.jpeg?width=1200&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2)

In the summer of 1998, the filmmaker Darren Aronofsky could be found spray painting stencils of the pi symbol all over his native Manhattan – a bit of guerrilla marketing for his feature debut, π (or Pi). Meanwhile, on the other side of the country, little Austin Butler was a creative seven-year-old with an allergy to people. He’d play GoldenEye 007 on the Nintendo 64 when he wasn’t being shoehorned into after-school softball tournaments by his parents. “I’d come home crying,” Butler grins. “I didn’t want to be around other kids.”

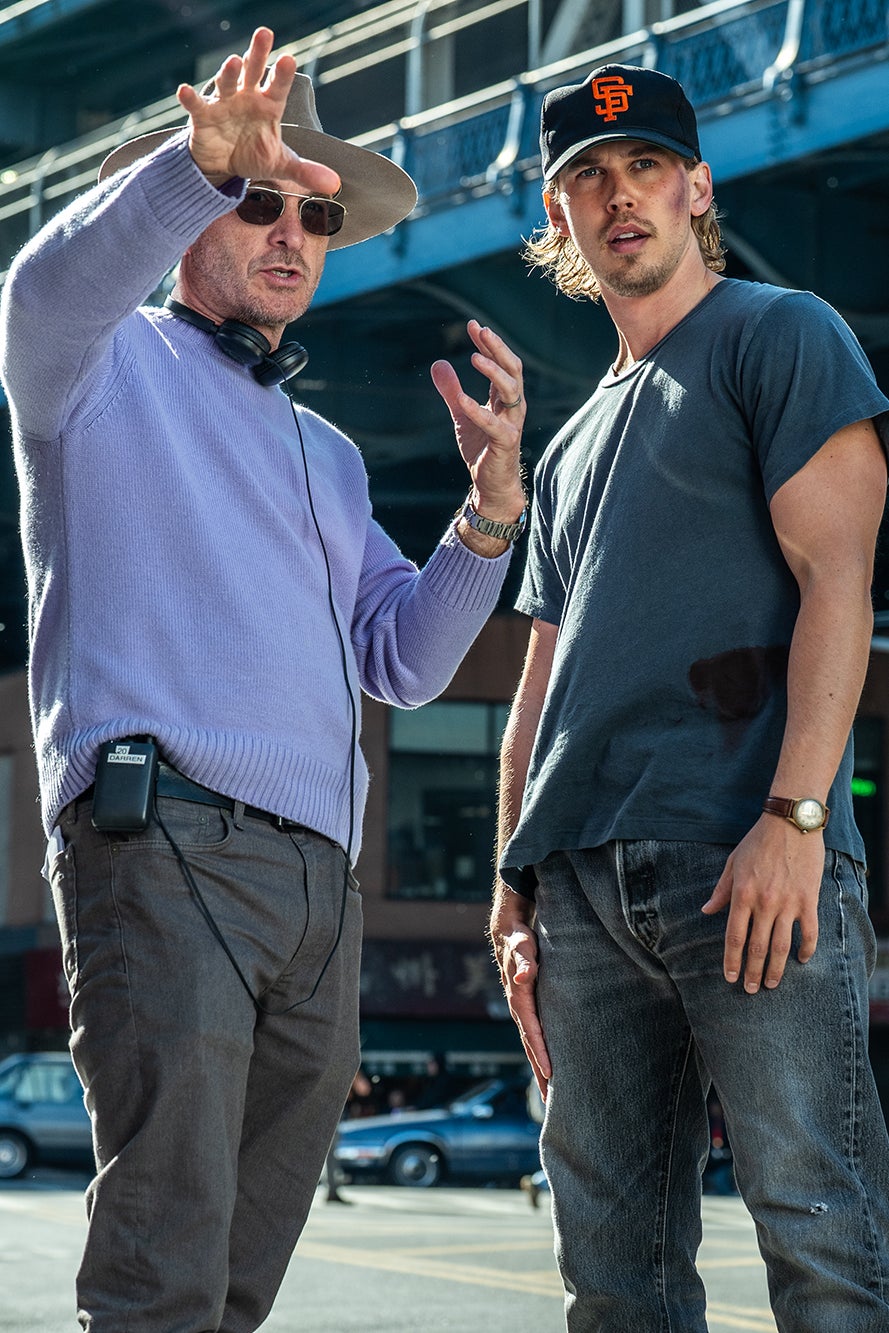

Today, the 34-year-old is one of Young Hollywood’s most in-demand actors, a pouty Brando disciple with an Oscar nomination for Elvis. Aronofsky, 56, is the man responsible for divisive shockers such as Mother!, The Whale and Black Swan; a director from the more-is-more school of cinematic button-pushing. The pair have collided for Caught Stealing, a brisk new thriller set in the summer of 1998 and, in many ways, inspired by that era’s filmmaking maxim: toss together some chugging action, real-world location shooting and a handful of beautiful stars and voila! Instant movie-dom.

