On September 12, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended the next round of COVID shots for everyone 6 months and older.

The CDC indicated that the shots would be available within days in pharmacies and doctor's offices across the country.

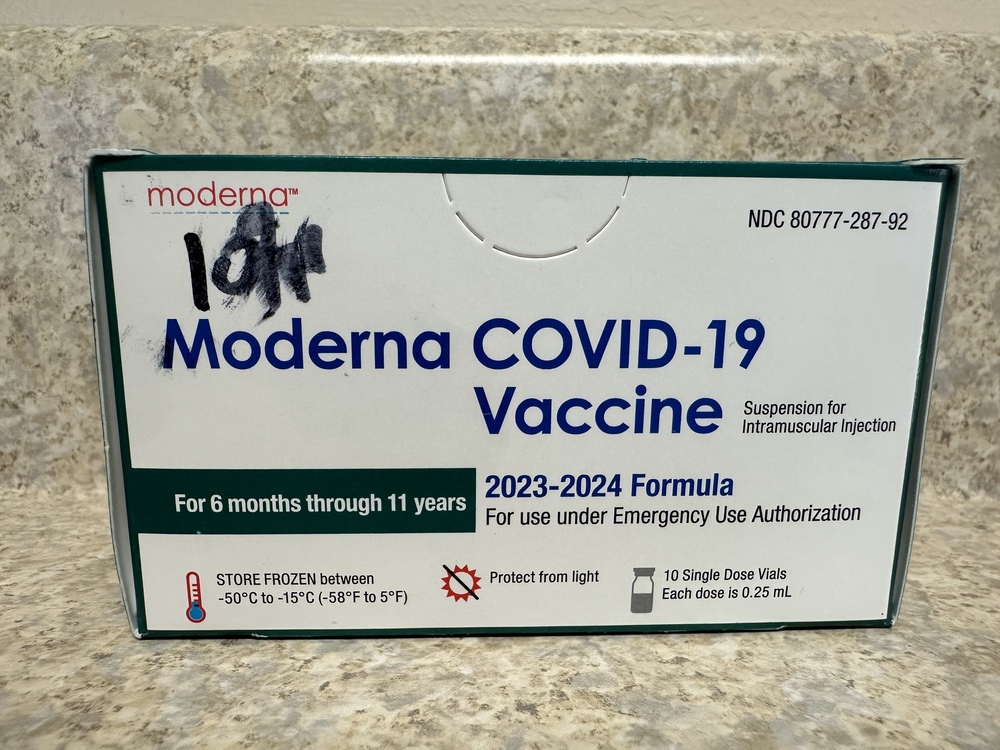

But more than a month later, some parents report ongoing difficulties in finding the pediatric versions of the new COVID shots, for children 6 months to 11 years old.

A confluence of problems – from technical rules about who can administer shots to small kids, to the lack of accurate information online on where the kid-sized doses can be found – is making it hard for some parents to get their kids protected.

"Nobody has accurate information on where doses actually exist. It's just an absolute logistical mess trying to find information and it was driving me insane," says Anne Hamilton, a Los Angeles resident, who searched for weeks to find a pediatric dose for her four-year-old son, Jimmy.

Hamilton checked first with her son's health system. The website was only offering vaccine appointments for adults.

"The popup [on the website] says 'new vaccines are expected in late September, try again later.' Well that's a frustrating message to read when it's October, and they're not giving you any other information," she says.

One problem that has caused headaches for parents has been trying to find doses covered by their insurance.

For the first time since the start of the pandemic, this COVID shot isn't being paid for by the federal government. Now, pharmacies and doctors have to purchase the vaccines from suppliers and stock them onsite. And families need to use their health insurance to pay for them — and that can be complicated.

After days searching online and many false leads, Hamilton finally found a pharmacy over an hour away in Palmdale with pediatric doses. She called to make sure they actually had the shots, and also accepted MediCal, her son's government insurance.

After being assured of both, the Hamiltons made the hour-long drive. But when they arrived, the pharmacists said that couldn't give Jimmy the shot, because he was under 18 years old. Hamilton called MediCal to clarify.

"The MediCal phone representative explained to us that they need to go through the Vaccine For Children Program," she says. "So we're like, alright, we don't know what this program is."

As a pediatric MediCal recipient, Hamilton's son could only get a shot from a participating provider with the federal government's Vaccines For Children program.

"Nobody put out the information that children on MediCal needed to be vaccinated through the Vaccines for Children program," Hamilton says.

"Nobody has information on how to find a pop-up [clinic] near you because half of those aren't even listed on the MyTurn.gov page," she says, referring to a vaccine appointment website run by the state of California.

Hamilton was directed to a different California-run website that was supposed to show the location of Vaccines For Children providers across the state.

"The website just flat out doesn't work," Hamilton said after checking it.

