Mike Newell was looking for an actor in her mid-twenties who could expose the interior life of a working-class woman who shot dead her upper-class lover. The filmmaker saw hundreds of women of the right age and type – yet wasn’t satisfied. Then someone recommended a complete unknown doing rep theatre in Lancaster. “She came into the casting director’s office in the middle of Soho just as a police car went past,” Newell recalls of their first meeting. “She said, ‘Oh, I like a bit of trouble,’ and danced over to the window. I thought, ‘Well, that’s good news… because you’re it.’”

The year was 1984, and the troublemaker in question was Miranda Richardson, who was auditioning for her first feature-film role. “His story is probably better,” deadpans Richardson, who recalls this first interaction less flamboyantly. “Hearing the noise on the street is true, but I was also quite pissed off. I’d come all the way down from Lancaster on a train, and had to get back to do a theatre show that night. I hadn’t met him. I’d only met the casting woman until, at the end of the audition, this shape came in and rooted in the fridge in the back room.” The shape was, of course, Newell, and – after a second audition – the 26-year-old Richardson was cast in his Dance with a Stranger as Ruth Ellis, the last woman in the UK to be sentenced to death.

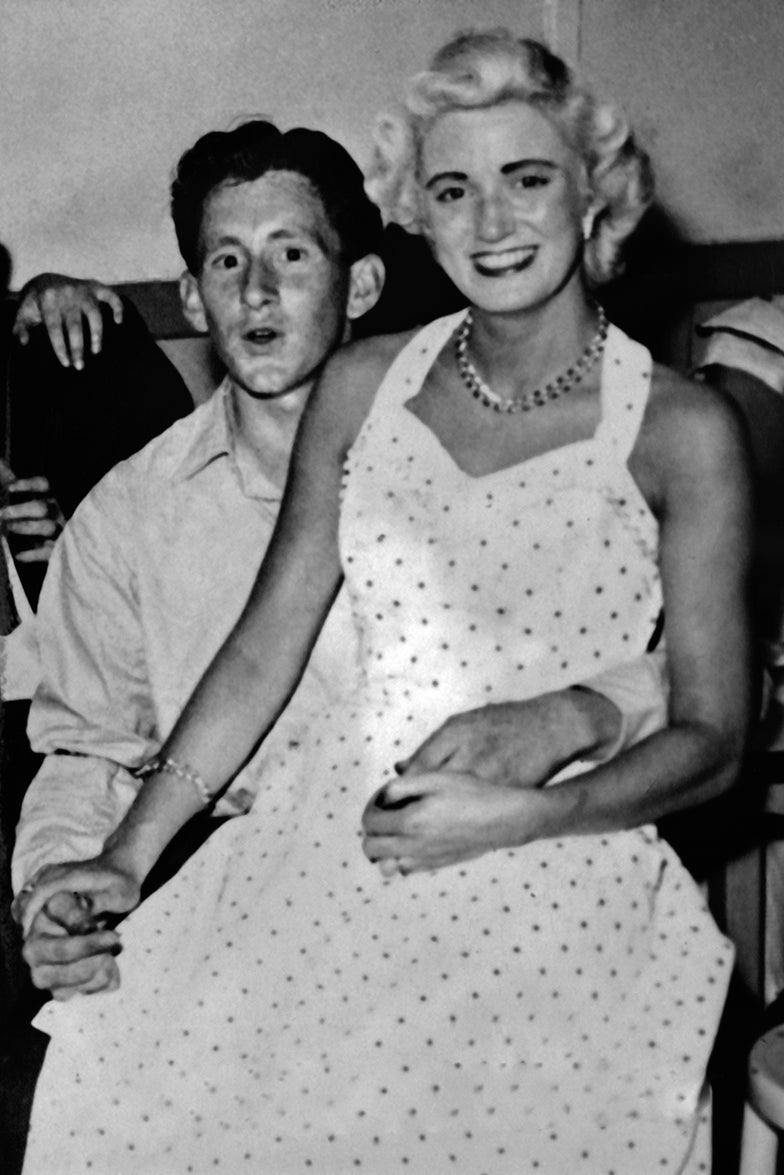

In 1955, when Ellis – a platinum-blonde, 28-year-old nightclub manager and mother of two – shot dead her abusive lover, David Blakely, outside The Magdala Tavern in Hampstead, the mythologising began instantly. The topline details were tabloid heaven (“I INTENDED TO KILL HIM” screamed the Dundee Courier), but a more serious and critical undercurrent has persisted due to Ellis’s fate. A jury took 23 minutes to find her guilty of murder, ignoring the mitigating factors – including Blakely’s violence against her and a miscarriage that followed – that would have lessened the charge to manslaughter and saved Ruth’s life.

Ellis has achieved a type of cultural immortality, with legal campaigners and concerned artists seeking to reclaim her from the patriarchal forces that condemned her to death. This year brought a miniseries, A Cruel Love, adapted from the 2012 book A Fine Day for a Hanging by Carol Ann Lee. It is also the 40th anniversary of Dance with a Stranger – which won the Award of the Youth at the 1985 Cannes Film Festival. At the time of its theatrical release, critic Roger Ebert awarded full marks for “a film of astonishing performances and moody atmospheric visuals”, while Time Out magazine put it in the same bracket as the dark social parables by the German New Wave iconoclast Rainer Werner Fassbinder. “It’s shot, designed and acted with an imaginative grasp that puts it straight into the international class,” the magazine wrote. Even publications not fully sold on the film bowed down before Richardson’s performance, with Vanity Fair wondering whether we were “witnessing the emergence of the next Maggie Smith or Vanessa Redgrave.”

