.png?width=1200&auto=webp&trim=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

The small city of Scottsboro in Northeastern Alabama is home to a store selling unclaimed luggage, a pretty park filled with geese, and a classic American diner serving some of the best grilled cheeses and soda floats in the South.

It was also the location of one of the most significant events in civil rights history – an event that directly impacted the Movement of the 1950s and 60s and had ramifications that are still felt in the United States today.

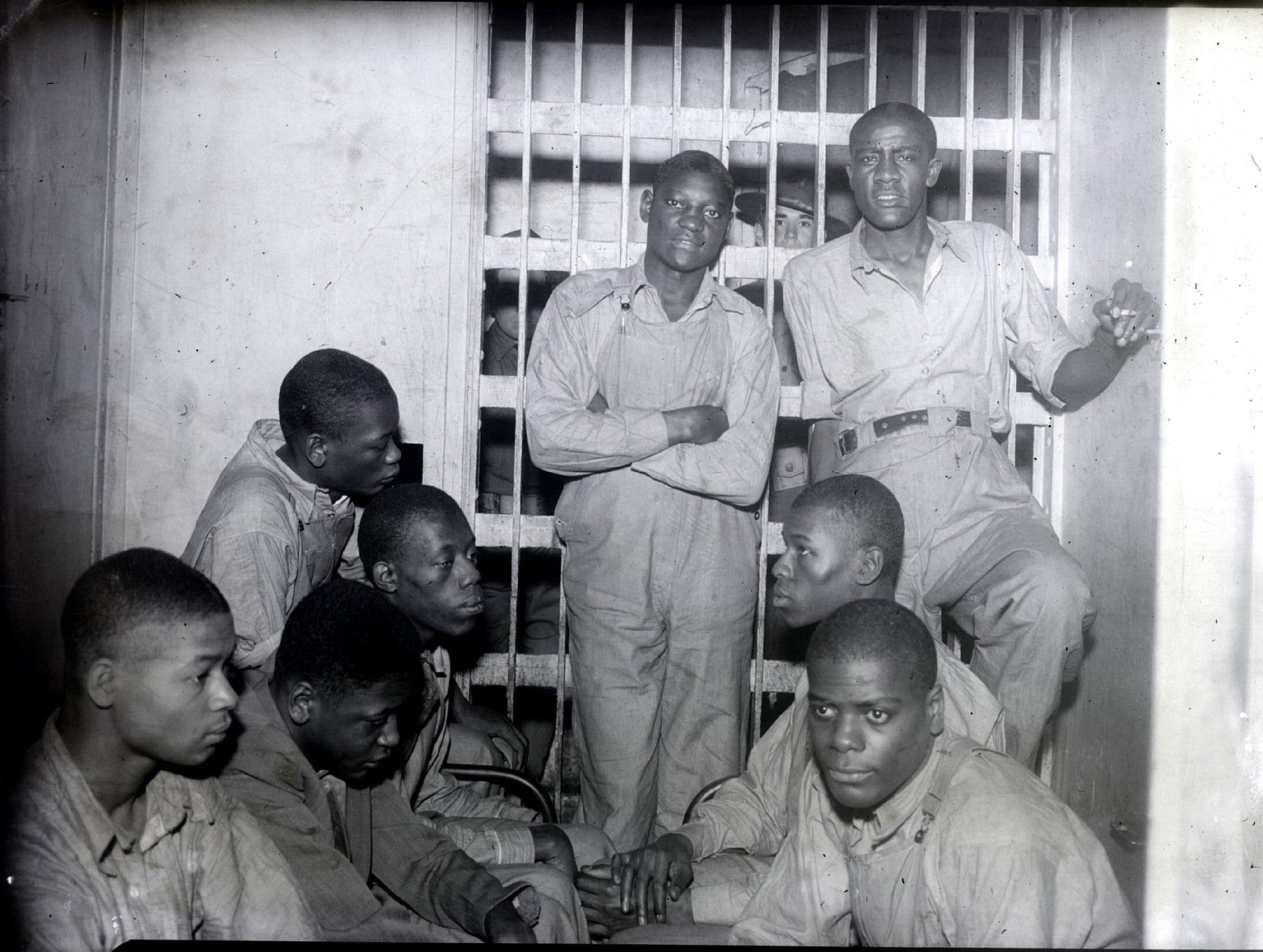

In 1931, nine African American young men and boys were travelling on a Southern Railroad freight train when they became involved in an altercation with a group of white men who were then thrown off the train. When the train pulled into the town of Paint Rock, the Black men were arrested for assault and taken to Scottsboro, Jackson County, where they were jailed.

