Missouri lawmakers are considering a proposal to abolish the state's income tax and replace it with a sales tax. They're not alone: Last year, Mississippi approved legislation that will decrease the state income tax over several years until it's eliminated. That follows in the footsteps of Kentucky and Oklahoma. New Hampshire, which has no income tax, phased out its tax on interest and dividends. Several states making the move are considering sales taxes to fill the revenue gap, and they have the backing of the White House. But a new report warns that sales taxes may have to be higher than anticipated to make up the difference—unless state governments shrink in size and expense.

States Move To Shed a Hated Tax

"Mississippi will no longer tax the work, the earnings, or the ambition of its people," Mississippi Gov. Tate Reeves boasted last March in a statement that captured low popular opinions of income taxes (and taxes in general). "I believe in a simple idea: that government should take less so that you can keep more. That our people should be rewarded for hard work, not punished. And that Mississippi has the potential to be a magnet for opportunity, for investment, for talent—and for families looking to build a better life."

Unmentioned, but a worthy addition to Reeves' observations about income taxes, is the inquisitorial nature of their enforcement. People must open their financial lives to government officials, allowing collectors to know how much they make and from whom, and to track flows and expenditures. The intrusive nature of income taxes is compounded by dueling guesses between taxpayers assessing their liability and officials who have the final word (and the force of law behind them).

In coverage of the recent move to jettison income taxes, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) reports "the statutes set to eliminate income taxes in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Oklahoma have all followed the same basic principle: When the state has extra funds available, the first use of them should be to put money into taxpayer pockets, prioritizing reducing income tax rates over increasing government spending." Conditions—triggers—must be met before rates decline on their way to zero.

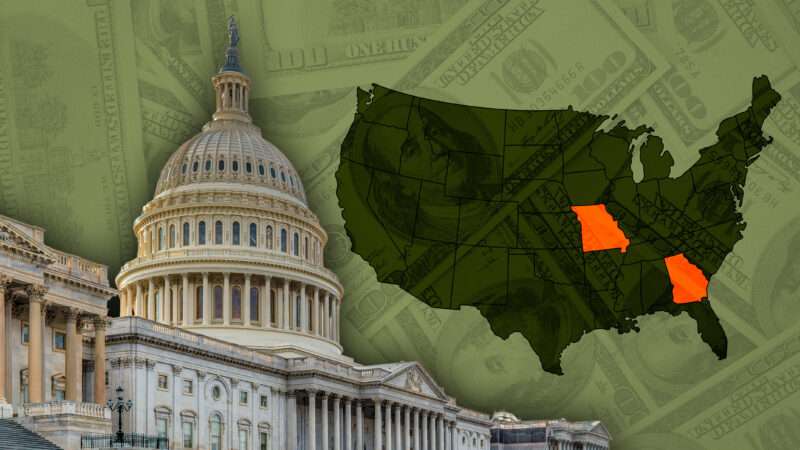

With income taxes going away, that raises questions about the implications for state finances since revenue will decline. Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe proposes to hike sales taxes to make up the shortfall, though he vowed in his 2026 state of the state address that he will "never support extending sales taxes on agriculture, healthcare, or real estate." Georgia is considering a similar proposal. In this they have the support of the White House Council of Economic Advisors (CEA).

White House Supports Dumping State Income Taxes

In a January 28 report, the CEA points out that states without income taxes lead the way in attracting and retaining residents and businesses. In part, that's because "workers and businesses can avoid taxes by moving to lower-tax jurisdictions, and high-income individuals—those with the greatest tax liability and often the most career flexibility—are particularly responsive to income taxes." The report adds that throughout the 20th century, "implementation of a state income tax led to significant population losses. The out-migration was so substantial that states saw little net revenue gain from their new income taxes—the expanded tax base was largely offset by the loss of taxpayers who left."

The CEA concludes that most states could replace income tax revenue with "an average state sales tax rate of under 8 percent under full revenue replacement with no limits on spending growth." With spending growth limits, states could offset lost revenue from abolished income taxes with "an average state sales tax rate of 6.2 percent."

That sounds like a fair tradeoff. But the Tax Foundation's Jared Walczak finds it far too optimistic.

A Higher Price Tag Than Advertised

Walczak agrees that "reducing income tax burdens and shifting toward well-designed sales taxes is pro-growth tax policy." He also concurs with the CEA's prediction of a significant increase in prosperity produced by a revenue-neutral shift from income to sales taxes. But he worries the CEA is pitching sales tax rates at far too low a level to replace income tax revenue. Unfortunately, he says, "the CEA's calculations omit important factors and envision a sales tax base that violates federal law, among other serious impediments."

The CEA's proposal, for example, would tax all healthcare expenditures, even though many are off-limits to taxation under current law or involve no taxable transaction. Also, to arrive at the average replacement tax rate, the CEA assumed a sales tax on transactions in all states, "even those that already forgo an income tax, a sales tax, or both," Walczak writes. That distorts the economic calculations.

The CEA report also assumes 100 percent compliance—something never achieved by any tax regime.

By his own calculations, including an assumption of 89 percent compliance, Walczak arrived at replacement sales tax rates of 12.08 percent on the low end and what he believes to be a more realistic rate of 17.51 percent. Ignoring the CEA's proposed taxable base in favor of raising existing tax rates arrived at slightly lower rate of 15.66 percent.

Interestingly, the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI), which prefers retaining the income tax, estimates a sales tax of 15.44 percent is required to replace lost revenue. That's closer to Walczak's figure than to the 7.19 percent the CEA proposes for full revenue replacement in the Peach State.

"Through flawed estimates, the CEA dramatically overstates the ease with which states could replace their income taxes," Walczak cautions. "Real reform is worth doing—but that starts with realistic figures."

An Opportunity for Smaller Government

Walczak and GBPI's Daniel Kanso both work from the credible assumption that many people would find high sales rates daunting, with Kanso emphasizing "painful tradeoffs" to make the transition work. But the switch from income taxes to sales taxes could also be an opportunity. If paying 12 or 15 or 17 percent in tax on every transaction is painful, it's pain that has been hidden from people through income withholding taxes even as the money was extracted behind the scenes. Mitigating that pain could be accomplished through smaller, leaner government that spends less and requires less revenue.

At the same time, smaller state governments funded by sales taxes wouldn't need to peer over everybody's shoulders, violating privacy and imposing a financial surveillance state.

Nine states currently have no state income tax, with several others planning to join them in the next few years. To prevent sticker shock at the cost of making the change, elected officials need to be honest about the cost of replacing the lost revenue with money from other sources, such as sales taxes. Or they could look at the end of state income taxes as an opportunity to shrink state government.

The post Dumping State Income Taxes Could Mean High Sales Taxes—or an Opportunity for Smaller Government appeared first on Reason.com.