A huge event today could have a major impact on national politics—and it might not be the one you have in mind.

While a judge arraigns Donald Trump in New York City, voters in Chicago will be rendering their own verdict on who should lead the nation’s third-largest city: Paul Vallas, a 69-year-old former city-budget director and the former CEO of Chicago Public Schools, or Brandon Johnson, a 47-year-old county commissioner, former teacher, and longtime paid organizer for the city’s most progressive political force, the Chicago Teachers Union. The outcome could have meaning well beyond the shores of Lake Michigan, offering an indication of where voters—Democrats in particular—are leaning on the issues of crime, policing, and race.

For Chicagoans, though, this election is about more than augurings for the nation. Crime and public safety are, far and away, the issues of greatest voter concern here. Although shootings and homicides are down from a year ago, Chicago’s homicide rate remains five times higher than New York City’s and 2.5 times higher than Los Angeles’s. In 2022, crime in Chicago rose in almost every other major category, including robbery, burglary, theft, and motor-vehicle theft. Those numbers and the pervasive sense of unease about public safety had a lot to do with the defeat of incumbent Mayor Lori Lightfoot in the city’s nonpartisan primary in February.

Even great cities are fragile—one furor or fire away from disaster. In the half century that I’ve called Chicago home, Carl Sandburg’s City of the Big Shoulders has been fortunate to produce a succession of larger-than-life leaders when they were most needed. It’s not clear if either candidate in Tuesday’s runoff is that leader. Chicagoans face an imperfect choice between an aging, white technocrat who believes the answer is more, and more effective, policing, and a relatively inexperienced young progressive, a Black man, whose vision for combatting crime and violence goes to conquering poverty and racial inequity.

The former, Vallas, is a charismatically challenged data nerd with roots in the city’s white bungalow communities and close ties to its conservative police union. Vallas has pitched almost his entire campaign around public safety, promising to add 1,800 police officers and promote “proactive policing” to confront “an utter breakdown of law and order.” He has also said that police have been “handcuffed” in pursuing crime. That phrase worries some Chicagoans who recall incidents such as the 2014 murder of Laquan McDonald, a teenager shot 16 times in the back while trying to flee Chicago police, which led to a Justice Department investigation and a consent decree with the Illinois attorney general requiring the Chicago police to make reforms.

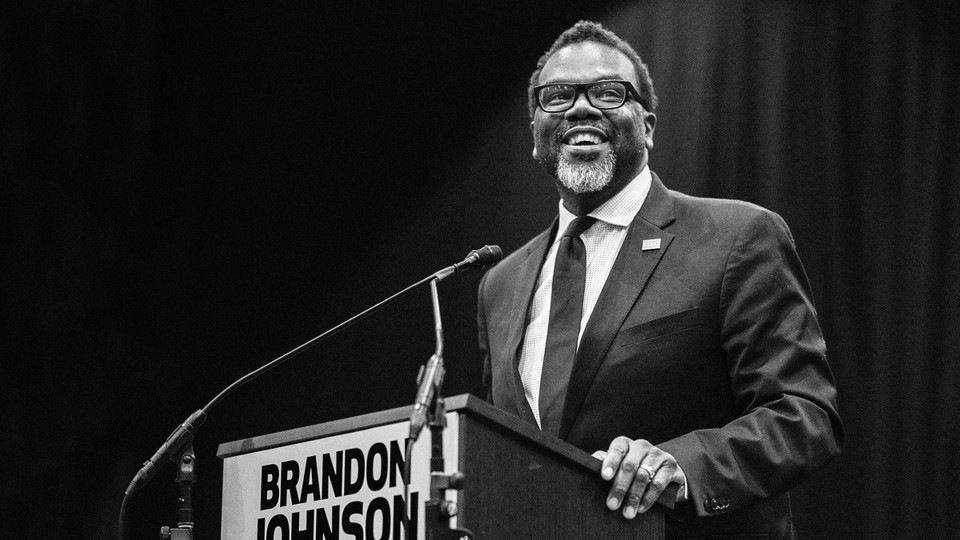

Johnson, more comfortable in the spotlight than Vallas, began the race last fall with little name recognition in much of the city. But with the financial backing of the CTU, he finished strong enough to squeeze Lightfoot out of the runoff, largely by rallying white voters behind his progressive platform. Johnson has pledged $800 million in new taxes on large businesses and the wealthy to make significant investments in housing, mental-health services, and economic development in impoverished communities on the city’s South and West Sides.

