Vice presidents are selected for many reasons. They may balance the ticket, helping the top man in a region or a section of the electorate where he is not strong, just as Lyndon Johnson helped John F Kennedy in 1960 to win his home state of Texas (and with it, the White House).

Or they may reinforce a candidate’s appeal, just as Al Gore underlined Bill Clinton’s message of youth, energy and new ideas in 1992.

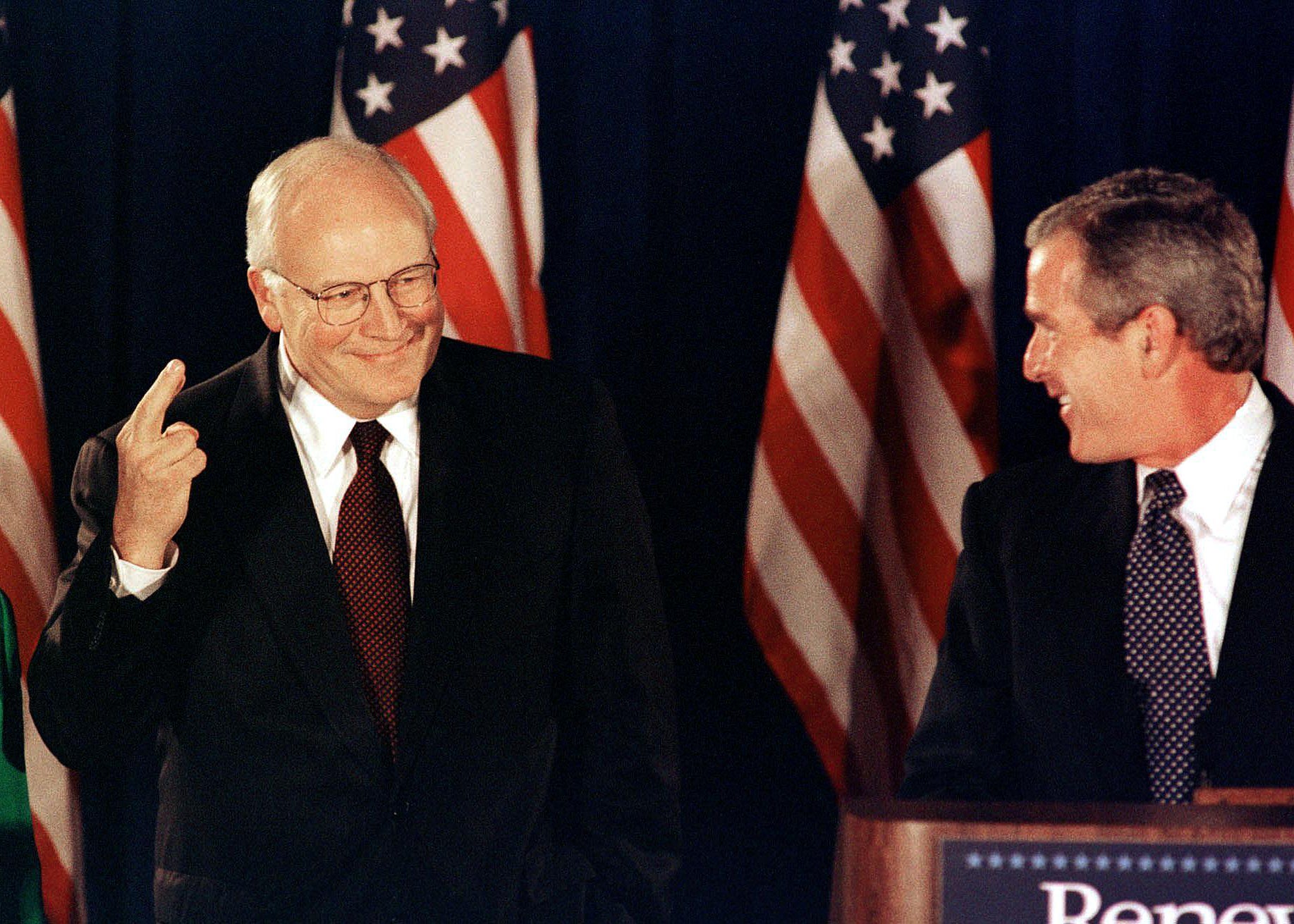

In 2000, Dick Cheney fit neither model. His home state of Wyoming was a negligible electoral prize, while in contrast to George W. Bush’s promises of change, he seemed the incarnation of eternal, bureaucratic Washington — so much so that some feared he would lose, not win, votes for his boss.

