The Netherlands is bracing for a pivotal general election on 29 October, with more than 13 million eligible voters set to decide on the country's future direction amid fervent debates over EU membership, the war in Ukraine and immigration policy. Polls indicate that the far-right PVV party is likely to wield significant influence, accelerating a trend seen in other European states.

Dutch voters head to the ballot box on Wednesday for an election that will be closely watched around Europe for the performance of the far-right led by anti-Islam, anti-immigration politician Geert Wilders.

Polls suggest Wilders and his PVV Freedom Party could repeat their stunning election success from 2023 and top the vote, although the gap to other parties has narrowed.

Even if he were to win, he is unlikely to become Prime Minister, as all other parties have ruled out a coalition with him.

Campaigning reached fever pitch this week, with several major debates between the main party leaders.

The leaders of the three other major parties - GL-PvdA (centre-left alliance between the Labour Party and Greens), the Christian Democrats (CDA) and the liberals (VVD) - accused Wilders of "not having done enough" during the last two years when his party was in power, whilst categorically excluding any future cooperation.

Frustrated that he could not push through his hard-line anti-immigration plans, Wilders pulled out of a coalition with the VVD, the farmers' party BBB and the New Social Contract party NSC (a splinter from the Christian Democrats), causing the collapse of the government on 7 July.

Since then, a caretaker government has been running the day-to-day governance of the Netherlands, whilst political parties started to solidify their positions, hoping to gain a place in a new coalition after the elections on Wednesday.

Domestic priorities and immigration

Apart from affordable housing and healthcare, immigration features high on the campaign agenda, with half the electorate calling it their main concern.

The PVV is pushing a hardline anti-asylum stance, advocating a "total halt" to new arrivals and the deportation of dual nationals convicted of crimes - measures that directly contradict European and international law.

The BBB (Farmers' Party) and VVD also offer tough measures, including limits on asylum applications and the criminalisation of undocumented status. GL-PvdA, by contrast, supports civilised reception for undocumented migrants and fair arrangements for those refused residence, reflecting a more compassionate approach.

Support for Ukraine and EU membership

On EU membership, the major parties' views reflect a divided society. Wilders' PVV is openly Eurosceptic, proposing a "Nexit" and opting out of core EU migration policies, whilst seeking limits on Brussels' ability to dictate Dutch laws, especially on pensions and agriculture.

By contrast, the VVD remains strongly pro-European, focusing on reform from within rather than challenging Dutch participation. The CDA and GL-PvdA are generally pro-EU, arguing for continued Dutch leadership in European cooperation and defence.

Despite the far right's rise, the most recent coalition agreement maintains strong support for military assistance to Ukraine and the NATO alliance – a stance also championed by centrist and mainstream parties.

However, Wilders' PVV has voiced a desire to halt Dutch arms supplies to Ukraine, preferring to redirect spending to domestic defence priorities. This duality means future Dutch policy will likely balance continued backing for Ukraine with new debates on spending and priorities.

