"The Americans said, 'What the fuck are you guys doing?' You're supposed to be Bush, and now you're trying to be Devo!"

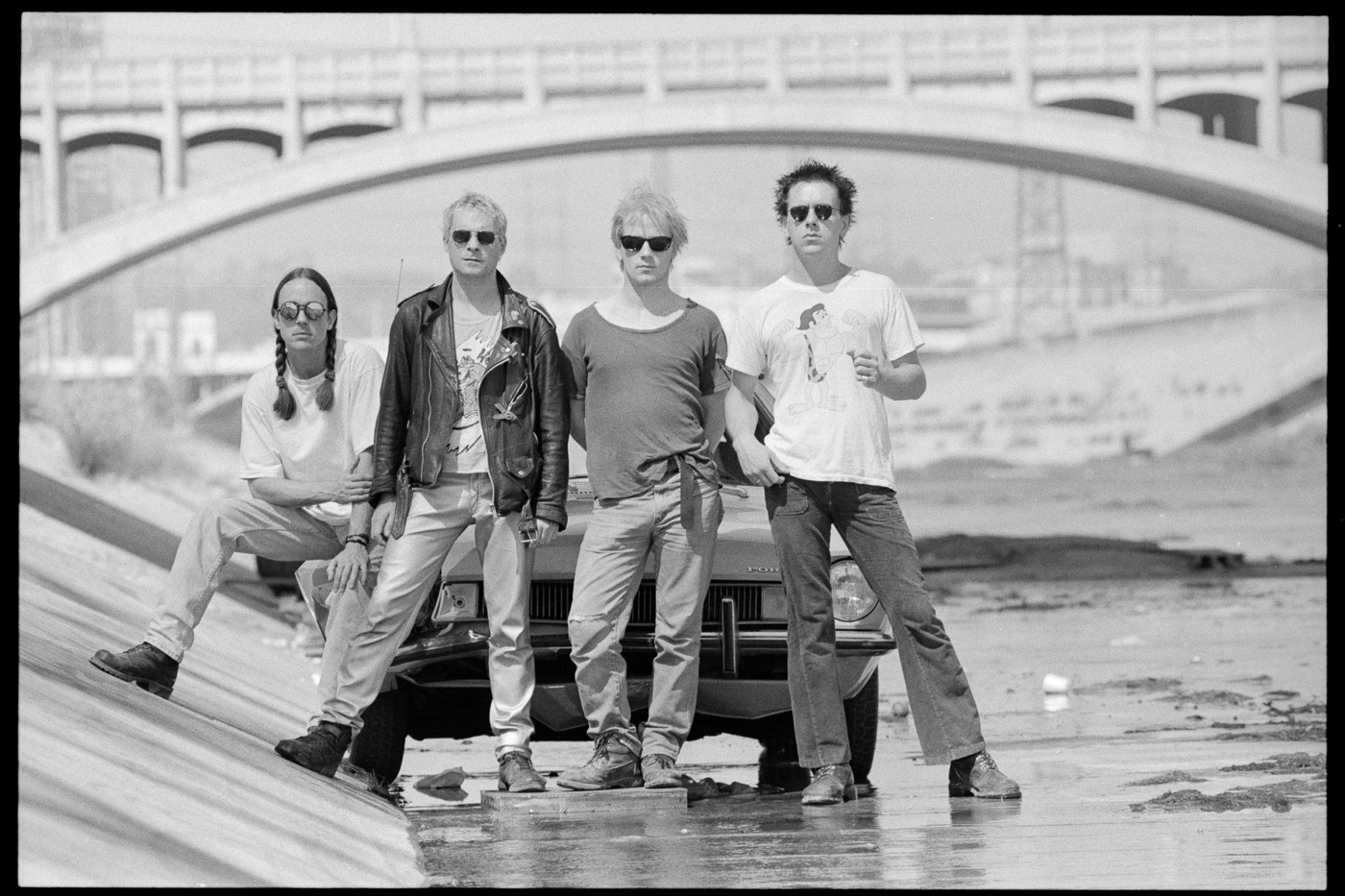

Garret 'Jacknife' Lee has precious few regrets about failing to become a rock star. One of the world's most in-demand studio technicians, his star-studded CV includes producer credits on albums by U2, R.E.M. and Snow Patrol, co-writing credits on songs by Taylor Swift, One Direction and Robbie Williams, plus remixes for Radiohead, Pink, Bjork, Missy Elliott... oh, and The Beatles and Elvis Presley. So you can understand why the Dubliner isn't too troubled by the fact that his former band Compulsion - rounded out by Josephmary (vocals), Sid Rainey (bass), and Jan Alkema (drums) - didn't set the world on fire.

Frankly though, this was the humanity's loss, as is evidenced by the forthcoming re-release of the Dublin punk quartet's two albums, 1994's Comforter and 1996's fabulously cynical, raging The Future Is Medium, the latter genuinely one of the most under-rated albums of the decade.

Back in 1996, when I was a wide-eyed, naive innocent newly resident in London, Garret Lee invited me to join him for a couple of pints in Camden after I'd interviewed his band for a feature in Kerrang! magazine, an act of kindness I've never forgotten. Back then he came across as incredibly sharp, self-aware, perceptive and utterly unimpressed by music industry hype and bullshit: the passing decades have only made him more so.