Yet, from this unpromising start, he turned himself into the most influential vice president in modern U.S. history, transforming a job once famously described as “not worth a bucket of warm spit” into a U.S. version of the office of prime minister, subordinate to, but almost coequal of, the presidency itself.

That summer, Cheney was not the obvious first choice for running mate. But four years in charge of the Pentagon under the elder George Bush had sealed his place as “one of us” for the fiercely protective Bush family clan, which prizes loyalty above all else.

After securing the Republican nomination, the younger Bush named Cheney to lead his search team for a vice president. A few weeks later, he concluded that the head he really wanted belonged to none other than the head-hunter himself.

In fact, the choice made eminent sense. Cheney did offer attributes — of gravitas, top-level experience and knowledge of foreign policy issues — that Bush at that stage could never match.

It soon became clear he would have an authority and influence unrivalled by any 20th-century predecessor — so much so that the president, not the vice president, was said to be the proverbial “heartbeat from the Oval Office”.

The jibe played on Cheney’s long history of heart trouble. But it also reflected how the former congressman, cabinet member and White House chief of staff was shaping policy across every field of the government with which he had been associated, in one role or another, for over three decades. If anything, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the defining moment of the Bush presidency, only cemented his power.

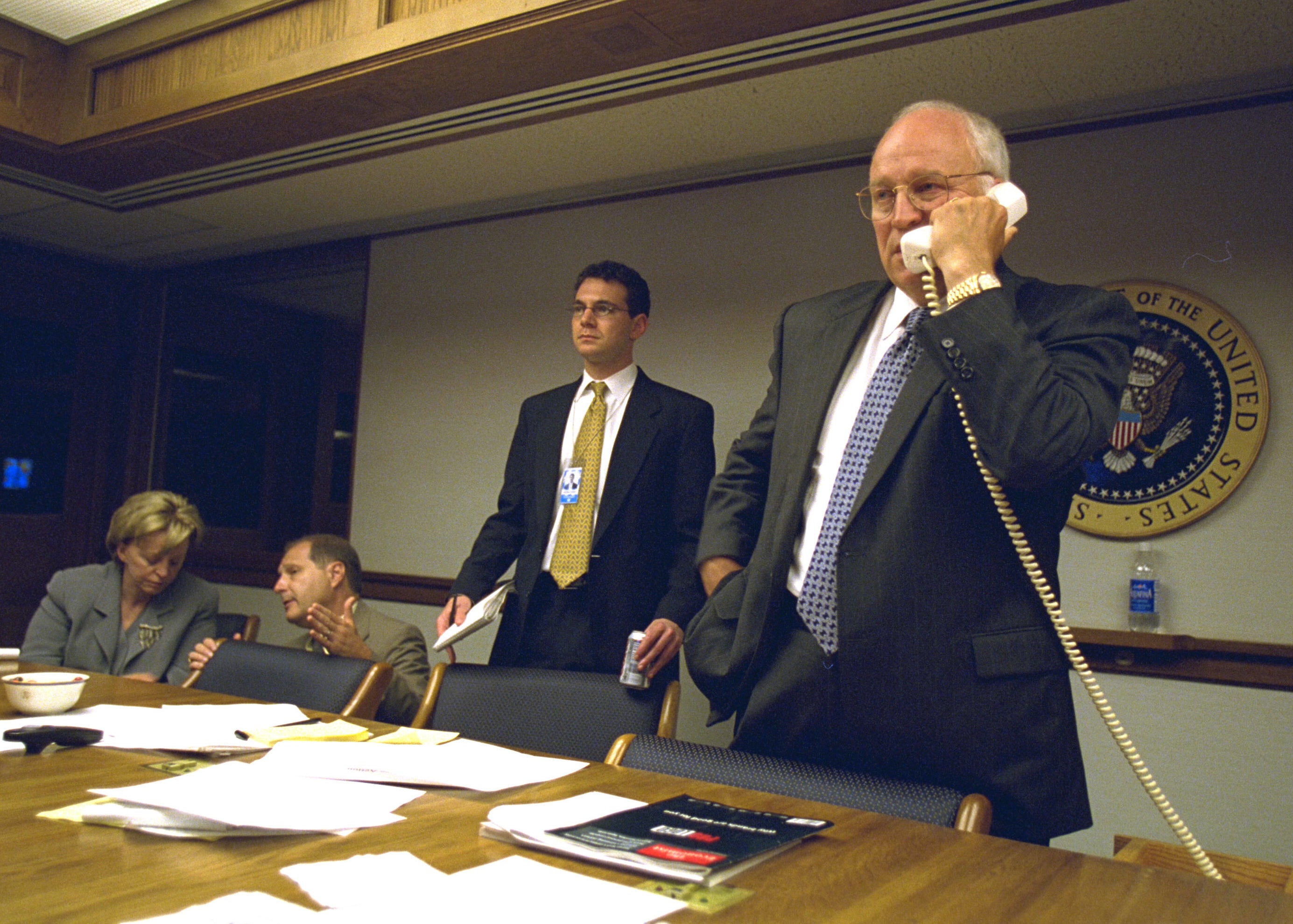

Early that terrible day, while Bush was on a scheduled trip to Florida to promote his education reforms, it was Cheney, from the situation-room bunker deep beneath the White House, who took charge in the immediate aftermath of the attacks.

More than anyone, he convinced Bush that terrorism was an existential threat to the U.S.. He was arguably the driving force behind the invasion of Iraq, utterly persuaded of the danger posed by Saddam Hussein, and dismissive of any intelligence that contradicted that view.

Cheney was obsessed with secrecy, with American power, and preserving the authority of the president to project that power as he saw fit. In the months after 9/11, he operated from a “secret, undisclosed location” — a phrase that would become rich fodder for the late-night comedians.

Reticent in habit but steely of purpose, Cheney was often seen as the mentor of the neo-conservatives who inspired U.S. foreign policy and who, since the late 1990s, had advocated for the invasion of Iraq to promote reform across the Middle East.

But the vice president’s belief in the use of force reflected less American idealism than a Hobbesian pessimism, that the world was a dark jungle in which only the strongest and most ruthless would survive.

