Several thousand years before the pyramids rose over ancient Egypt, people living on the Arabian Peninsula constructed a different kind of marvel. Called a mustatil, it was drastically different than a pyramid, arranged in a 2-dimensional rectangle and characterized by short walls and open courtyards.

Mustatils, named after the Arabic word for rectangle, were once extremely common across the landscape. The remains of over 1600 are known in Saudi Arabia today — though their purpose in the ancient world remains a mystery.

In the past few years, scientific surveys and excavations have finally started to bring these mysteries to light. One group of researchers from Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Switzerland have been digging into the past of a particular 7000-year-old mustatil to understand how it was used.

On Wednesday in the journal PLOS One, they describe new findings based on extensive excavations and analysis. Animal bones, ritual stones, and human burials reveal that the site was a place for cult sacrifice and pilgrimage — and may have served multiple roles over the centuries.

Common sight

The Saudi Arabian city of Al-’Ula (also stylized AlUla) is surrounded by the remains of mustatils. It represents just one of several regions on the northern Arabian Peninsula that is home to these unusual monuments.

Though musatils range in size from 20 to 600 meters in length, they have the same defining features: two long walls running parallel, with short head and base barriers at opposite ends. A narrow entryway in the base typically opened up to a large courtyard, while chambers were constructed at the head of the monument.

Some mustatils were constructed in lava fields from basalt, while others were made of desert pavement, clusters of stone that naturally form in arid climates.

People began to document the mustatils back in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until recent years that scientists first studied them in detail. Funding from the Saudi Royal Commission for AIUla, which was established in 2017, has supported large-scale surveys and excavations, including the one reported in the new study.

Melissa Kennedy, an archaeologist at the University of Western Australia, helped excavate one of the mustatils 55 kilometers (34 miles) east of Al-’Ula. Some initial discoveries were reported in a 2021 Antiquity paper, where Kennedy and colleagues described a host of animal bones and a sacred stone known as a betyl. But more were hidden within the walls, waiting to be discovered.

Site of sacrifice

The skull and horns of cattle, sheep, goats, and gazelle were all found at the site, buried around the betyl. Since betyls were part of many ancient religious practices, and were believed to connect humans with deities, Kennedy and colleagues interpreted the animal remains as part of a ritual sacrifice.

Whoever sacrificed the animals appeared to select only bones from the cranium, or the region of the skull that encases the brain. Horns, too, were a commonly buried object. But no teeth or jaws were unearthed during the excavation.

Kennedy tells Inverse that one of the new findings that was particularly surprising was the way these remains were prepared as offerings.

“Some of the horns had the bone cores removed, with just the keratin sheath preserved, whilst others had the bone core and the sheath prepared,” she says. “We don’t [know] why they were prepared in these different ways, but the fact that they were not all prepared in the same manner is really interesting.”

At this point, little is known about the details of the rituals that once took place there. Archaeologists sometimes look to written texts for a direct explanation, but only if they’re available. The mustatils predate the earliest known written language by thousands of years, so it’s unlikely such a document exists.

However, Kennedy says that finding nearby ancient settlements could potentially shed light on questions about the mustatils.

“We haven’t excavated any settlements associated with the construction of the mustatil, so these may hold further clues and information about the practices involved,” Kennedy says. “But we will only learn more through more excavation and research.”

Place of pilgrimage

Right now, many mustatils seem to exist as isolated spaces; the ones in Al-’Ula were far away from known settlements of the time. That’s part of the reason why the researchers believe that they may have been sites of pilgrimage, where ancient peoples would have traveled for religious ceremonies.