I wanted to start by taking you back to early '90s Dublin: what do you remember of the music scene in the city as Compulsion were starting?

"Well, the short answer here is that we weren't really in Dublin in the '90s: Compulsion were in London, in our own world of our own making.

"But before Compulsion I was in another band called Thee Amazing, Colossal Men. And there were two iterations of that. The first one, I was a kid, 15 or 16, and we were a garage punk band, playing music like The Seeds, or The Chocolate Watchband, or The Misunderstood. That was a fun band, and kinda cool, but then we started getting serious, and thought, Oh, we can get a record deal! There was a lot of post-U2 stuff happening in Dublin, with A&R men coming over to sign 'The Big Music'. We were still in our The Who Live At Leeds mentality, but we got the scent of massive success. The thing is though, when Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil, he still made good music: we didn't, we made shit music.

"So we'd wanted to sound like The Who Live At Leeds, and ended up working with a producer who had made a really bad Roger Daltrey solo record, a guy called Alan Shacklock. We went into it wide- eyed, but willing to be bent. And I don't know what the fuck happened, but we made a record (1990's Totale) that we didn't play on for months, which ended up sounding like Cutting Crew. And we thought, Fuck that! By this point our trajectory had moved on from Live At Leeds to Neil Young and Crazy Horse's Zuma, so then we thought, Okay, who made Zuma? The engineer on that was this guy called Niko Bolas, so we went to LA - where I met my lovely wife - and recorded an album with him. But the label were expecting another Cutting Crew-style record, and instead, they got this Zuma thing, so they just dropped us. And we thought, Well, fuck this, let's go back to when we were having fun. Thee Amazing Colossal Men should have been the MC5, but we ended up being T'Pau. Fuck knows how, but we did it. So that was a lesson we learned. And that was the beginning of Compulsion.

Was London a better fit for Compulsion?

"Well, we were fighting against everybody in Dublin. We were troublemakers. They were all about The Waterboys there, and we were taking a lot of acid at the time, and causing trouble wherever we went, getting barred from most places. And then we took that fight with us to London, because that's just who we were.

"In London we were the worst party guests you could possibly ever have: we got invited to the party, we'd go, and then we'd just talk about how shit it is. When everybody was having a great time on Ecstasy, we were taking speed, the wrong fucking drug for the time. Everyone else was having this big love-in, and we're there railing against everything. Life would have been so much better, and we may have lasted longer had we taken Ecstasy. I did it once, and thought, Why don't we take this all the time? But it was already too late."

You're great friends with U2 now, but for Compulsion back then, given the massive shadow they cast over every Irish band, were they an inspiration or would they have been the enemy in your eyes?

"I always liked them. Achtung Baby was an astonishing record, distilling My Bloody Valentine and Happy Mondays and all this shit into a record that sounded super fresh. But in Dublin, it was hard to fight your way out of their shadow. It must have been like being a band in Liverpool after The Beatles. So it was frustrating. And it was more frustrating because they were brilliant.

Our attitude was, sabotage yourself, wish destruction on those you consider your competitors. it wasn't a healthy mind set

"The things that Compulsion didn't possess were very evident in U2. We had a very Camden indie sabotaging attitude - sabotage yourself, wish destruction on those you consider your competitors - and it wasn't a healthy mind set. U2 just seemed to want to be the best, whereas we were just trying to be cool, which meant that we weren't trying to be good.

"That was what was wrong with that whole scene of Elastica and all that: there was just so much fucking energy expended trying to be cool. Punk was interesting in that it reset things, but the NME and Melody Maker and all those fucking eejits that wrote for them never got over it. There was the Brian Eno/Radiohead art school scene too, but if you weren't educated, it was just, Be cool. And that became the currency of that whole period. And it's a real shame, because none of those bands have lasted the distance. We lost incredible talent and possibility, because there was so much effort trying to be cool. I think Blur maybe transcended that, because they got into the American thing, and didn't have that sensibility or those restrictions.

"But that was the trope at the time, and U2 just didn't have it. They were always striving to be fresh and unique and put their own spin on music: they made the road map for how to be innovative and then go beyond. So I was aware of them and somewhat jealous, I think, if I was being honest. We were always trying to make a point rather than make a good record."

What sort of ambitions did you personally have circa Comforter?

"None. That record was basically what was left over from the EPs. We had Mall Monarchy, so we knew that was good, although even that irks me now, it's just so primary colouring and so basic, and Basket Case even more so.

"But we had no ambition. We didn't actually record an album, we just recorded loads of things and put whatever we recorded out, and then we had these songs left over. We were doing our own label - I think we were pressing 500 pieces of vinyl at a time - but then One Little Indian picked it up, and then people started sniffing around. We had a few singles of the week in the weeklies [NME, Sounds, Melody Maker] and, at the time, that meant something in the States. And then everybody was hunting for the next Nirvana or whatever. We were on the dole [unemployed] at the time, so had no money, so when somebody said, 'We can give you 60 grand for the record', that was life changing money.

