To speak with Johnny Rozsa is a bit like hearing a movie script read aloud. Before he became an era-defining fashion photographer in 1980s London, Rozsa studied architecture, had a stint as a go-go dancer, interned at British Vogue, and ran a trailblazing vintage clothing store. It was only when he bought himself a Hasselblad camera in 1976, though, that Rozsa (the ‘zsa’ is pronounced like Zsa Zsa Gabor) discovered his true calling.

‘I just started shooting,’ he says. ‘I wasn't trained as a photographer, but I muddled through, and I made it.’

Rozsa swiftly became one of the most in-demand celebrity photographers of the time, working for magazines like i-D, The Face, and Vogue, and capturing arresting photos of Sade, Leigh Bowery, Boy George, Hugh Grant, Tina Turner (who introduced the photographer to Nichiren Buddhism in 1982) and many, many others.

Now, at 76, Rozsa—who is based in New York City these days—lives a quieter, albeit no less glamourous, life, with his pet dog and a circle of fashionable friends that includes Hamish Bowles and Jasper Conran. So it was a surprise when, after all his success as a photographer, Rozsa discovered a new creative outlet.

A few years ago, Rozsa began taking painting classes at the Art Students League with noted fashion illustrator Charles Nitzberg. Though he had painted as a child growing up in Nairobi, Kenya, (his Jewish parents moved there after narrowly avoiding the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia) Rozsa discovered a newfound kinship with the medium—one with surprising parallels to photography. ‘Fashion illustration is a dead art,’ he says. ‘If you look at Vogue in the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s, it was all illustrated. There were no photos.’

Rozsa’s Instagram page began to fill up with whimsical watercolour paintings— pretty rosy-cheeked ladies with umbrellas; friends and flowers; and even Rozsa himself.

‘When I discovered photography, you just take a picture and you can print it right away. That was my visual release,’ Rozsa explains. With painting, though, he’s rediscovered something deeper—more meditative. ‘I just got into this zone and I want to get into that zone all the time. It's so wonderful.’

Friends, and soon friends of friends, took notice. One evening at a party, Rozsa ran into Aziza Laraki, the founder and director of Gallery Kent in Tangier, Morocco. ‘She said, “Oh, you're the guy that does ladies with umbrellas. I have a gallery I'd love to show some of your work,’” Rozsa remembers. Though he was nervous, Rozsa agreed.

The result is ‘Compass Point,' a group show opening 10 July in Tangier that will feature dozens of Rozsa’s paintings, alongside work by New Zealand artist Sarah Guppy and UK-based artist Stephenie Bergman.

Tangier isn’t an arbitrary location for Rozsa; the photographer first visited Morocco as a student in the 1970s and has been visiting ever since with friends, notably with the English interior designer Veere Grenney. Now, the country has become something of a second home. ‘It’s such an interesting place. We met all these really interesting people with incredible taste,’ says Rozsa, who recalls catching glimpses of Yves Saint Laurent. ‘It’s a country of contrasts.’