.jpeg)

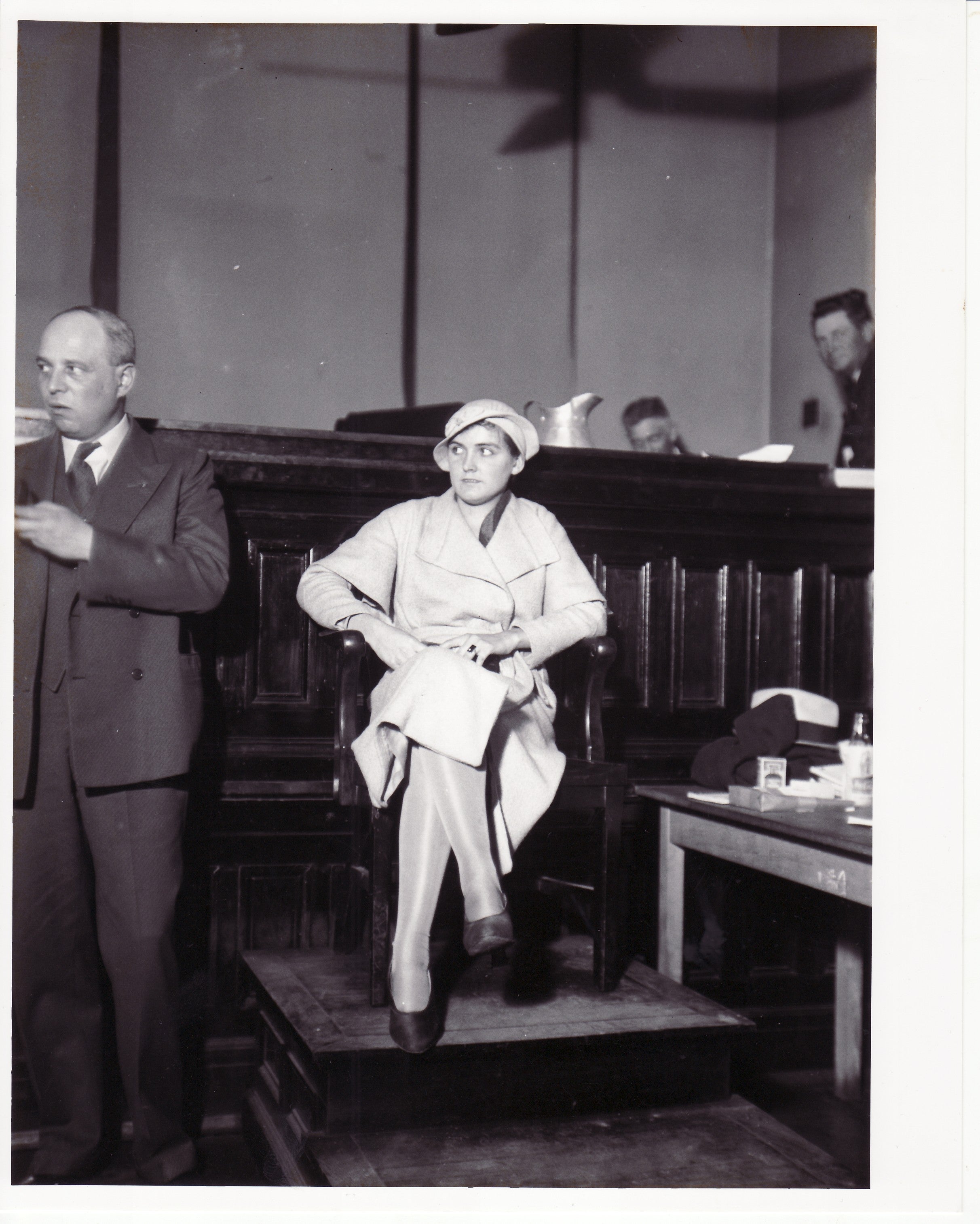

The situation escalated when Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two white women from Huntsville who were riding the same train and were facing charges of vagrancy and illegal sexual activity, falsely accused the nine African American men and boys of rape.

That night a mob gathered at the steps of the jailhouse in Scottsboro baying for blood and threatening to lynch the men. It was only after Sheriff Matt Wann stood in front of the crowd and insisted he would kill the first person to come through the door that they backed off.

