Bill Walton won two California Interscholastic Federation championships with Helix High School, led the UCLA Bruins to an astonishing record 88 straight wins and two NCAA championships, won an NBA title with the Portland Trail Blazers and another with the Boston Celtics. But in the four-part ESPN “30 for 30” documentary series “The Luckiest Guy in the World,” Walton said the game that stands out above all others for him was a first-round contest between the Trail Blazers and the Chicago Bulls in 1977 at the old Madhouse on Madison.

“I loved playing in Chicago,” says Walton. “That’s what you live for. That was the single most exciting basketball game I’ve ever played in my life. … The fans, the atmosphere, the culture, the battle, so many things went down.”

There were dozens of lead changes in an intense battle, not to mention a brawl that broke out on the floor, but in the end, it was the Bulls winning 107-104. The Blazers would go on to defeat the Bulls in the deciding game in Portland on the way to their one and only NBA championship — but it’s a testament to Walton’s unique and passionate and big-picture view that would he choose a mostly forgotten, hard-fought, first-round playoff loss as the most memorable game of his storied career.

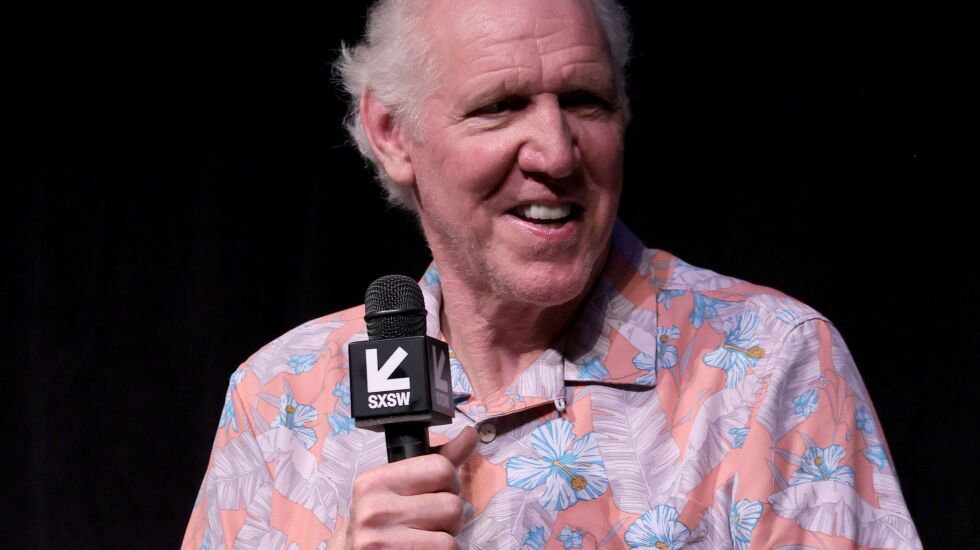

Directed by Steve James (“Hoop Dreams,” “The Interrupters”) and brimming with life and color and positivity, much of it set to a soundtrack filled with tunes by Walton’s beloved Grateful Dead, “The Luckiest Guy in the World” is worthy of the four-part treatment, given the number of memorable chapters in the 70-year-old Walton’s life. The story runs from his days as a high school phenom to his legendary run with UCLA to his social activism to his injury-riddled Hall of Fame career as a pro to his current status as one of the most polarizing basketball commentators in the world — an aging hippie who will alternately delight and infuriate with seemingly random tangents, observations and non-sequiturs.

He’s a giant of a man with a giant of a life, and while there have been numerous and nearly crippling setbacks, Walton keeps insisting, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world.”

In director James’ expert hands, the series smoothly toggles back and forth along Walton’s timeline. Walton speaks in glowing terms of his upbringing in La Mesa, California, lauding his parents for being supportive and loving, and noting that his older brother Bruce, a behemoth of a young man who played college football for UCLA and was an offensive lineman for the Dallas Cowboys, was always there to protect Bill when he was a skinny, socially awkward kid. Younger-generation fans who know Walton primarily from his non-stop rambling on TV might be surprised to learn he had a serious stuttering problem that extended well into his days as an NBA star — leading many to think he was a difficult interview and had a distant personality, when in reality it was a major challenge just to express himself. (With the help of Hall of Fame broadcaster Marty Glickman, Walton eventually found a way to speak nearly entirely free of stuttering.)

One of the remarkable things about “The Luckiest Guy in the World” is how his infectious enthusiasm for the game of basketball and the joys of life seems to have rubbed off on so many people. His four sons talk of how they feel closer than ever to their father, who has made up for all those years he spent traveling by being a constant presence in their lives. NBA legends Julius Erving, Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, Robert Parish and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar speak in glowing terms of Walton’s competitiveness and talent and team-first approach to the game. The Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir talks about the band’s unique friendship with its tallest fan.

When Walton in present day visits some kids on the playground and offers a few tips (while lamenting that he can’t jump an inch off the ground anymore due to all his injuries), they call him “Mr. Walton” and he tells him it’s just “Bill.” He’s just Bill.

Not that Walton’s life has been a smooth skate. Throughout his professional career, he was sidelined by a horrific series of injuries, mostly to his feet, enduring dozens of surgeries and receiving sometimes questionable medical treatment even as some speculated about his toughness. There’s a moment of true tension in the documentary when Walton’s unseen interviewer, presumably James, notes that Walton was always paid even when he was sidelined with injuries, and Walton bristles at the notion that this was a good deal for him.

One of my favorite scenes in “The Luckiest Guy in the World” is when Walton’s wife, Lori, takes us on a tour of their home, which is filled with Grateful Dead memorabilia and includes a teepee on the property. It’s EXACTLY the kind of house you’d expect Bill Walton to be living in, and as he hobbles around with a perpetual smile on his face, often opening his arms as if to embrace the sky and the sun and the air and life, you believe him when he once again says he’s the luckiest guy in the world. The world is certainly a more interesting place with Walton in it.