Vallas, who has the backing of the city’s business community, has been more circumspect about tax increases. Johnson has attacked Vallas as a crypto-Republican and an opponent of abortion rights (both of which Vallas denies). Vallas, in turn, has questioned Johnson’s experience and attacked him for owing thousands of dollars in city fees and fines. (City officials recently confirmed that Johnson has now paid off the debts.) And whereas Johnson is a bitter opponent of school vouchers and charter schools, Vallas, who has run public-school systems in four cities, favors them.

But the biggest line between the two has come over the issue of public safety and policing. Johnson has pledged to immediately train and promote 200 officers to the rank of detective to help improve the city’s dismal 30 percent clearance rate of unsolved homicides and other major crimes. But he has resisted Vallas’s call for more police, noting, correctly, that even with its current police manpower—down 1,700 officers since Lightfoot took office—Chicago still has more police per capita than New York, Los Angeles, and almost every other big city in America. Given that, Johnson argues, the city should approach its public-safety challenges with other strategies, namely by addressing the historic resource and investment discrepancies between predominantly white communities and communities of color.

Vallas has pummeled Johnson relentlessly for comments he made following George Floyd’s murder, when Johnson pushed for a county-board resolution calling for a shifting of funds from policing and incarceration to human services. In a radio interview in December 2020, Johnson was asked about a comment by former President Barack Obama, for whom I once worked, who had called “Defund the police” a “snappy” slogan. “I don’t look at it as a slogan,” Johnson said then. “It’s an actual, real political goal.”

John Catanzara, the outspoken and divisive head of Chicago’s local Fraternal Order of Police and a Vallas supporter, told The New York Times that there would be “blood in the streets” if Johnson wins, because as many as 1,000 current police officers would immediately leave the force. It was an ugly and incendiary comment. Still, Johnson’s past statement on defunding the police and his current policy proposals have caused cooler heads than Catanzara to worry about Johnson’s ability to effectively lead and motivate the police as mayor. Arne Duncan, Obama’s former education secretary who leads a violence-intervention program in the city, recently endorsed Vallas. “He’s best positioned to try to lead the change that’s needed in the Chicago Police Department,” Duncan told Politico. “Paul has credibility, and he has trust.”

Vallas, who has family ties to policing and helped negotiate the last city contract on behalf of the FOP, argues that his relationship with the rank and file would revive flagging morale and encourage retired, seasoned officers to return to fill some of the new detective slots he plans to create. He promises to offer more rigorous policing without violating the consent decree against excessive force that the city signed after the McDonald murder. But a major test would come if new cases of excessive force by police emerged on his watch.

Johnson hopes that the endorsement of two national progressive icons, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, will help stir turnout among younger voters in the runoff. If Johnson wins, he will join them as a luminary of the left, lauded for his new public-safety paradigm. But he will also become a ready target for Republicans, who have made urban crime and the largely exaggerated specter of “defunding the police” a major focus of their attack on Democrats across the country. A Vallas victory, much like that of Mayor Eric Adams of New York City, would help Democrats rebuff such attacks in 2024.

The choice for Chicago voters is not exactly clear. Johnson’s aspirational vision of fighting crime by combatting injustice is more hopeful than the well-trod path of simply fine-tuning policing, but his is a long-term strategy for an immediate crisis. Vallas’s policing-heavy solution is not enough to end an epidemic that has deeper roots, but it is necessary. Although Johnson’s idealism is appealing, he has never run anything larger than a classroom and too often devolves into progressive sloganeering. Vallas’s long experience in government, however mixed his success, is reassuring. Yet, nearing 70, he seems more a caretaker, subsumed in a tangle of numbers, than the visionary the city requires.

We need a healthy dose of what each man offers but can choose only one, knowing that neither has the whole package. Chicagoans want a change. The rest of the country is watching to see which direction the city goes. But it’s possible that neither candidate can provide the transformation the city needs.