We meet at the end of a day of press interviews that are decidedly different to those of the Nineties. “Have they got you eating Percy Pigs yet, Darren?” Butler asks. “Any Colin the Caterpillars?” Aronofsky, with the look of someone who’s just had needles stuck under his fingernails, winces. “They’ve had me doing some things,” he sighs. Aronofsky is, admittedly, a lot more bouncy and fun than you’d imagine for a man who transformed the 68-year-old Ellen Burstyn into a sallow, amphetamine-popping husk for Requiem for a Dream. But the games, props and zany taste tests of modern film junketing seem a bridge too far.

Caught Stealing is something of a pivot for both men. It’s a proper star vehicle for Butler after ensemble turns in Dune: Part Two and The Bikeriders, and a decidedly less oh-my-god-won’t-the-suffering-ever-cease job for Aronofsky. Butler is Hank, a one-time baseball pro who’s fallen on hard times. While taking care of his neighbour’s cat – Matt Smith has a lot of fun as said neighbour, a cockney layabout with a multicoloured mohawk – Hank is set upon by a pair of Russian goons, who themselves are tangled up with a pair of Hasidic gangsters. Zoë Kravitz is Hank’s panicked girlfriend, and Regina King, the tough cop attempting to make sense of it all. There is a blue key in Hank’s possession that unlocks something, a pounding score by British post-punks Idles, and rapper Bad Bunny as a slithering mafioso. Pursued by seemingly half of New York and with his loved ones targeted for death, Hank dives down a 24-hour rabbit hole of oddball violence.

Aronofsky has long had a tendency to grab hold of established actors and contort them into new shapes: Natalie Portman became a scary-skinny ballerina; Jennifer Lawrence a defiled goddess; Brendan Fraser a human blimp. With Butler, he wanted to make him a little more real.

Sometimes I say no to things that an early version of myself would have done anything for. And, emotionally, that’s very weird

