Billed, inevitably and disgracefully, in some extremist quarters as a battle between the rights of “illegals” and the wishes of the people of Epping, the Court of Appeal was nonetheless perfectly right to quash the judgment of a lower court in the Bell Hotel case.

The latest decision – understandably, given the distressing circumstances of a recent serious crime – is a disappointment to Epping Forest District Council and the residents of the market town, by no means all agitators. However, it was nothing to do with human rights or the European Convention, and much more about planning and British immigration law.

The High Court was right to weigh in the balance the chaos and confusion that would follow nationally if the Bell Hotel – and quite possibly every other one used in this way – were to be emptied of all their tens of thousands of residents in a matter of weeks. That was a legitimate legal argument, and a wise one in practical terms.

Equally sound was the judge’s observation that to do otherwise would incentivise people to protest, so as to force any local council and a court into giving in, on a planning issue, to the demonstrators’ demands. If carried to a conclusion, such a situation would lead to mob rule.

The problem, however, has not been wished away by the judge’s words. In due course, another court may rule that hotels cannot be used for housing people, and require proper planning. In which case, the government’s dilemma will return.

“Asylum hotels” evidently upset some people, if only because they can be highly visible and there are so many myths about them. Thus, the judgment still leaves approximately 32,000 people in hotel accommodation, which is plainly not politically or financially sustainable. The image of asylum seekers revelling in “luxury” is false; by the time these places have been converted for their new “guests”, conditions are rather more cramped and basic.

This was always a problematic way to deal with the increasing numbers of people who were being kept in legal limbo by the previous administration – and that did undoubtedly force the last government and this one to persist with effectively commandeering hotels in local communities.

Because successive Conservative home secretaries placed such store in the Rwanda plan, and made claiming asylum illegal for people arriving irregularly, no claims were processed – it would have literally been a crime for officials to do so. But nor were the would-be refugees sent back to their home countries, or anywhere else.

Even had the Rwanda scheme been up and running at full capacity, it was always too small to cope with more than a few thousand applicants a year. The argument ran that it could be expanded, which would necessarily take time, and that it would serve as a deterrent. Yet there was little sign of that at the time, and a determined immigrant, whether refugee or economic migrant, would simply evade detection by the authorities and not bother with trying to claim a right to remain.

As well as being deeply unsuitable, both for the asylum seekers and the communities who suddenly find themselves with their local hotel converted, the use of hotels is expensive, even allowing for the greater concentration of residents. Under Labour, the Home Office has managed to cut the room rate per night from £162 to £119, but the total cost of asylum accommodation contracts, initially estimated at £4.5bn, is now estimated to be £15.3bn over 10 years, according to the National Audit Office. These are substantial sums by any standards.

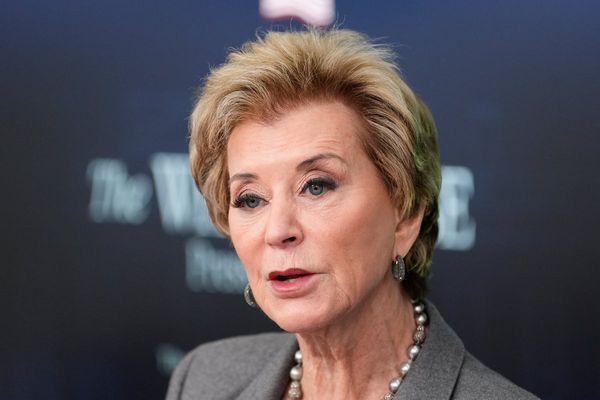

Ms Cooper wants to phase out “asylum hotels” by the end of the parliament. It may be that that is the only practical and realistic timetable, and the pace may be forced by a future court ruling. More pressing, though, is the weight of public opinion. So she will surely have to look again at the situation in these hotels, regardless of future legal developments.

Other comparable countries do not use hotels to anything like the extent that the British do, and have proved far more adept at building large-scale, basic, clean, safe accommodation away from town centres and communities, and where a greater degree of supervision, if not detention, is possible. There would be a cost involved, and it is difficult to see what might be the end use for such a facility, if and when the current phase of the crisis is over – but those are arguments that she will have to put to parliament if she wants to respond to the acute concerns of the public.

Ms Cooper is certainly right to concentrate on speeding up the process of assessing claims, and streamlining the procedures such that spurious legal actions are avoided. She might also usefully review why, in some cases, asylum claims have a far higher rate of success in the UK than other European countries. It is not immediately clear whether this is a reflection of different patterns of migration to the UK (ie countries of origin), or in the criteria British officials apply as compared to our continental neighbours.

All that said, even when the asylum backlog is cleared and the numbers of failed asylum seekers being returned begins to accelerate, there remain some fundamental questions that need to be faced up to by lawmakers and public alike.

The most basic of all centres on numbers. If the world is so volatile and conflict so widespread, as is becoming the case, can a theoretically uncapped commitment to perfectly genuine refugees plainly fleeing for their lives be sustained? If it can, or if it should, then how can this be done on a basis that carries public support? If not, then does the current formulation of the European Convention on Human Rights, and the way judges interpret it, need to be reformed to reflect a changing mood in democratic societies?

The immediate problems of appropriately housing sometimes desperate people who’ve lived through unimaginable horrors and settling their status are obviously urgent enough to preoccupy ministers, but that is no reason to avoid some uncomfortable dilemmas. The case for universal human rights should be overwhelming and compelling, but it cannot be taken for granted.

Getting rid of the ECHR won’t stop a single boat of migrants

How quickly would Farage’s migrant plan unravel? Just look at Greece…

Think Rylan is right about asylum-seekers? So does Tommy Robinson…

The government must consider all options for a more forceful approach to migration

Tell us what Labour actually stands for, prime minister

Nigel Farage’s ‘fag packet’ asylum plans are a golden opportunity for Labour