Hence, even after the appalling scandal of Abu Ghraib when U.S. soldiers were found to have tortured Iraqi prisoners, Cheney’s stubborn opposition to legislation that specifically barred the CIA from employing torture on terrorist suspects, and his forthright defence of domestic wiretapping by the super-secret NSA spy agency, without warrants. In the new war on terror, he argued, America has to do what it takes.

Cheney was the son of a middle-ranking soil conservation official for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. As a small child, he moved with his family from Nebraska to Casper, Wyoming, where he captained his high-school football team and won a scholarship to Yale.

After a year, he dropped out and returned to the West to become a contract worker. In 1963, however, he resumed his academic career at the University of Wyoming and never looked back.

He took a bachelor’s and master’s degrees in political science, married his high-school sweetheart, Lynne Vincent, and moved first to Madison, Wisconsin, as an aide to the governor, and then to Washington as an intern for William Steiger, one of the state’s Republican congressmen.

Once arrived in the capital, Cheney soon showed his gifts as an administrator and bureaucratic operator. Steiger later called his 27-year-old aide “one of the brightest, most perceptive and sensitive people I’ve ever worked with.”

Then in 1969, after Richard Nixon became president, Cheney was spotted by Donald Rumsfeld, a former congressman who had just been appointed director of the Office of Economic Opportunity. Cheney became Rumsfeld’s deputy, and for eight years their careers advanced in lockstep, from the middle echelons of the Nixon administration to the summit of Gerald Ford’s White House.

As the Watergate scandal engulfed Nixon, Rumsfeld became transition director and then chief of staff to the 38th president, with Cheney as his deputy.

In 1975, Rumsfeld went to the Pentagon for his first stint in the job he would hold in the Bush/Cheney administration a quarter of a century later. His deputy was promoted to chief of staff, a post in which his quiet competence made him, in some respects, the second most powerful man in the federal government.

Cheney, however, could not save Ford from defeat by Jimmy Carter in 1976. Instead, he returned to Wyoming and in 1978 won the state’s lone congressional seat, to which he was re-elected five times.

Capitol Hill, with its premium on skilled maneuvering, backroom deals, and institutional empire-building, suited him perfectly. Within three years, he had become chair of the influential Republican Policy Committee and, by 1988, had risen to become minority whip, the second-ranking Republican position in the House of Representatives.

