Tasuku Honjo, a distinguished professor at Kyoto University who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine last year, has been at odds over patent compensation with Ono Pharmaceutical Co., which developed the cancer immunotherapy drug Opdivo based on Honjo's research. To prevent similar disputes, universities and research institutions face the pressing task of developing personnel with expertise in pharmaceutical intellectual property.

At an unprecedented press conference at Kyoto University in April, Honjo said of Ono Pharmaceutical, "Their explanations at the time of signing the contract were not sufficient."

"If we don't have a fair partnership between industry and academia, Japanese researchers will have to take their 'seeds' abroad," he added.

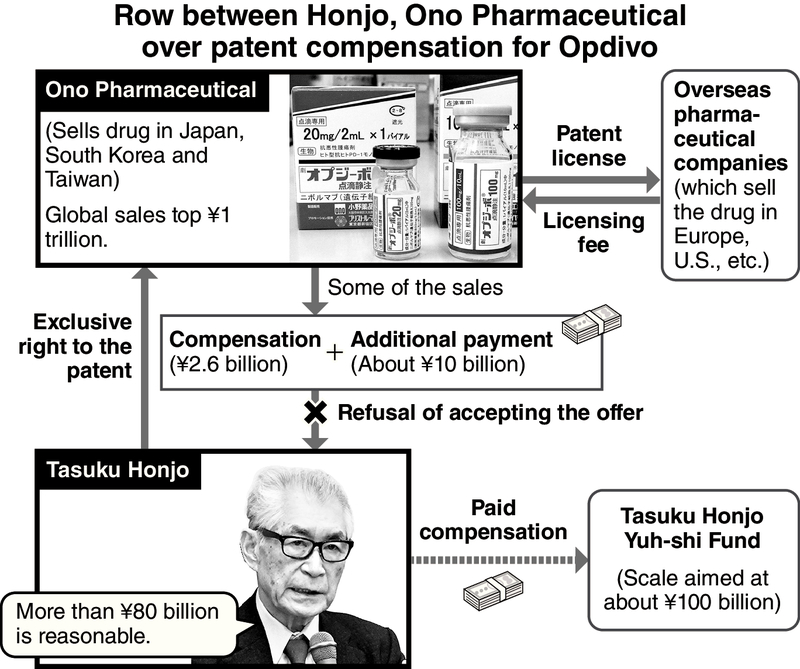

In 2003, with a view to developing a new drug that would make use of the PD-1 molecule found in the immune cells that attack cancer cells, Honjo filed a joint patent application with Ono Pharmaceutical. The resulting drug, Opdivo, which hit the market in 2014, is used for the treatment of skin, lung, stomach and other types of cancers. Opdivo's global sales topped 1 trillion yen by the end of 2018.

Meanwhile, the compensation offered by Ono for the use of the patent held by Honjo is about 2.6 billion yen. The Osaka-based company offered to pay an additional royalty, which is said to have been about 10 billion yen, but Honjo's side has argued that a fair figure should be more than 80 billion yen and has refused Ono Pharmaceutical's offer.

"At that time, cancer immunotherapy drugs were viewed as too good to be true, and all other companies refused to undertake [the development]. The terms of this contract are normal for a project with high development risks," Ono Pharmaceutical President Gyo Sagara said. The two sides have failed to reach an agreement in negotiations.

Researchers negotiate alone

Many intellectual property experts believe the contract that determined the compensation is valid and that the odds are against Honjo.

Among the factors culminating in an agreement that would appear unfavorable from Honjo's perspective is that during a time of inadequate intellectual property management at Kyoto University, Honjo personally negotiated and signed the contract despite his lack of experience with patents. At that time, universities usually took charge of intellectual property only when it was connected to research involving the use of a large amount of public funds. Otherwise, individual researchers generally applied for patents by themselves, relying on the help of companies.

Satoshi Omura, a Kitasato University distinguished professor emeritus who was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his contribution to the development of a drug for treating worm infections in the 1980s, also negotiated a royalty agreement on his own with the U.S. drug company with which he partnered for the research. Omura was initially offered to transfer his patent for 300 million yen. However, as this figure was insufficient to cover the research costs, he persistently pushed for compensation in alternative forms such as sales-based licensing fees. In the end, he was able to secure more than 20 billion yen.

Japan's national universities began establishing intellectual property management systems starting in 2004, when they were legally redefined as independent corporations. It was during that time that universities began applying for and retaining patents for promising results of research undertaken under their purview.

In the case of research by Kyoto University Prof. Shinya Yamanaka, who won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the development of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, Kyoto University applied for the patents for the cell manufacturing method among other things. The university has also worked to further upgrade its management of intellectual property by taking steps such as establishing an in-house startup to handle patent management and licensing negotiations.

Japan's technology licensing organizations (TLOs) act as intermediaries for contract negotiations between universities and companies under the Law on the Promotion of Technology Transfer from Universities to Private Business Operators. As of April, the number of TLOs stood at 35, and the number of patents handled by TLOs has risen rapidly.

More experts needed

However, given the costs associated with managing intellectual property, universities are not necessarily able to manage every possible patent. Even now, instances of individual researchers applying for patents jointly with companies are not rare.

In the realm of pharmaceuticals in particular, with the difficulty of predicting whether research will produce something that can be put into practical use, problems can easily arise if, after researchers negotiate by themselves, the resulting drugs generate huge profits. While it is possible to include a clause in a contract stipulating that royalties must be reviewed as development makes progress, many researchers are simply not well-versed in the intricacies of licensing deals. Some intellectual property experts have expressed the view that universities should follow up after their researchers sign contracts individually.

At present, however, there are few professionals at Japanese universities who have the ability to accurately ascertain the value of research projects. Many universities in the United States employ lawyers with scientific backgrounds and have robust systems that serve to provide guidance on patent strategies beginning at the research stage.

"Japan has many intellectual property experts specializing in machinery and electronics, but drug companies have few who are well-versed in pharmaceutical patents. A framework to cultivate such human resources needs to be developed," said Hiroshi Akimoto, a visiting professor at the University of Tokyo who has experience in taking charge of intellectual property for a major drug company.

Fund for young researchers

Honjo's refusal to give an inch in his quest for substantial royalties has been motivated by his intention to use the funds to support young researchers.

Last December, Kyoto University established the Tasuku Honjo Yuh-shi Fund, which uses profits from investments for research and personnel costs. Honjo has donated slightly over 50 million yen -- his entire award from the Nobel Prize -- to the fund. He plans to add to that his royalties from Ono Pharmaceutical, with the ultimate goal of scaling up the fund to 100 billion yen.

With the cuts to government subsidies, many Japanese universities are searching for solutions such as using similar funds to cover research costs. Among those managing large funds are Keio University with a 68.8 billion yen fund and the University of Tokyo with a 10.8 billion yen fund. Both figures are as of the end of March 2018.

However, outside Japan, institutions such as Harvard University operate funds worth trillions of yen and generate huge amounts of funding for research every year.

"A single advanced medical research project can require tens of millions of yen a year. The amount offered by Ono Pharmaceutical would in no way be enough to support many research projects over the long term," one university professor said.

A senior Kyoto University official also said, "With 100 billion yen, we would be able to offer steady employment to numerous researchers using the investment profits."

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, May 18, 2019)

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/