Frustrated, she emailed the California Department of Public Health, which told her they were aware the website was down and that "IT was working on it." No one from CDPH offered to help Hamilton or direct her to the provider list she needed, she claims.

After a reporter with LAist and KPCC asked CDPH why the Vaccine for Children's Google-enabled map was not working, the website was fixed. However, it only shows participating providers, while neglecting to indicate if those doctors and pharmacies have pediatric COVID vaccine in stock. Parents either have to call each provider individually to see if they are taking patients and have the shot, or try to cross reference with the federal vaccines.gov website.

Hamilton was left frustrated and in tears.

"I know parents all over the country who are looking for doses. It's a hunt for everyone right now," she says.

Different vaccine supplies for different insurance

There are two parallel vaccine systems in the U.S., and which one children use depends on their insurance. Children with commercial health insurance get vaccines through the commercial market. But kids with government insurance such as MediCal get shots through the federally funded Vaccines for Children program — and only participating providers, like Orange County pediatrician Eric Ball, can give them the shot.

Under the Vaccines For Children program, "we actually place an order, the vaccines come to us, the government has paid for them already, and then we distribute them to patients who have those insurances, for free," Ball explains.

For children covered by commercial insurance plans, health care providers need to purchase the amount they think they'll need ahead of time. But Ball says many pediatricians aren't stocking or administering the COVID shot for those children, because they can't afford to.

"A lot of pediatric practices are small businesses and this means we have to expend a lot of money up front to be able to buy these vaccines and then wait weeks or months to get that recouped," he says.

If parents seek shots at a pharmacy, they may confront another obstacle: regulations that restrict the types of providers who can administer vaccines to children. Pharmacists can only vaccinate children 3 years and older under a temporary federal law. That leaves out young children between 6 months and 3 years old, who have to see a medical doctor.

"We have a very long list in our office of families who are waiting for the day that our COVID vaccines come in so we can finally start vaccinating them. There's been a lot of frustration," Ball says.

Ball's office participates in both pediatric vaccine systems. Through Vaccines for Children, his practice did receive some pediatric doses, but he can only administer them to qualifying patients.

For his commercially-insured patients, it took over a month to get a delivery of just 100 pediatric COVID doses. It's not nearly enough to meet the demand.

"It's a shame because we've had so many missed opportunities since this vaccine was approved over a month ago," he says.

"We've had lots of patients who come in who want to get their kids vaccinated, especially young children and babies who don't have the protection of previous vaccines."

Thousands of doses ordered, hundreds arrive

St. John's Community Health is a federally-funded safety-net clinic with multiple sites across Los Angeles County. The network serves low-income children and families, and for its pediatric vaccines the clinic is totally dependent on the Vaccines for Children program. But president Jim Mangia says that for the new COVID pediatric vaccine, their orders are being cut.

"We ordered 3,000 (pediatric doses) last week, we got 500," he says.

But St. John's provides care for 50,000 children, Mangia says. Because of the shortfall, St. John's isn't advertising the COVID vaccine or doing email or text blasts to spread the word, as the staff typically might.

"We're basically holding back," he says. "If someone asks for it we're providing the vaccine, but we're not doing the level of outreach that we normally do to get people vaccinated because we don't have enough supply yet."

The Vaccines for Children program is run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. On a recent visit to Los Angeles, CDC Director Mandy Cohen said she's not aware of any COVID vaccine supply or ordering issues.

"There's no ordering caps, we're hearing that folks are getting shipments within three or four weeks," she said. "I will say personally my kid's pediatrician has vaccine and has had a COVID vaccine clinic, so the vaccine is out there."

Anne Hamilton's son Jimmy finally got the shot through a pop-up clinic run L.A. County. She feels lucky to have found it.

"I told one of my friends that I was going to get my kids their shots and she said 'You found pediatric vaccine? I can't believe it.'"

A critical need as winter approaches

Pediatrician Eric Ball is concerned about what the slow rollout will mean for vulnerable babies and toddlers, who are too young to have been vaccinated before and need multiple shots before the predicted winter COVID surge.

"If we want to get these children vaccinated for gatherings such as Thanksgiving and the winter holidays, it's critical that we start doing this now because this is not a one-and-done kind of situation. We need these babies to get multiple doses over multiple weeks before they can be adequately protected," he says.

Meanwhile, children continue to get infected. One of Ball's 4-year-old patients tested positive on the same day his medical office finally received 100 doses of the pediatric vaccine. The boy's mother had tried to get him vaccinated earlier, but couldn't find a provider with the shots.

"As a pediatrician the only thing that hurts me worse than seeing a child get sick or hospitalized is them getting sick or hospitalized by something that I could have prevented. And if I don't have the tools to prevent that, it hurts me and it's very sad," Ball says.

This story comes from NPR's health reporting partnership with LAist and KFF Health News.