelion nearly coincides with their national holiday — Canada Day — on July 1.

But actually, depending on the year, the date of perihelion can vary from Jan. 1 to 5 and the date of aphelion can also vary from July 2 to July 6.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.