DNA recovered from skeletons buried in a 7th-century cemetery on the south coast of England has revealed that the buried individuals had west African ancestry, raising further questions about early medieval migrations to Europe.

Archaeologists documented significant migration during this period into England from continental northern Europe, with historical accounts describing the settlement of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.

However, the extent of movement from further afield has remained unclear.

To further understand early medieval migration in Europe, researchers performed DNA analysis on individuals buried at two 7th-century cemeteries on England’s south coast – at Updown in Kent, and Worth Matravers in Dorset.

The findings, published in two studies in the journal Antiquity, show clear signs of non-European ancestry in two buried individuals with an affinity to present-day groups living in sub-Saharan west Africa.

While most of the individuals buried at the cemeteries had either northern European or western British and Irish ancestry, one person at each cemetery had a recent ancestor from west Africa, scientists said.

“Kent has always been a conduit for influence from the adjacent continent, and this was particularly marked in the 6th century – what might be termed Kent’s ‘Frankish Phase,’” said Duncan Sayer, an author of one of the studies, from the University of Lancashire.

“Updown is also located near the royal centre of Finglesham, indicating that these connections were part of a wider royal network,” Dr Sayer added.

In contrast, Dorset was on the fringes of continental influence, researchers said.

“The archaeological evidence suggests a marked and notable cultural divide between Dorset and areas to the west, and the Anglo-Saxon-influenced areas to the east,” said Ceiridwen J Edwards, one of the authors of the other study, from the University of Huddersfield.

The individuals showed clear signs of non-European ancestry, and an affinity with present-day Yoruba, Mende, Mandenka, and Esan groups from sub-Saharan west Africa, the study noted. Further DNA analysis revealed that they were of mixed descent, with each having one paternal grandparent from west Africa.

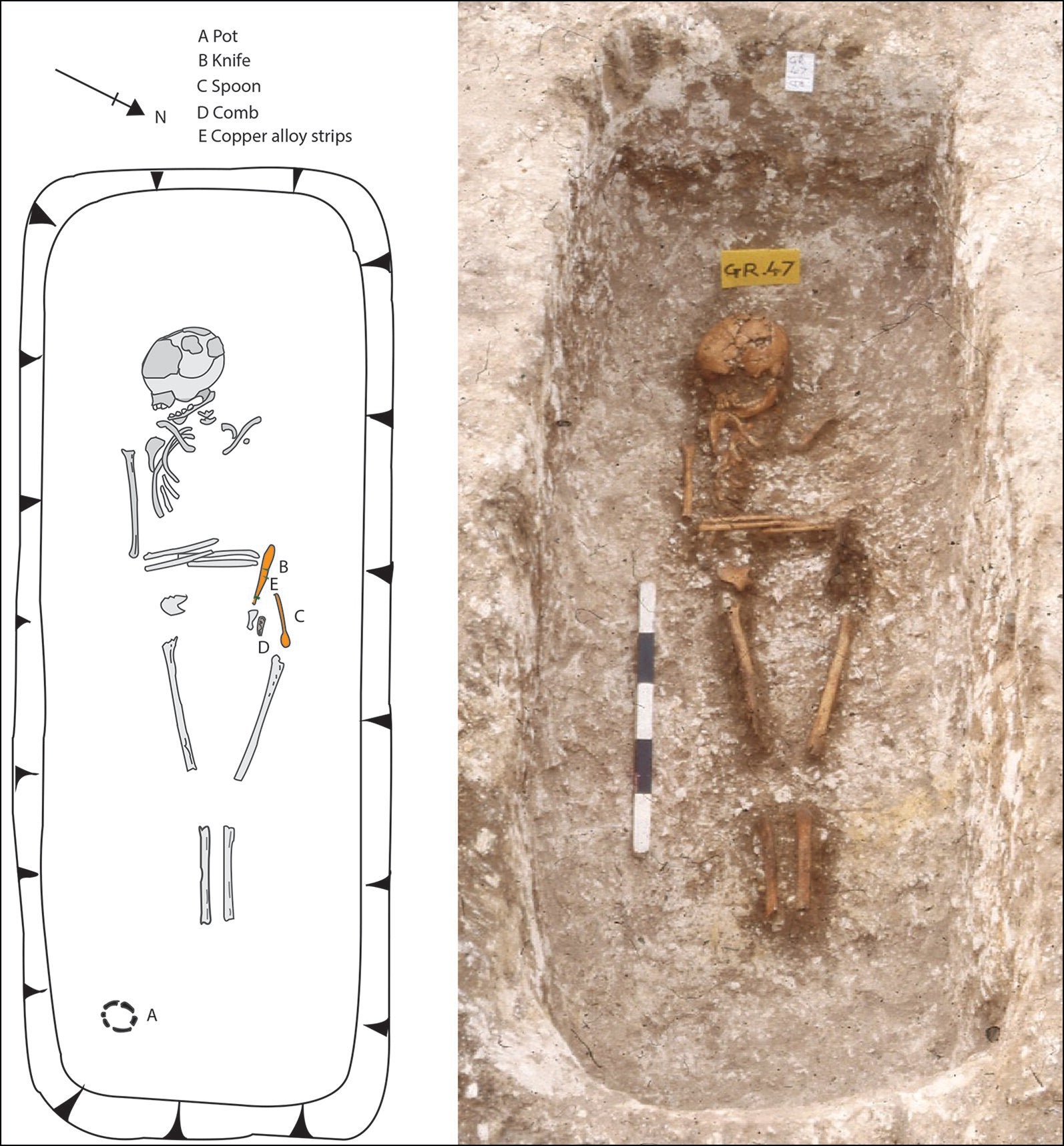

The Updown grave was found to contain several goods, including a pot likely imported from Frankish Gaul, and a spoon hinting at the individual’s Christian faith or connections with the Byzantine empire.

The cemetery was part of Kent’s royal network, and these grave goods and genetic indicators point to the region’s continental connections, the study noted.

The other individual at the Worth Matravers grave site was buried alongside a male with British ancestry, and an anchor made of local limestone.

The fact that the individuals were buried along with typical members of their communities indicates that they were valued locally, archaeologists noted.

“What is fascinating about these two individuals is that this international connection is found in both the east and west of Britain,” said Dr Sayer. “Updown is right in the centre of the early Anglo-Saxon cultural zone, and Worth Matravers, by contrast, is just outside its periphery in the sub-Roman west,” he explained.

The findings, according to researchers, raise further questions about long-distance movement and demographic interaction in Britain during the early Middle Ages.

“Our joint results emphasise the cosmopolitan nature of England in the early medieval period, pointing to a diverse population with far-flung connections who were, nonetheless, fully integrated into the fabric of daily life,” Dr Edwards concluded.

Sir David Attenborough names golden eagle chick hatched in Scotland

Hair strand stuck in ancient device could change what’s known about Inca civilisation

Human species that lived alongside our oldest ancestors discovered

DNA testing of 1,400-year-old skeletons reveals ethnic diversity of early England

Ancient stone tools found in Indonesia could unravel mystery of ‘hobbit’ humans

Turin Shroud imprint might not be from human body, study says