Cheney’s voting record was staunchly conservative. He was a fervent tax-cutter, an unrelenting advocate of higher defence spending, and an opponent of abortion under any circumstances. But his low-key, non-confrontational style blunted the enmity of his foes.

Back in those days, at least, he had the priceless knack of masking hard-line views with an affable manner and his trademark lopsided smile.

When the new president, George Bush, turned to him in March 1989, after his first nominee for Defense Secretary, John Tower, had been rejected by the Senate, there was little doubt Cheney would be confirmed. He quickly took the measure of the Pentagon’s vast bureaucracy.

Barely six months into his tenure, he helped organise “Operation Just Cause” to oust Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. A year later, he was an architect of the 1991 Gulf War that drove Saddam Hussein from Kuwait.

Rarely had the U.S. war-making machine functioned as well. Credit was due to Colin Powell, Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to the president’s national security adviser, Brent Scowcroft, and, of course, to the coalition-building skills of George H.W. Bush himself.

But Cheney, too, played a considerable part, unflappable and respected both by Pentagon bureaucrats and the men on the front line — despite the fact he had used student and family deferments to avoid service in Vietnam.

As always, he operated through a small group of trusted aides, prizing discretion and secrecy above all. Occasionally, of course, the real Cheney would break through in public, as when he betrayed his visceral anti-Communism and mistrust of the Soviet Union by forecasting (rightly) that Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms would fail and (wrongly) that he would be followed by a virulently anti-Western regime.

But in those days, such lapses were quickly forgiven; among Dick Cheney’s old gifts was that of making few enemies. In November 1992, Bush’s defeat by Bill Clinton seemed to have ended his political career, but a powerful job in business soon came his way.

With his top-level contacts in Washington and the Arab world, Cheney was a natural choice to become chair and CEO of the Dallas-based Halliburton, the world's largest oil services company.

Cheney’s tenure, from 1995 to 2000, would become deeply controversial in the Iraq war of 2003 and its chaotic aftermath. But it had significant consequences.

Indirectly, his Halliburton spell further strengthened his ties with the Bushes, another family active in the Texas oil industry. It was also a pointer that the second Bush would lead the most business-friendly administration in recent American history.

In 1995, Cheney toyed with the idea of running for president the following year, but wisely abandoned it. He had no political or fundraising base within the party to speak of. He was a monotonous, uninspiring speaker, and the doubts over his health would never have withstood the scrutiny faced by a White House candidate.

By the time he became vice president, he had suffered at least four heart attacks, had undergone quadruple-bypass surgery and two angioplasties, and he experienced minor health scares in 2001, 2005, and 2006.