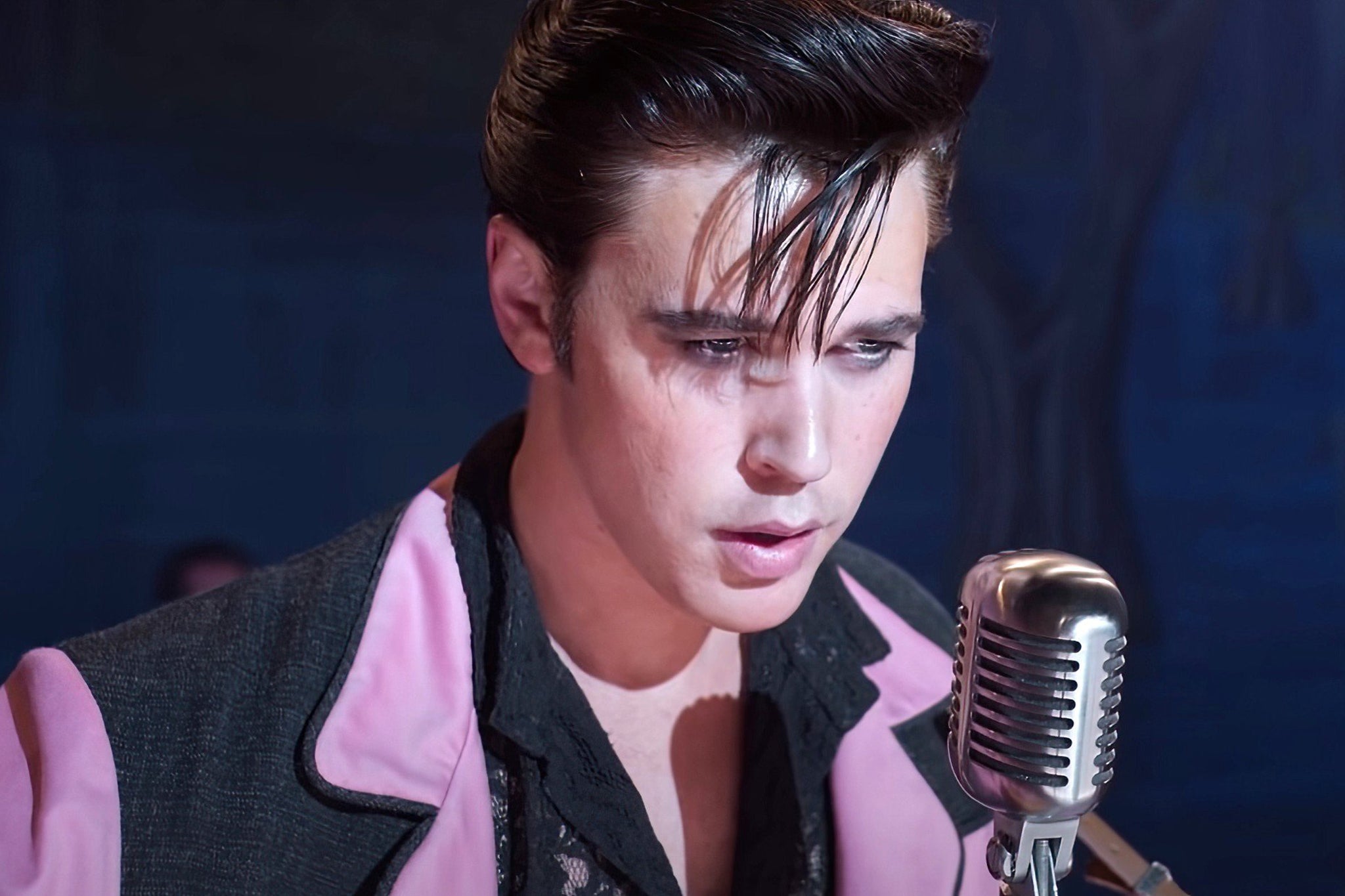

“I always thought there was unbelievable potential with this guy,” he explains. “What I like about this film is that, while Elvis and Dune were incredible performances, there was transformation going on.” He hesitates to call Elvis Presley a “character”, but the principle is true: Elvis was the most superhuman a human being could ever really be. The bald, sociopathic Feyd-Rautha in Dune was, to put it lightly, a space loon. “Here Austin’s a bartender in the East Village, you know? And it forced him to play all these different colours.”

Butler – tall, tan and handsome in a way that’s frankly greedy – agrees. “That was at the core of why I wanted to do it,” he nods. “It felt more raw and vulnerable – like I didn’t have this other skin.” Plus he’s always loved Aronofsky. He was acting in a student film at the age of 12 – while still living at home in Anaheim, California – when its director recommended he watch Requiem for a Dream, Aronofsky’s nightmarish depiction of drug hell. “Oops,” Aronofsky jokes. Butler smiles. “Yeah, I couldn’t sleep for weeks. But I also fell in love with how visceral his work is. When I was in my twenties I invited a bunch of friends over and projected The Fountain in my backyard, you know?” He’s referring to Aronofsky’s 2006 treacly multiverse romance with Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz; it’s a film that about 12 people have seen, so Butler’s fandom goes hard.

Despite being steeped in cinema from an early age, Butler says it took him a while to find himself as an actor. He was, believe it or not, a bit of a child star – or at least someone constantly in the orbit of every major teen icon of the Noughties, from Miley Cyrus (he appeared in two episodes of Hannah Montana) to Selena Gomez (one episode of Wizards of Waverly Place) to the Jonas Brothers (two episodes of their eponymous sitcom, Jonas). His breakthrough, of sorts, arrived in the form of 2013’s The Carrie Diaries, a short-lived (and often entirely forgotten) Sex and the City prequel aimed at teens.

“I’m very grateful for that show because it allowed me to move to New York and see theatre for the first time,” he remembers. “When I had days off, I’d just go to see plays. Theatre wasn’t a part of my life in LA, where you’re also very isolated from humanity. You’re in your car, you’re on set, and then you’re in your car again and then you’re at home. In New York I’d ride the subway and go to museums and see live music – it made me more curious. It was like a shot of life into my heart.”

