When astronauts describe looking down on earth from space, they sound like the ultimate hippies. Gazing down on their fragile yet beautiful home they generally experience an eco-epiphany, fully appreciating how we are all children of the Earth. Fair enough. It must be quite a trip.

But what’s the plan for ensuring a sustainable space when mars-one.com aims to send a crewed mission to the Red Planet by 2026 while, elsewhere, there are plans to mine some of the 12,000 space rocks orbiting earth? There are big questions to answer. Who makes sure that this happens ethically and equitably, in a way that doesn’t trash space for future exploration? I’m taken with the New Scientist’s idea of a Martian Magna Carta.

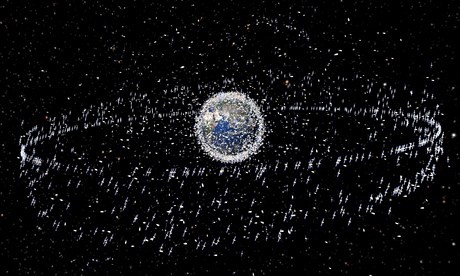

There should be another one for satellites, already the source of a major problem. Since Sputnik launched in 1957, thousands of satellites now orbit the earth. Some, often government ones, operate in the lower earth orbit (LEO), but many others, usually commercial, are geostationary (GEO) for telecommunications, broadcasting and weather. There is a catch, however. As space scientists put it: what happens in GEO stays in GEO.

The hostile environment limits the lifespan of satellites to an average of 15 years. At the end of their life, unless they can be propelled to a higher orbit where they will disintegrate more quickly, they become persistent space junk. A commercial organisation could, by the way, choose to ignore this UN protocol on orbital debris, and use the final fuel boost to eke a little more longevity out of the satellite instead.

There are also now an estimated 500,000 chunks of manmade space junk in orbit. In the film Gravity, Sandra Bullock and George Clooney’s attempts to fix the Hubble telescope are thwarted by this issue – and it is a real threat. In 2009, two satellites collided: one, defunct and Russian, hit another, commercial and American. Both were “destroyed” and resulted in 1,400 new pieces of junk in orbit. Last year the International Space Station had to reposition several times to avoid space junk.

Space exploration has left a mess that might make it too dangerous for future generations to explore and we’re running out of time to solve it. The organisations that cause the mess are charged with solving the problem and policing it. So the solutions are being deferred to future generations, as with that Earthbound problem, climate change.

Green crush

Wilmur is an old lady now and is looking for a new home. Until she finds the perfect pad, she’ll be relaxing on cushion-strewn sofas in a Shrewsbury cottage and following a sedate but loving routine. This is Oakfield Old Dogs Home, a residential lodging for elderly canines. The cottage has recently been converted for senior dogs who would find life in a busy rehoming centre too distressing. The Dogs Trust, which manages the home, has had a surge in elderly dogs being delivered to its centres. Last year, of the 15,239 dogs taken in by the trust, one in 10 were eight or older. The charity hopes to rehome all of its residents eventually, because you can teach an old dog new tricks – just not too many.

Dogs Trust, Shrewsbury (01952 770225)

Greenspeak: Danger days {\’dān-jer dāez} noun

Times when going outside for exercise is risky, because of heat and humidity. Used to be rare, but thanks to global warming, it’s set to become a regular occurrence, particularly in US cities.

If you have an ethical dilemma, email Lucy at lucy.siegle@observer.co.uk

Follow Lucy on Twitter @lucysiegle