The “Scottsboro Boys”, the youngest of whom was just 13, were tried by the State of Alabama in a series of four trials at the Jackson County Courthouse between April 6 and April 9, resulting in nine convictions and eight death sentences – for a crime that never happened.

This was a time when Jim Crow laws were deeply entrenched in the South; when African Americans were relegated to the status of second class citizens, and segregation was both legally and socially enforced. Jackson County was severely impoverished, and many Black residents had moved to the more industrialised cities to seek employment, while those who stayed faced discrimination and disenfranchisement.

Following the trial, protests erupted in the north of the United States, and in 1932 the Supreme Court overturned the convictions based on the fact that the men had not received adequate legal representation. Over the following seven years, the State of Alabama repeatedly retried and convicted the nine Scottsboro Boys with the Supreme Court once again overturning the convictions. In total, the men and teens spent 102 combined years in prison (one man was behind bars for nearly 20 years), despite being completely innocent.

The first trial occurred more than two decades before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus leading to the famous Bus Boycott. It would be another 30 years before Dr Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington in 1963, with President Lyndon Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act into law the following year.

Yet these events in the 1930s paved the way for a Civil Rights Movement that changed America – and the world.

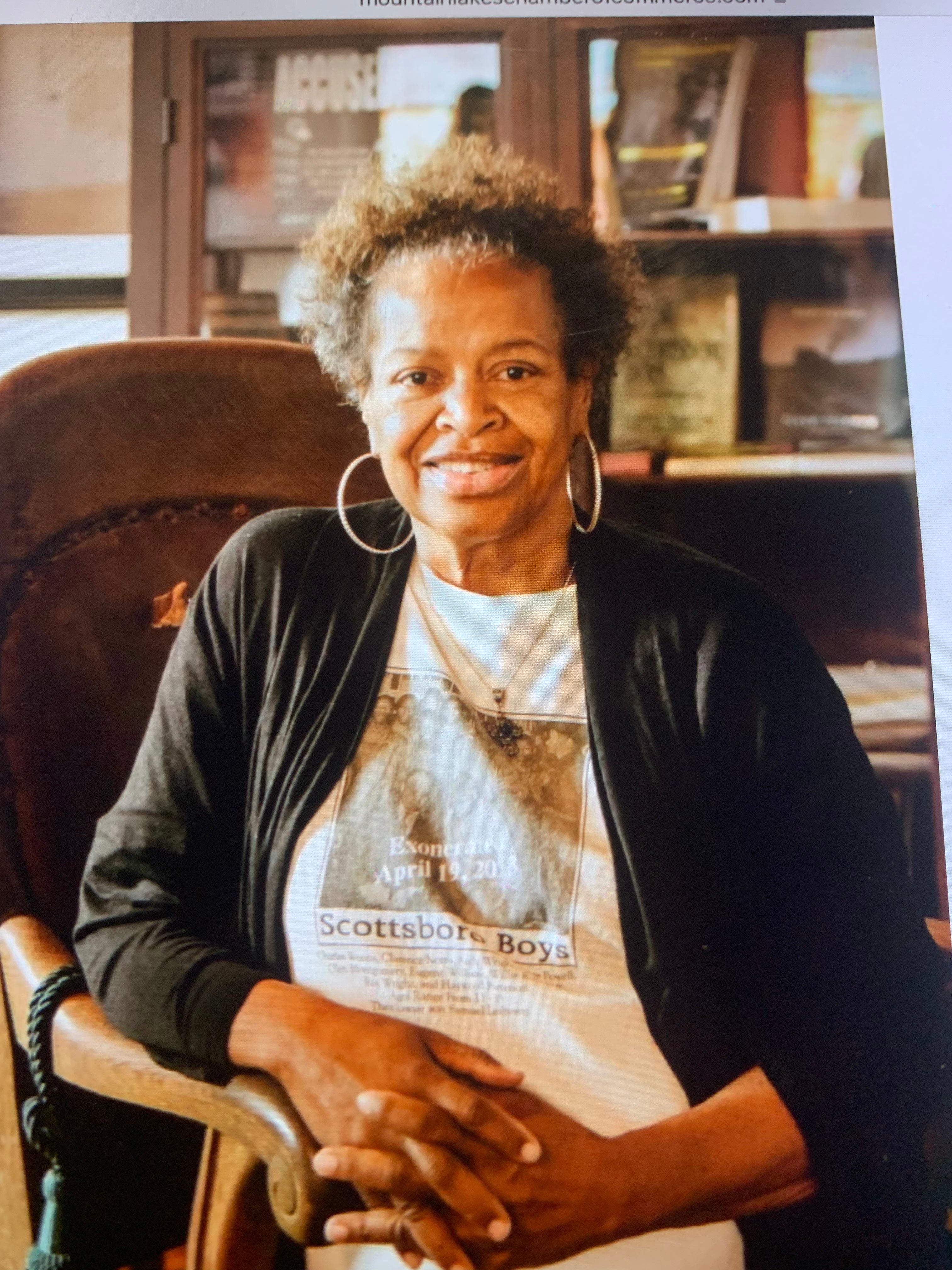

In an unassuming white brick church just out of the town centre stands the Scottsboro Boys Museum. It was founded in 2010 by local activist Shelia Washington after she uncovered the story of the nine teenagers and became determined that this miscarriage of justice would never be forgotten.

But Sheila found herself grappling with a community that would, if fact, rather this dark episode of their history was forgotten. Historian Thomas Reidy, who now serves as executive director of the museum, explains to The Independent that the city feared that it would look bad by being known for a case that exposed the ugly core of racial discrimination in the American South.

Thomas, who hails from New York state but now lives in Huntsville, Alabama, adds: “People who grew up in the 70s, 80s, 90s, they weren’t taught this story. Sheila wanted to correct that.”

In the face of death threats, hostility from the community and no money – one councilman vowed that the museum would “never see a penny” of funding from the city – Sheila forged onwards, determined that the Scottsboro Boys' story be told.

Thomas said: “It would have been easy for her to quit. But it became her reason for being, her passion. She had this stubbornness and single mindedness. She persisted.”

Sheila dreamed not only of opening the museum, but also of having the men pardoned – of the nine, only one had received a pardon from the State of Alabama before he died. But there was a serious barrier: in 2010, the State did not pardon dead people.