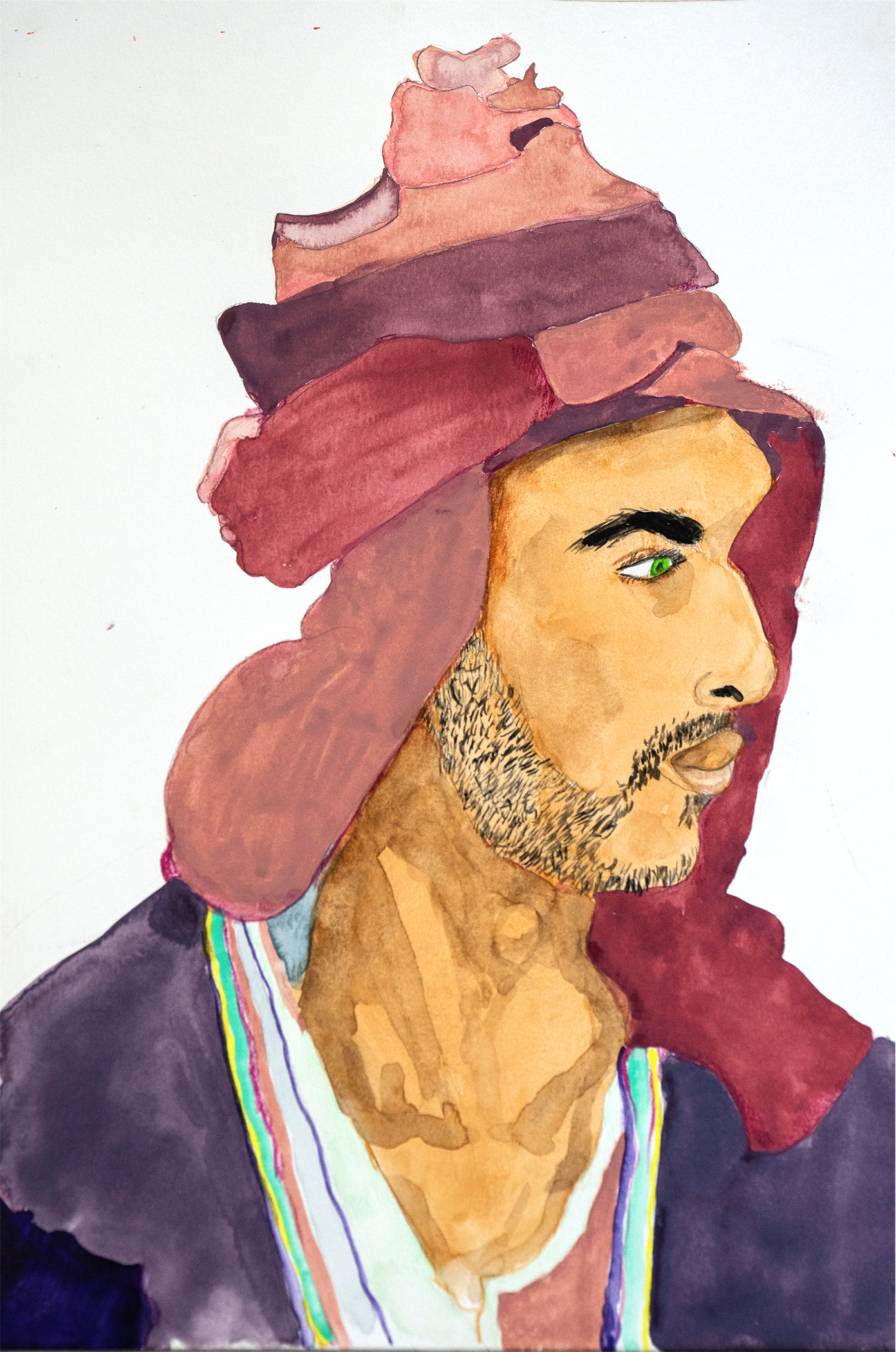

But he still didn’t know quite what to paint for his show. For inspiration, he paid a visit to the library of the American Legation Museum in Tangier, where a friend worked. Here, he discovered century-old photographs and illustrations documenting daily life and traditional clothing in Morocco and the surrounding region. Peter Hinwood, an antique dealer who is best known for his role in the 1975 film The Rocky Horror Picture Show, meanwhile shared a trove of early-20th century postcards depicting shepherds, mothers and children, and sex workers.

Rozsa found beauty in these forgotten images. He responded by reinterpreting them with personality, colour and narrative. Garments are awash in vibrant tones and faces, enlivened with Rozsa’s signature rosy cheeks, gaze directly at the viewer. He’s also given each painting a name, transforming them from anonymous subjects lost to history, to people with a story to tell. Rozsa doesn’t view them as documentarian or even fashion illustration—’I view them as art.’ And like Morocco, these whimsical paintings are about contrasts. ‘It's modern, but it's old; it's colorful, but it's black and white,’ he says.

He’ll be exhibiting close to 50 paintings as part of As part of Compass Point, some in custom palm-leaf frames. No surprise, many have sold well in advance of the opening. Also no surprise, Rozsa has already found inspiration for his next watercolour series: birds, which he plans to render in iridescent paint.

‘How lucky am I that someone's giving me an exhibition at this stage of my life?’ he reflects. ‘I just can't think of anything more pleasurable or creative. It's a blessing.’