The Carrie Diaries was cancelled after two seasons, allowing Butler to actually appear in plays himself, first in a Los Angeles production of Steven Drukman’s Death of the Author and then, on Broadway, alongside Denzel Washington in a 2018 revival of The Iceman Cometh. The critic Hilton Als, writing in The New Yorker at the time, was an early fan. “Although there are many performers in [this play] ... there is only one actor, and his name is Austin Butler,” he wrote. “Tall, with fair hair and light-coloured eyes, he conveys, through economy of movement and facial expression, what many of his castmates try to show by shouting and grandstanding: his character’s inner life.”

Further work followed, notably as a Charles Manson devotee – alongside other future megastars including Margaret Qualley, Sydney Sweeney and Oscar winner Mikey Madison – in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood. It was Denzel Washington who then hopped on the phone to recommend Butler to director Baz Luhrmann, who was busy trying to find his Elvis. In the end, Butler won that role over reported rivals such as West Side Story’s Ansel Elgort (imagine!) and Harry Styles (the equivalent of staring into the mouth of hell, surely?). The part shot him into the Hollywood stratosphere, earned him a Golden Globe and a nomination at the Oscars, and gave him an Elvis drawl that stuck around long after filming had completed but seems to have subsided by this point.

I ask Butler if he’s heard of “iPhone face”, an internet-created term for young actors who don’t convince in period pieces – potentially due to their tweakments or plastic surgery, or their gleaming white, very 21st-century veneers. There’s also, more generally, the underlying sense that they absolutely know what the Call Her Daddy podcast is. “I have not heard of iPhone face,” Butler says. Which is strange, I hedge, because Butler has a kind of anti-iPhone face. Of his recent run of films, only this week’s Eddington – in which he cameos as a conspiracy theorist exploiting the 2020 Covid panic – is at all contemporary. “Is that bad?” Butler asks anxiously. “No, it’s good!” Aronofsky says. “You live in all the time zones, except for where there’s an iPhone.”

Butler takes a quick verbal inventory of his films. “I actually can’t remember the last modern thing I’ve done,” he says. “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood, The Bikeriders, Elvis, this, [the Second World War limited series] Masters of the Air … Maybe my face is so imperfect that it doesn’t look right for modern times, I don’t know.”

That’s not exactly my theory. Unintentionally or not, Butler’s professional choices feel strategic and thoughtful – led by great directors and, usually, original ideas – which in turn feels like a throwback to a more traditional and classic kind of movie star. Then there’s his easy, confident masculinity on-screen – he’s a real dude, a little brooding and intense, but with an undeniable fragility to him. It makes him feel oddly timeless, and therefore perfect for parts outside of the here and now.

Aronofsky says that he remembers taking a few acting classes in the Nineties, purely because he knew it would be useful to him as a filmmaker. “This one teacher said that, once you make it, the hardest thing is picking what you do afterwards,” he says. “And Austin’s a really good picker. I’ve talked to him about it, and seen how he does it. He’s doing it the right way. He’s thinking hard.”

Butler agrees it’s difficult. “Sometimes it means saying no to things that an early version of myself would have done anything for,” he says. “And, emotionally, that’s very weird. I still feel like that 12-year-old kid who was just auditioning for anything, you know?”

“But I look at what Leo’s done in his career,” he adds, referencing DiCaprio, the highly selective star who’s regularly cited as an inspiration by everyone from Timothee Chalamet to Jacob Elordi. “The specificity and the intention of every film [he makes], and also being able to create the space around each film so that you can really dedicate yourself to it and not just work back-to-back. I remember talking to De Niro about this – which is crazy, like even saying that.”

“Don’t you mean ‘Bobby’?” Aronofsky jokes. “You talk to Al lately? Meryl?”

Butler blushes. Honestly, just give it time.

‘Caught Stealing’ is in cinemas from 29 August

Austin Butler thought he was ‘dying’ after going temporarily blind before Bikeriders

The Joaquin Phoenix-starrer Eddington brilliantly skewers modern America – review

Mila Kunis admitted her diet for Black Swan required ‘little eating’

Rhona Mitra on healing, horses and leaving Hollywood behind: ‘I had to save my soul’

Giving up movie stardom was Tom Hiddleston’s smartest career move