Newell, whose chameleonic career has gone on to include Four Weddings and a Funeral, Donnie Brasco and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, is 83 and full of bonhomie when we talk over Zoom during the shoot for his next film. “Very good, my dear, I have all the time you need. Simply ask your questions. Don’t feel you have to move on until I have properly answered them!”

Dance with a Stranger has folkloric origins of its own. How it came to Newell, he admits, is brewed partly in reality and partly in his own dramatic imagination. While producer Roger Randall-Cutler was on holiday in Gozo, an island in Malta, he met a man in a bar who introduced himself as Ruth Ellis’s solicitor. As Newell tells it, he was from a small, high-street firm. “He wasn’t powerful, so when it got to court, he was talked down to – belittled – by these great big powerful, rich, posh QCs. He believed that he had not done right by Ruth, so he had retired and was now drinking himself to death.”

At the time, Newell was an established TV director and a relative newcomer to filmmaking, with only the supernatural horror The Awakening and the thriller Bad Blood under his belt. For a third feature, his agent offered him a choice between a spy movie and Dance with a Stranger – he chose the latter in part because of its socially acute screenplay by Shelagh Delaney, famed for the play A Taste of Honey, and partly because the character study it contained struck very close to home.

“I knew the woman,” says Newell. “The things in the world that bullied Ruth into submission were the things bullying my mother into submission.” Although his mother was middle-class rather than working-class like Ruth, and although she was a housewife rather than a nude model turned escort turned nightclub hostess, her potential, like that of Ruth, was winnowed down by the gender roles that prevailed at the time.

We meet Ruth as an aspiring working-class woman intent on improving life for her son, and on guard against any sharks tempted to chew on a young, Marilyn-esque blonde in a social job in 1950s London. When her “friend” Desmond (a creepy, poker-faced Ian Holm – awarded Best Supporting Actor by the Boston Society of Film Critics) brings wealthy racing driver David to her club, the whole film depends on us understanding why she wants to risk her independence to dance with this stranger.

The search for an actor who could make David alluring for all his destructive entitlement while offering a name with audience appeal led to Rupert Everett. He’d shot to prominence a few years earlier in the role of a gay public schoolboy turned spy in the play Another Country, which was adapted into a film in 1984. What’s more, he was raw. “Like all good actors, it’s as if he had a couple of skins too few,” says Newell. “His inner self, emotions and tensions were on the surface, and he was prepared to put them out and leave them out.”