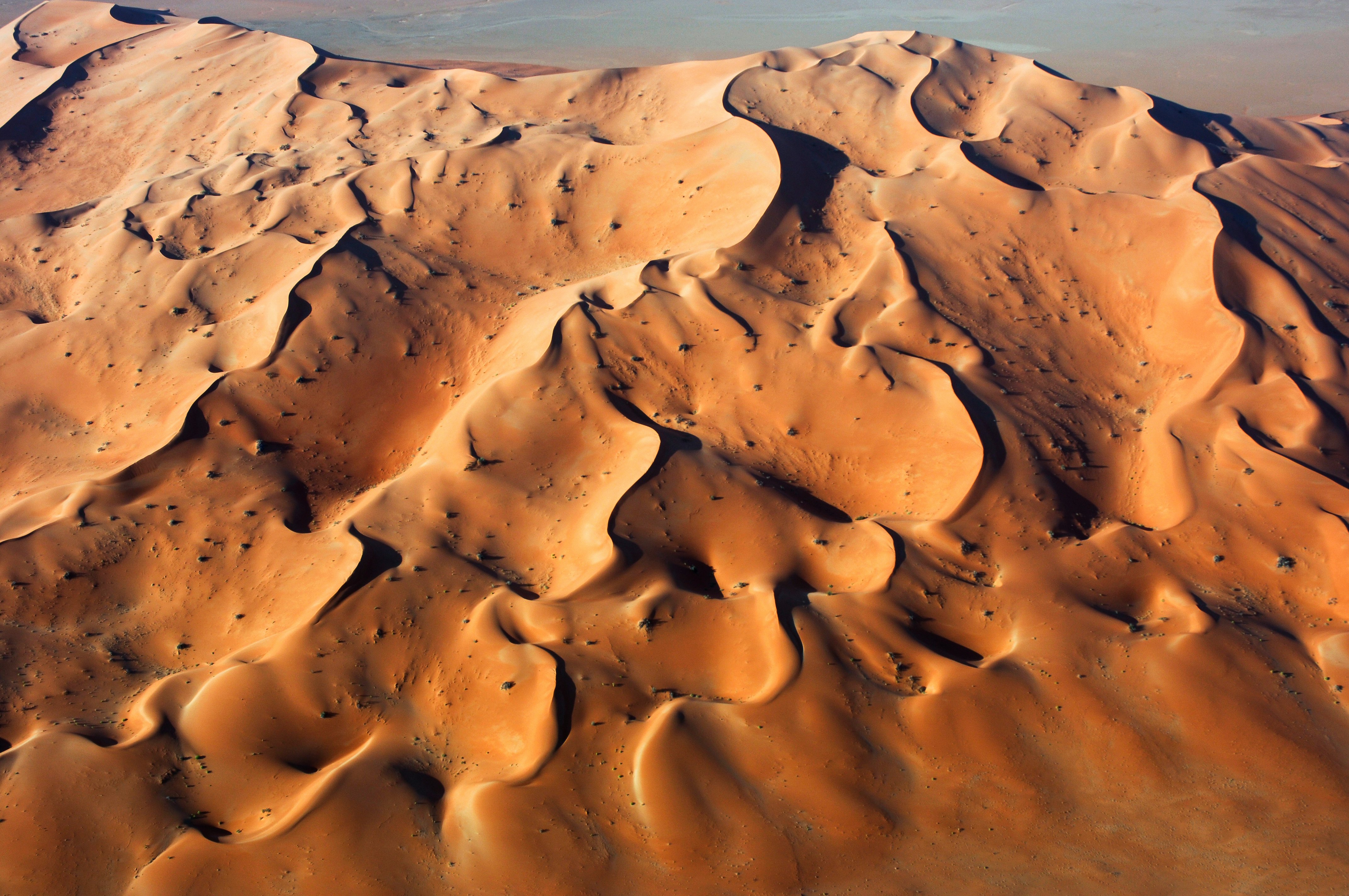

During the time when animal sacrifice was happening at the mustatils, the climate in Arabia was much different than today: 7,000 years ago, the Earth was in the Holocene Humid Period, a stretch of time where the landscape in Arabia saw more humidity and rain.

It’s likely that the mustatils had some connection to water, since many of them are near features like wadis (riverbeds that fill only during the rainy season) and playa (flat areas that become lakes during rainfall). It’s possible, the researchers write, that people could have made sacrifices to the gods for more rain during periods of drought.

But as time passed, the purpose of the mustatils seemed to shift. Human remains were found at the excavated mustatil for the first time — and Kennedy says researchers have found more evidence since that individuals were buried within the monuments.

An enduring tradition

While the animal remains show clear signs of sacrifice, the human remains do not. And the burials of humans always seem to come later than animals, Kennedy says — by about 400 years.

“I think what is most surprising is that these people date much later than the mustatils and that they represent a deliberate return or choice to reuse these structures for an entirely different purpose,” Kennedy says, “It shows us that the function and meaning of structures can change over time.”

While a single adult male was described in the new report, Kennedy explains that the remains of other people, ranging in age and sex, have been found at mustatils. No clear pattern appears to link who is buried there.

“We [hypothesize] that these sites retained their importance even after they stopped being used, and that later generations would bury their dead at these places as a way of asserting ownership over these structures, essentially claiming a link with the past,” Kennedy says.