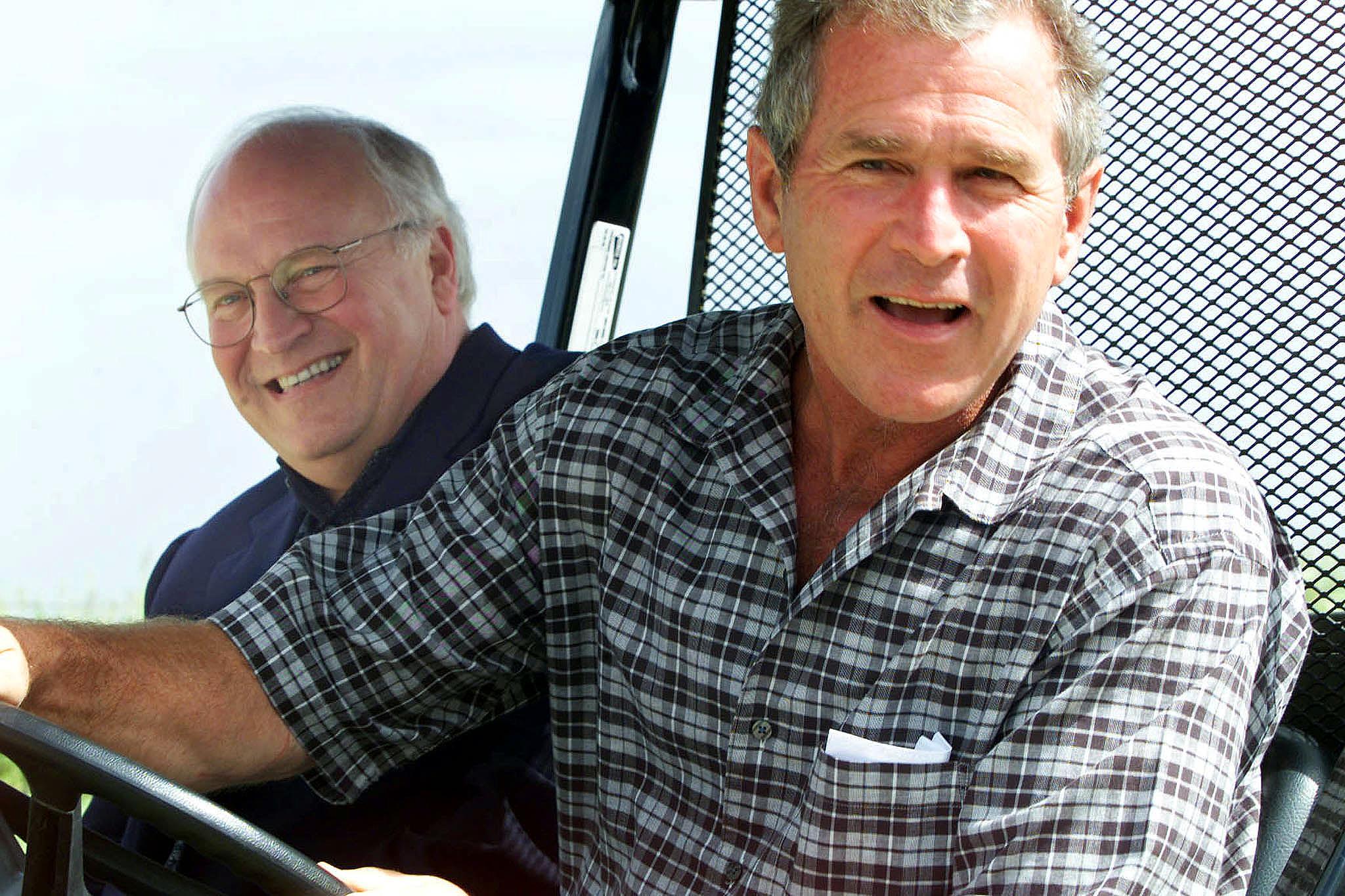

In a sense, however, fragile health and advancing years only enhanced Cheney’s power. Unlike most vice presidents, Cheney harboured no desire for the top job. As such, his discretion and loyalty were even more prized by Bush.

Backed by his own tight-knit and assertive national security staff, he emerged as the powerbroker of a national security team containing such independent-minded heavyweights as Powell and Rumsfeld.

The old Cheney/Rumsfeld alliance dominated the Bush administration, setting its hard-nosed, unilateralist style, and routinely outmanoeuvring the more conciliatory Powell at the State Department.

When U.S. forces captured Baghdad in April 2003, Cheney’s prestige was at its zenith. But as the occupation bogged down, the vice president’s reputation fell along with it.

The absence of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) called into question Cheney’s judgment. The discrediting of Ahmed Chalabi, the Iraqi exile leader who had wormed his way into the Pentagon’s and vice president’s favour, was another blow.

Halliburton, which was awarded major no-bid contracts for the post-war reconstruction of Iraq, meanwhile became a byword for corporate cronyism, corruption and profiteering, and Cheney’s association with it threatened to be a real problem in George W. Bush’s re-election campaign.

For a while, there was even talk that he would be dropped from the ticket. But in reality, Cheney’s position was unassailable, even discounting Bush’s overriding loyalty to those loyal to him.

As a link to the party’s vital social conservative base, Cheney was essential. To have jettisoned him would moreover have been a fundamental admission of error by a president always loath to concede the slightest mistake.

The second Bush term did nothing for his reputation. There was the torture controversy, the resignation of Lewis Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff, after being indicted in the CIA leak affair, and mounting evidence of how he had leaned on the intelligence agencies to bolster the pre-war WMD case against Saddam.

As his popularity ebbed further, even the lopsided smile of yesteryear gave way to a seemingly permanent snarl.

“I consider Cheney a good friend – I’ve known him for thirty years. But Dick Cheney, I don’t know any more,” Brent Scowcroft, his colleague under the elder George Bush, told The New Yorker magazine in late 2005, more in sorrow than in anger. Many shared that view. But no amount of complaining will change the reality that Dick Cheney, as vice president, had a power greater than many presidents.

Rupert Cornwell wrote this obituary prior to his death in 2017