A Roman Catholic priest in Alabama is under investigation, church officials say – and he abruptly announced he is taking “personal leave” – after a woman alleged to his superiors that he traded financial support for “private companionship” including sex, beginning when she was 17.

The accuser, Heather Jones, has also alleged that the clergyman, Robert Sullivan, recently paid her hundreds of thousands of dollars to remain silent about it, a claim she supported with bank records, an email and a copy of a legal agreement.

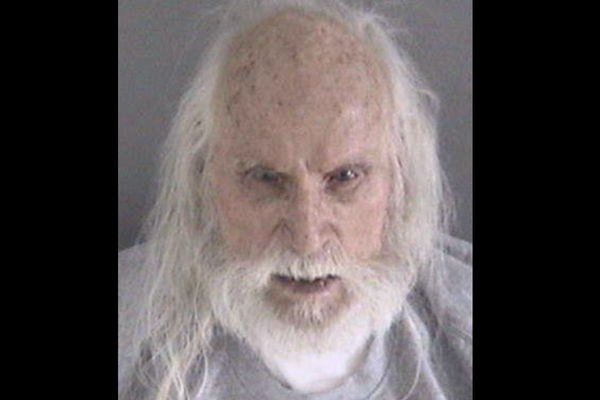

Jones, 33, provided the Guardian with a formal written statement that contained her allegations against Sullivan, 61, and which she provided to the diocese of Birmingham.

She said she came forward because Sullivan had continued working closely with families and their children as the pastor of Our Lady of Sorrows church in Homewood, Alabama, leaving her fearful that “others may be vulnerable to the same type of manipulation and exploitation” she says she endured.

Jones gave permission to be publicly identified by name, saying she hoped it would boost the credibility of her account.

Birmingham diocese spokesperson Donald Carson said on Tuesday that the allegations against Sullivan were under investigation by an independent review board advising the local church. As was its protocol, Carson said, the diocese had forwarded the allegations to the Vatican entity which investigates cases of clergy misconduct.

And Carson said Sullivan would be prohibited from public ministry until the resolution of the allegations against him.

Voicemails the diocese left with Jones – and which she shared with the Guardian – offered her free therapeutic counseling.

It was not immediately clear how much scrutiny Sullivan might draw from lay authorities. Carson said the diocese had reported Sullivan to the Alabama state agency that investigates child abuse cases because of the age Jones said she was when she met him. But officials at Alabama’s department of human resources had said the case did not fit the criteria of one in which they could get involved.

Law enforcement investigators have been reluctant to act in some cases of religious clergy accused of having sexual contact with teens who had reached the legal age of consent, which in Alabama is 16. Furthermore, Alabama is not among the US states with laws that say it is impossible for there to be consensual sexual relationships between clergy and legal adults who are under the clerics’ spiritual guidance.

Sullivan could, however, face consequences within the Catholic church. Canon law to which clergymen are subject has considered people younger than 18 to be minors – and sexual contact with them to be abusive – since the early 2000s, when the worldwide Catholic church implemented reforms amid the fallout of a decades-old clerical molestation scandal.

Multiple attempts by the Guardian to contact Sullivan for comment were not successful Tuesday.

As she wrote in her statement to the diocese in late July and recounted to the Guardian more recently, Jones grew up in foster care after being removed from her mother’s custody “due to severe neglect”. She wrote that she lacked “consistent adult support” during her upbringing, leaving her ill-equipped to maintain employment or pursue a formal education – so she tried to make ends meet by working as a dancer at an “adult establishment” outside Birmingham.

Jones said she was 17 when she met Sullivan at that establishment, which let her work there despite being under an applicable age limit. He was a regular patron, tipped her during her shifts and soon offered to “help change [her] life” if she called him on his phone number, she wrote.

Sullivan proposed “to form an ongoing relationship that would include financial support in exchange for private companionship”, wrote Jones, who told the Guardian that the term encompassed sex. Jones said Sullivan subsequently began taking her shopping, dining, drinking, and to hotel rooms in at least six different Alabama cities in part to engage in sex – beginning when she was 17 and over the course of several years.