Sheila refused to accept this and set about calling congresspeople in order to change the law. This was an almost impossible feat for one person to achieve, yet less than a year after Sheila was told a firm “no” by the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles, the governor Robert Bentley signed the Scottsboro Boys Act into law. In 2013, the nine Scottsboro Boys – Haywood Patterson, Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Eugene Williams, Charley Weems and Roy Wright – received posthumous pardons.

The Scottsboro Boys Museum now strives to work with educational facilities to ensure that civil rights stories like this one are not erased from history.

Thomas explained that most people think of the Civil Rights Movement as starting with Rosa Parks or Emmett Till (the 14-year-old African American boy who was abducted and lynched in Mississippi in 1955), but many historians consider it began with the passing of the 14th amendment.

He says: “You can’t draw a true line from 14th amendment to Martin Luther King without going through Scottsboro. It's as central to the story of civil rights as any other moment.”

School groups have visited from across the States – from South Carolina to Chicago – but such was the resistance from the community that it wasn’t until 2023, a full 13 years after the museum opened, that the first schoolchildren from Scottsboro itself visited.

While the Scottsboro Boys story shows some of the ugliest parts of humanity, Thomas points out that it is also filled with heroes – from the sheriff who stood on the jailhouse steps and refused to let the mob in, to the New York lawyer who fought the Scottsboro Boys case, and the many African Americans who quietly persisted at a grassroots level to stand up against racial discrimination. This is something he tries to convey to the schoolchildren who visit. He said: ”We talk about what it takes to stand above the crowd.”

Sheila died in 2021, but the team at the museum have continued with her goal to make Scottsboro known, not for racial hatred, but for reconciliation, healing, and promoting civil rights.

This is a theme that is emerging in the state of Alabama, with tourism starting to focus on key locations of the Civil Rights Movement. Visitors are now encouraged to visit places such as Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, site of the brutal Bloody Sunday beatings of civil rights marchers; the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham that was bombed in 1963, resulting in the deaths of four young African American girls; and the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church where mass meetings were held to organise the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Thomas believes this is particularly important when we consider the issues of censorship that are afflicting the United States right now.

He adds: “When schools are forced to pull books off library shelves, museums like this are more important than ever.”

Where to eat, drink and stay in Anchorage, Alaska

10 Labor Day destinations for a last-minute break

From smashburgers to mafia pasta: why Britain can’t quit American dining

I lived in New York for seven years – this is the best hotel in the city

How New York’s immigrant communities built a culinary capital

This chilled-out beach town is the underrated Miami alternative you should consider