Ten years after coming to power, Australia’s sole remaining Liberal government is limping to what in normal circumstances might be the finishing line.

Since winning a third straight election in 2021, the Tasmanian Liberal party has lost a handful of MPs to retirement and rebellion, and faced criticism for failing to resolve a string of longstanding issues weighing on the state.

The former premier Peter Gutwein – easily the state’s dominant political figure of recent years, particularly during the Covid pandemic – left politics in 2022, citing exhaustion. His successor, the mild and moderate Jeremy Rockliff, has overseen a minority government since May, when two little-known backbench MPs, John Tucker and Lara Alexander, quit the Liberal party and moved to the crossbench.

The fallout has been ongoing, leading to Rockliff this week calling a state election for 23 March, more than a year before it was scheduled.

Tucker and Alexander, both conservatives, blamed their exit from the party on a lack of transparency over a controversial deal with the AFL to build a publicly funded stadium on the Hobart waterfront and the proposed Marinus electricity link across Bass Strait. But they were also unhappy about Rockliff’s stance on social issues – including his support for the federal Indigenous voice to parliament and a proposed ban on LGBTQ+ “conversion therapy” – and their personal career prospects.

They guaranteed the government confidence and supply, but voted with Labor and the Greens on motions and amendments. When Tucker started 2024 with a threat to bring the government down if it did not agree to new terms – and Rockliff responded by demanding the rogue MPs back all government legislation – the path to an early election was set.

The sense of a government struggling to manage itself has not been limited to the conflict with Tucker and Alexander. The attorney general, Elise Archer, left the cabinet and parliament in October after accusations of bullying behaviour (which she denied) and a public war of words with Rockliff.

In December the government recalled MPs from across the state for a special sitting to consider suspending a supreme court justice who faced criminal charges, only to discover during the day the vote would have been unconstitutional.

More consequently for Tasmanians’ lives, the state faces crises and failures in housing, healthcare, government transparency and environmental management. A commission of inquiry into the state’s response to child sexual abuse concluded with devastating findings but the government is yet to act on many of the recommendations Rockliff said he accepted, including closing the failed Ashley youth detention centre where dozens of workers abused children over decades. And Tasmania continues to have the worst year 12 school attainment rates among Australian states.

Despite this, the Liberal government goes into the campaign widely expected to win the most seats – though not necessarily enough to form a majority government.

Many of the problems facing the state are systemic, having existed when Labor was in power before 2014. Observers say the opposition has not spent the past three years providing a clear alternative. It has been dogged by factional infighting, problems in its administrative branch that forced a national executive takeover and a lack of clarity about what it stands for.

Richard Herr, a political analyst at the University of Tasmania, says on paper this election should be challenging for the Liberals. It is hard for any party to win a fourth term of government, the government comes to this election with significant baggage and barely won a parliamentary majority three years ago despite strong public support for Gutwein’s leadership during Covid-19.

But the government has at least one thing working in its favour. “The Labor party doesn’t appear to have rebuilt in opposition,” he says.

The headline division in the ALP has been over what to do about David O’Byrne, an MP from the party’s left who became leader immediately after the 2021 loss, but resigned two weeks later when he was accused of misconduct – unsolicited kissing and texting – by a former female colleague while he was a union official in 2007.

A report found O’Byrne had not breached party rules but the current leader, Rebecca White, said she would not work with him and the party decided in a split vote not to re-endorse him as a candidate. O’Byrne responded by announcing he would run as an independent.

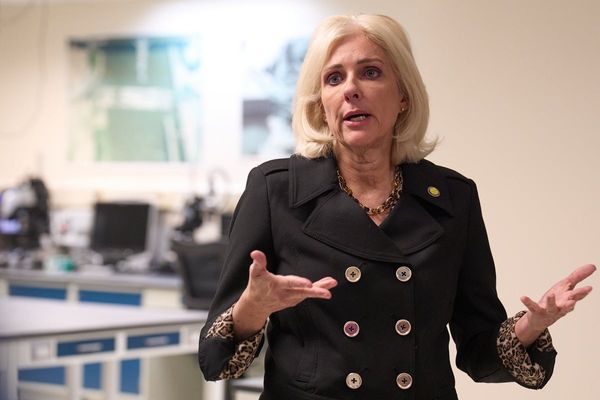

White is leading Labor to an election for a third time, having lost to Will Hodgman in 2018 and Gutwein in 2021. While Tasmanian election results can be difficult to predict, two recent polls found the ALP could again struggle to win 30% of the vote.

Most striking was an EMRS poll in November, which had Labor on 29%, well behind the Liberals on 39%. The Greens were on 12% and others – independents and possibly minor parties such as the Jacqui Lambie Network – 19%.

The Greens have long been a third party force in the Tasmanian parliament, shaping and, on one occasion, joining governments. But their support has been in decline.

At its peak in 2010, the minor party received nearly 22% of the vote and had an MP in each of the state’s five multi-seat electorates. Now it has only two, leader Rosalie Woodruff and the former Wilderness Society campaigner Vica Bayley. Both are based in Hobart. The party’s support outside its southern stronghold has slumped dramatically – by more than half – over the past decade.

It means none of the established parties go into the election campaign backed by a wave of public support or enthusiasm. Kate Crowley, an adjunct associate professor in politics at the University of Tasmania, says she cannot recall the electorate being so dissatisfied.

In her reckoning, the Liberals have performed poorly but Labor comes across as disingenuous and without an explanation of how it would address longstanding problems, and the Greens are seen to be “spinning their wheels”. Her conclusion: “I think independents are going to be the new kids on the block.”

Both the EMRS poll, and another by YouGov, lend support to this view. But it is unclear how this will play out under the Tasmanian electoral system.

Assessments of where things might land are complicated by the size of the Tasmanian parliament expanding at this election from 25 to 35 lower-house MPs. The change – which restores the parliament to its size before 1998 – was backed by all parties and followed complaints of MPs being overstretched and suffering burnout.

Under the state’s proportional Hare-Clark voting system, there will now be seven members elected in each of its five seats: Bass, Braddon, Clark, Franklin and Lyons. A candidate needs just 12.5% of the vote to guarantee their election.

It had been expected this change might lead to a wave of higher-profile candidates but so far there have been relatively few. The standout exception is Eric Abetz, the longtime conservative Liberal senator and party powerbroker who lost his federal seat after being pushed down the ticket in 2022. Though a divisive figure, he is considered a strong chance to win a seat in Franklin, covering Hobart’s south and east.

One of the big questions of the campaign will be whether the willingness to back independents and minor parties suggested in polls will translate into a significantly expanded crossbench, as it did at the last federal election.

As it stands the Tasmanian lower house has 11 Liberals, eight Labor MPs, two Greens and four independents. But three of those independents were elected as major party candidates, and will no longer have that backing.

The major parties have begun the campaign stressing they will not deal with the Greens to form government but leaving open the possibility of negotiating with others if necessary.

Most observers believe it will be, and it is likely the Liberals will be talking with crossbenchers in late March – as they have been for the past nine months.

Herr says there is a reasonable chance Tasmanians will elect more than five crossbenchers for the first time but cautions against assumptions that will mean a dramatic change in how the state is represented. “I’m predicting this is going to be a transitional election rather than a transformational one,” he says.