Jones wrote that she “was a minor with no experience navigating adult relationships” when she met Sullivan. She wrote: “I was hesitant but ultimately agreed due to his persistence and the state [of mind] I was in.”

Jones said Sullivan bought her a phone on which he frequently contacted her. He initially presented himself as a “doctor”, though she later learned he was a priest while his brother was a physician, she said.

She wrote in her statement that discovering Sullivan belonged to the Catholic priesthood – whose members promise to be abstinent and teach that sex out of wedlock is sinful – was disturbing because she had attended church services throughout her youth and had difficulty reconciling “his public role and private behavior”.

Sullivan paid for Jones to attend a rehabilitation program after she experienced depression, emotional instability and addiction during their arrangement, she wrote.

Jones wrote that Sullivan and an attorney representing him eventually had her sign a non-disclosure agreement in return for $273,000.

She shared an unsigned copy of the NDA with the Guardian. She also provided a copy of a 27 March message from Sullivan’s Our Lady of Sorrows email address, which had the sentence: “Someone will be calling you to sign the NDA.”

Four days after that email, bank records which she shared with the Guardian showed, Jones received a wire transfer of $136,500 from an account under the name of the attorney’s law office. She received another $136,500 wire transfer from the same law office account a day later, the bank records indicated.

Separately, in more than 125 different transactions from 18 July 2024 to 26 March, a Venmo account under Sullivan’s name paid nearly $120,000 to Jones, according to a copy of records from the financial app that Jones shared with the Guardian.

Jones said it was never clear whether Sullivan took that money out of his personal finances, and remembered wondering whether it possibly came from some other source. Jones said he gave her the Venmo money of his own accord to aid her in covering her living expenses. Jones recalled Sullivan telling her he was also happy to give her that money because he loved her – and so did Jesus Christ.

Jones wrote that she later proposed to revise the NDA with Sullivan and requested $100,000 more. She said the agreement “heavily favored his interests and offered no meaningful protection, healing or justice” for dealings with Sullivan she had come to regard as “exploitative and predatory”.

Sullivan and his attorney ignored her, Jones wrote. She provided her statement to the Birmingham diocese a few days after writing it on 23 July. Jones said she was willing to share phone records and pictures which she contended would corroborate her version of events with church investigators if they sought the materials.

At Our Lady of Sorrows’ 3 August mass, Sullivan told his congregants that Birmingham bishop Steven Raica had authorized him to take “personal leave” that he requested after “prayer and reflection”.

“Please continue to remember me in your prayers – as I will do the same for you,” Sullivan said shortly before the conclusion of the mass.

On 10 August, Birmingham diocese vicar general Kevin Bazzel told congregants that Raica had appointed him as Our Lady of Sorrows’ temporary administrator in Sullivan’s absence.

Sullivan had in June celebrated the 32nd anniversary of his ordination into the priesthood. He had also served six years as president of Birmingham’s John Carroll Catholic high school and in 2023 was appointed director of its educational foundation, as the local Homewood Star newspaper previously reported.

He announced his leave nearly four years after Raica had appointed him to serve as one of the diocese’s vicars general, a high-ranking administrative post.

In 2020, Sullivan had appeared on the ABC show Good Morning America, in which he discussed recovering from Covid with a helping hand from his brother, an infectious diseases doctor.

Jones said she recently began law school and defied the NDA mentioned in her statement about Sullivan to the Birmingham diocese – which has an estimated membership of roughly a quarter of a million Catholics – because she was confident it would not hold up in court.

She also wrote that she considered it vital to speak out about Sullivan because “behind closed doors, his behavior toward me was not in alignment with the values he teaches”.

Raica said Wednesday in a diocesan letter reported on by the Alabama news outlets AL.com and WBRC that Sullivan had “a presumption of innocence until proven otherwise” as the investigations pending against him progressed.

Carson, the Birmingham diocese spokesperson, said the allegations against Sullivan were “unfortunate for all involved”.

“We keep father … Sullivan and the woman who’s making the allegations here certainly in our prayers,” Carson said.