Bolivians are going to the polls in an election that could mark a shift to the right and the end of nearly 20 years of rule by the leftist Movimiento al Socialismo (Mas).

The party, which came to power with the first election of Evo Morales in 2005, risks losing its legal status if it fails to reach 3% of the vote – a threshold it has not hit in polls.

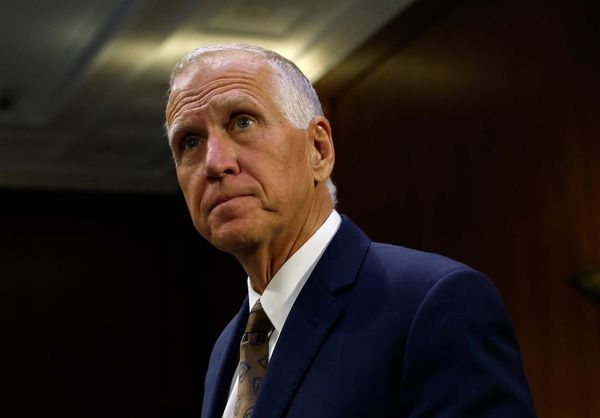

Two opposition candidates for the presidency are virtually tied: the centre-right business tycoon and former planning minister Samuel Doria Medina, followed closely by the rightwing former president Jorge “Tuto” Quiroga.

The incumbent president, Luis Arce, 61, deeply unpopular amid the country’s worst economic crisis in four decades, decided not to run.

A finance minister under Morales for 14 years, Arce took control of Mas gradually in recent years. He nominated his 36-year-old minister of government, Eduardo del Castillo, who has been polling at about 2%, to run for president.

Morales, 65, is the target of an arrest warrant for allegedly fathering a child with a 15-year-old and has been entrenched in a coca-growing region of central Bolivia since October in an attempt to run for office again.

After registering with another party but being barred by constitutional and electoral court rulings, Bolivia’s first Indigenous president called protests that escalated into deadly clashes with police.

He is urging supporters to cast null votes on Sunday, claiming that if these outnumber the leading candidate’s tally, it would mean he had won.

Carlos Toranzo, a political analyst, said: “Before Morales’s call, null votes were about 10%; now they’re 12%. Even if it rises, I doubt it will go much higher – and null votes have many causes, not just him.”

As polls have historically been unreliable in Bolivia, and many voters remain undecided, Toranzo said there was “a small chance” that a third person could make it to a potential runoff against Doria Medina or Quiroga – the 36-year-old senator Andrónico Rodríguez.

The highest-polling figure on the left, placing between third and fifth, Rodríguez was once seen as Morales’s natural heir due to his Indigenous roots and leadership in the coca growers’ union, but was called a traitor for launching his own candidacy.

A longtime Mas member, the senator chose to leave the party and run with the leftwing coalition Alianza Popular – another sign of how fragmented the left’s vote has become.

Enrique Mamani, the leader of the Aymara Indigenous organisation Ponchos Rojos, said he would back the senator, calling Morales the real traitor.

“Those calling for null votes are a handful of traitors to the struggle of our grandparents, who shed their blood and gave their lives so that one day we could have this right to vote,” he said.

On Sunday, as Rodríguez cast his vote in Entre Ríos, in the Cochabamba tropics – a Morales stronghold in central Bolivia – he was booed by some voters, who threw stones and glass bottles at the candidate. A clash broke out between the senator’s supporters and opponents, and he left the scene reportedly unharmed.

Despite the incident, the president of the electoral court, Óscar Hassenteufel, said the elections are, overall, taking place in an atmosphere of “considerable calm”.

About 7.9 million Bolivians are eligible to vote, and preliminary results are due at 9pm local time.

The central issue of the campaign is the economic crisis, which analysts consider the worst since the hyperinflation of 1985, with shortages of dollars and fuel, long queues and soaring inflation.

“It’s a very difficult moment but I hope that after this vote things can improve,” said Silvia Marca, 42, after casting her ballot in La Paz. She runs a small street business and said trade had dropped sharply in recent months. “I hope the right wins,” she added.

If no candidate secures more than 50% of the vote, or at least 40% with a 10-point lead over the runner-up, an unprecedented second round will take place on 19 October.

For the analyst Toranzo, one thing is certain: Mas will leave power, although he said it will be “difficult for them to hand it over, because they have held it for 20 years with near-absolute control of parliament, the judiciary and the electoral authority”.

Arce told the Guardian he would respect the result if the right won. Although acknowledging that his government was unpopular, he placed much of the blame for the crisis and Mas’s decline on his former mentor, Morales, whose parliamentary allies, he said, had “sabotaged and boycotted all our laws”.

“As Fidel Castro wrote in his book, history will absolve us, because in the long run the people will understand everything we had to endure,” Arce said. “I’m sure the population will miss us afterwards.”

On a cold Sunday morning in Bolivia’s capital, the president was greeted with chants of his nickname “Lucho” by about a dozen supporters as he arrived to cast his ballot. A voter criticised Arce and was then harassed by the group.

“I only said to him: ‘What happened to the country, president?’ and those people started to attack me. I bet they are government employees,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified. “I know I’m not the only one in this country who is fed up with this government. We’re all frustrated that our money doesn’t stretch.”

In Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country’s commercial hub, Arce’s candidate was booed. According to the newspaper El Deber, Del Castillo reportedly skipped the queue and was told by a woman: “Get to the back. Line up like we do at the petrol stations.”