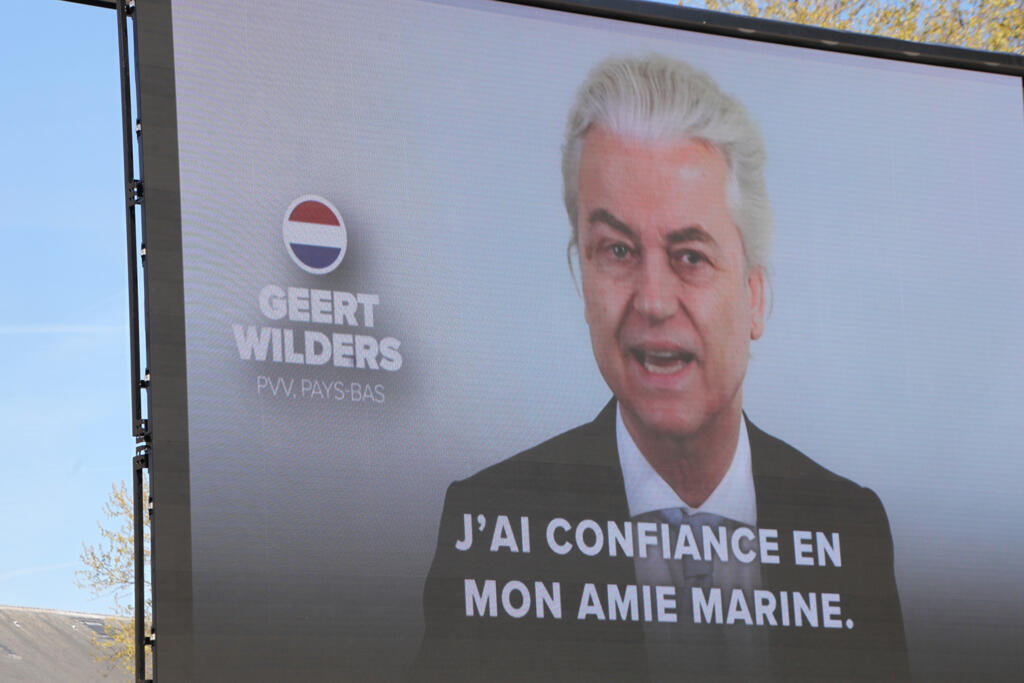

Wilders, Le Pen and the rightward shift

Over the past decade, ties between Geert Wilders and France's Marine Le Pen have grown closer, forming one of Europe's most visible far-right alliances.

Le Pen openly celebrated Wilders' electoral success, calling it an inspiration for protecting national identities across the continent.

This partnership symbolises a broader shift: as Wilders' PVV steers the Dutch political agenda, a right-leaning bloc is consolidating in opposition to Brussels on migration, attracting supporters from France, Italy and Germany.

The implications could be profound. A closer PVV-Le Pen axis empowers eurosceptic forces, undermines traditional EU consensus on asylum and human rights, and prompts Brussels to brace for further opposition on key policy matters.

The Netherlands, long viewed as an anchor for European integration, now finds itself at the vanguard of a continent-wide swing to the right.

From Washington to Warsaw: how MAGA influence is reshaping Europe’s far right

Or does it? Whilst the PVV gained an unprecedented 37 seats in the 150-seat Parliament just two years ago, and all opinion polls indicated a major lead over the other parties, that advantage began to shrink suddenly just a week before the elections.

According to polling institution Maurice de Hond, Wilders' PVV would now secure 29 seats, whilst the Christian Democrats, Liberals and centre-left party have gained considerably since 2023. And as all parties have now indicated that they will not cooperate with a possible PVV-dominated coalition, the chances of Wilders steering Dutch politics for another term are becoming slimmer.

The main players

Geert Wilders (PVV)

The peroxide-blond populist has been the face of Dutch Euroscepticism since 2006, living under armed guard and vowing to freeze asylum and rewrite relations with Brussels. Wilders' party has only one real member – himself – emphasising strong central leadership, albeit with little internal dissent.

Frans Timmermans (GroenLinks-PvdA)

Erudite, experienced and formerly a European commissioner, Timmermans leads the left-green alliance, arguing for climate justice and humane migration. Though knowledgeable, he has faced challenges in winning the hearts of ordinary voters.

Dilan Yeşilgöz (VVD)

Now leading the centre-right after Mark Rutte, Yeşilgöz's personal story as a former refugee merges with tough rhetoric on migration and a strong social media presence. She champions business-friendly reforms and increased defence spending, but takes a strict position on asylum.

Henri Bontenbal (CDA)

A relative newcomer, Bontenbal revitalised the traditional Christian Democrats with policies aimed at housing reform and cautious conservatism. His leadership is credited with a renewed focus on centre-ground policies and appeals to former supporters of New Sociaal Contract, a party that split from the CDA but was decimated after its leader left politics.

(with newswires)