Everett’s performance holds both charm and repulsion. He is irredeemably cruel and, seconds later, a lost boy who needs Ruth. When they first meet in her club, he is rude and she is sure to give it back; later, when he is forlorn and wants to take her home, the camera is held rapt by his delicate eyelashes. There is no attempt to create distance between the auteurial perspective and Ruth – her psychology becomes our reality.

Following five years of rep theatre and a tiny bit of TV, Richardson was now carrying a feature film weighted with real lives, playing a role that required her to show every dimension of a person as they spin out of control. “It’s a responsibility, of course, playing somebody who is known to people,” says Richardson. “I don’t think I realised at the time, because I was just playing the story. I was flying blind, learning as I went, so there was a lot of instinct.”

She’s “not brilliant”, even now, at asking questions during filming, she says. Back then, not wanting “to appear stupid”, she hardly queried a thing and ended up burnt out. “The schedule was heavy-duty, but I didn’t know any better, so I was just trying to keep up. It did become enjoyable, but I didn’t look after myself particularly well.”

The volatile chemistry between her and Everett – sometimes imbued with cruelty, sometimes with tenderness – flourishes in intimate moments that include sex scenes and a lovely one of her shaving him in the bath. This was an era before intimacy coordinators. “Mike didn’t make it awkward – it was just another work day,” she remembers. “He was extremely close to us. He wasn’t pushing bits of us around or anything, he was just in the room, which actually I was very comforted by if I needed comforting. I remember being quite practical about it.”

Her advice to new actors is to talk these scenes through in advance. “Things like that slightly loom. Intimacy coordinators, generally speaking, are a good idea. But you don’t want to over-talk something, you don’t want to kill it.”

Looking back on her formidable performance right out of the gates, Richardson is understated. “I think I did a good job.” Newell is more fulsome. “She clambered inside the character,” he says. “And I have loved her ever since.” Not only did Dance with a Stranger launch Richardson’s highly varied screen career – which went on to include Blackadder and film collaborations with Stephen Spielberg, Robert Altman, Neil Jordan, Tim Burton and Louis Malle – it created a decades-long friendship and partnership with Newell. When we speak, they are shooting their fourth film together, a period drama about Wallis Simpson starring Joan Collins and Isabella Rossellini called The Bitter End.

Forty years after it was released, and 70 years after Ruth shot David, Dance with a Stranger still resonates. Why? There is the grisly stuff, of course. The Magdala Tavern in Hampstead has “bullet holes” outside, even if these were drilled into the wall by a former landlady to add value to the pub in murder-mystery tours. As Richardson says, “Ruth’s sort of an icon, like Billy the Kid, and she’s not around to defend herself.”

Unlike non-fiction artifacts – such as the 2018 investigative BBC documentary The Ruth Ellis Files: A Very British Crime Story, or books by Ruth’s daughter Georgina as well as her hangman, Albert Pierrepoint – Dance with a Stranger is not purely governed by factual impulses. It balances being the true story of a real person (Newell wanted to fill in the gaps in the jury’s considerations by “offering a set of motivations for what she did”) with being a bigger, almost archetypal illustration of a primal female fear – that dancing with a stranger will end in violence.

The film stops short of showing Ruth’s death, and ends on a note she wrote from prison to David’s parents: “I have always loved your son, and I will die loving him.” Yet as the scholar bell hooks wrote, “Love and abuse cannot coexist.”

Our legal culture is in the foothills of understanding the psychological elements of abusive relationships, with terms like “diminished responsibility” and “coercive control” emerging from the case of Sally Challen and the activism of her son David. In 2019, Challen – who served nine years and four months in jail for killing her husband after decades of emotional abuse – walked free, after her murder conviction was quashed and her manslaughter plea accepted.

She had this to say post-release: “Many other women who are victims of abuse, as I was, are in prison today serving life sentences. They should not be serving sentences for murder but for manslaughter.”

Amid an understanding that she did not live to see, Ruth’s story takes on increasingly tragic and cautionary dimensions. Dance with a Stranger, meanwhile, distils something about patriarchal violence and British classism that rings true to this day.