"So suddenly we got very ambitious, and competitive. And the drugs and the booze didn't really help. The Americans were saying, 'You guys could be a huge success, and you don't have to change a thing.' That should have set the alarm bells ringing. We ended up signing to Elektra, and that kind of fucked up, then we went to Interscope.

"I think we had set our sights way higher than we should have: had we just stayed where we were happy, we probably would have lasted. We probably reached the peak of where we should have reached, and we should have been happy there, rather than thinking we were better than we were, and then being disappointed. Because then that disappointment became most of our energy. And when we got to the second record, I didn't really give a fuck about the whole 'Breaking America' stuff."

At the time, it didn't seem like Compulsion fitted in anywhere. In the US there was the post- grunge scene, and the Green Day/Offspring punk explosion, and in the UK, there was the New Wave of New Wave, and then Britpop, and you didn't fit into any of those movements. So was there anyone that you identified with?

"We liked Done Lying Down, and we liked Pavement at the time. But yeah we were always on the periphery of all those scenes. But I'm sure that if you travel another 50 years into the future and listen back to all that music, it probably all sounds exactly the same! I hadn't listened to our records in a while, mainly out of the fear that they were shit and that listening back would have confirmed some doubts that I had about myself at the time, ie, that I fucked up, and I wasted my time. But when I listened I was quite surprised by them. Then decided to listen to some of the other bands that were around at the time... and I feel like we were better than a lot of them."

We were raging fucking lunatics with amphetamines, railing against the world

For many indie music fans, the Britpop era was a golden age. For you, not so much.

No. It was such a nostalgic look back at an older England, like what people saw as 'glory days' for Britain, the 1966 World Cup, The Kinks, the Small Faces, looking back to when Britain had colonies and they didn't fucking complain. And Britpop was the Make America Great Again of its day, all that Rule Britannia shit. I was pissed off, at that kind of Britpop xenophobic shite, it was misogynist, it was Loaded magazine, it was TFI Friday, it was just fucking lads asking for tits out. It was horrible, and we hated it.

"We were a bit right on, with a very kind of Marxist outlook on things, and so that was fuelling our anger. We were raging fucking lunatics with amphetamines, railing against the world. So there was no way we were going to join any of those groups, because none of it appealed. Our attitude at the time was 'Fuck England, look to Dusseldorf'. And with the American post-grunge/punk thing, I think when we were told we might fit in, we just ran away from it."

The idea of doing The Future Is Medium, a concept record critiquing '90s Britain from a Marxist perspective, at the height of Britpop was a bold move. Perhaps a bit too clever for the time?

"Well, we were seen by some as these wind-up, dumb arseholes, four Sid Viciouses, and we did play up to that a bit, because it was very entertaining for us. But we weren't supposed to do a concept record, that's for sure. And the follow up, The Futurist Medium, which was a reimagining of that record produced by [Tortoise's] John Entire, and Howie B and people like that, that's kind of where I was going. And that's when the band were thinking, 'What the fuck are you on?' I probably was pushing them too far. And at that stage we were then fighting among ourselves more than against everybody else."

When you listen back to The Future Is Medium now, is there a certain amount of pride, or is all you hear the things that you would do differently in 2025?

"I think it's great. I honestly wish a lot of bands might sound like that now. There's a few interesting bands now, but I think too many bands want to be liked. Fontaines [D.C.] I get it, but I much prefer stuff like Gilla Band - a fucking incredible band - or that new band from New York, YHWH Nailgun. People talk about why don't bands exist anymore? It's because you just want to be liked, and you've got nice fucking shoes and you just want to pay your mortgage.

"New Labour was a bad thing for bands and music: you could actually design your way to success. So I listened to our record, and I love it. I was so disappointed that it just never connected at all, couldn't understand it. So, by its failure. I just thought, Fuck it. I thought, that's a good record, so there is no point in even working on another one. Because the only thing we were going to do is go more extreme, and less people will like it, and it's a lot of energy, and I had to drag so many other people with me.

"The label lost faith, and they had spent a lot of money doing these remixes - there was a 12 inch for every every fucking remix. And by 1997 interscope thought, 'We've already made our money from Bush and No Doubt, we don't need Europeans'. Meanwhile, in the UK, Oasis were killing it, and Compulsion were surplus to requirements. We split in '97, and the fact that The Future Is Medium failed like it did hurt for about 20 years."

Were you surprised then that One Little Independent are doing these reissues?

"I was, yeah. Rick Lennox, who was our A&R at the time, and signed us, we had gotten into this group chat, so I think it was a lot of encouraging each other. Somebody at Universal once mentioned 'If you ever want to put out that record, we could reissue it' and I thought, That's interesting. The Future Is Medium wasn't on any of the streaming services, so I put it up myself a few years ago. Because One Little Independent didn't, they didn't give a shit about it, and we weren't even on their website, it was like, we'd been canceled. But Rick went to them and asked about it, and they said, 'Sure, we'd love to do it.' So here they are, and people can actually hear them again and make up their own minds."

The reissues of Compulsion's Comforter and The Future Is Medium will be released on One Little Independent on May 2.