Almost 60 years after former prime minister Harold Holt began to dismantle the White Australia Policy, The Neighbour at the Gate at Sydney’s National Art School Gallery presents a thoughtful examination of the consequences when good neighbours become good friends.

Street posters promoting the exhibition feature an image of a magpie. Advertising always distorts. Pardu (Tirritpa) by James Tylor, who has Kaurna and Mãori heritage, is a series of groupings of exquisite small bird daguerreotypes. Their shadowed silver surface gives the impression of antiquity, which is Tylor’s intention.

In Kaurna, the names of birds come from the songs they sing. This is also how birds are named in many Asian languages. Onomatopoeia makes a bridge between cultures. A QR code on the wall next to each grouped images of birds allows the viewer to hear blends of birdsong with human music.

Remembering the past

The visitor enters the exhibition through Imaginary Homelands, Jacky Cheng’s installation in the shape of a traditional Chinese paifang (牌坊).

The 1,110 strips of paper, with fragments of Chinese characters, represent a poem she learnt as child in Kuala Lumpur. But some of the language has been lost by the distortions of time. She now lives on Yawuru country (Broome), an Australian town with close links to many South East Asian cultures.

In remembering her past, she grasps elements of her Malay Chinese heritage.

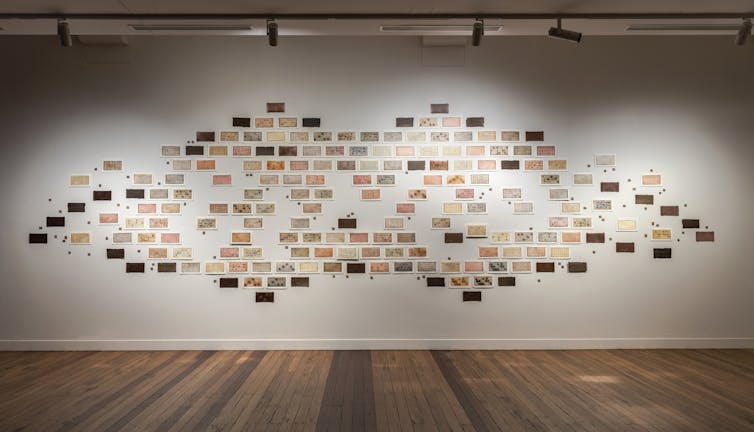

Dennis Golding’s Bingo is possibly as fragmented a memory as Cheng’s. Golding, a Kamilaroi/Gamilaraay man, has made a tribute to the community space his Nan and Aunty created in an abandoned terrace house in the Block at Redfern, where at night they would play bingo.

Each of the etchings scattered across the wall is the size of brick; each quotes small details of community life in Redfern before it was “discovered” by the gentrifiers. The exquisite etchings appear to be scattered at random, but a careful look will show the word “Bingo” in white in the spaces on the wall.

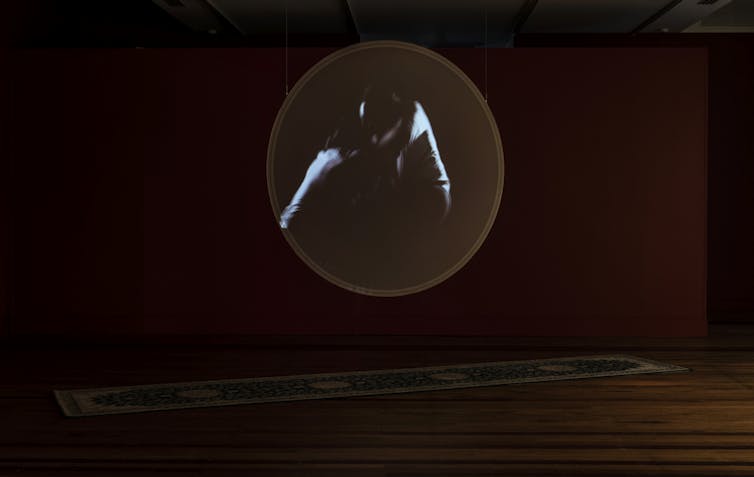

Elham Eshraghian-Haakansson’s God of War is a beautiful and sensual video on love, rage, reconciliation and the emotional journey of being a refugee.

Eshraghian-Haakansson is a second generation Iranian-Australian whose work is shaped in part by the experience of her mother and grandmother, whose Baha'i faith placed them in peril in 1979 after the Ayatollahs seized power. The different segments of this elegant video are deliberately broken by rough insertions, giving it a sense of a work reclaimed from history.

Along the water

Jenna Mayilema Lee’s complex installation in three parts is both a universal statement on the integration that is the long-term consequence of the meeting of cultures, and a personal statement on her own circumstances.

Each component – the photographic mural, the video and the billabong sculpture – can be seen as an independent work, but when combined they form magic.

Lee is truly a modern Australian, descended from Gulumerridjin (Larrakia), Wardaman, KarraJarri people as well as having Japanese, Filipino, Chinese and Anglo ancestors.

The lotus sculptures in the billabong are constructed from copies of immigration documentation. Her Chinese ancestors were living in Australia well before the White Australia policy of 1901. When they needed to travel, bureaucracy demanded multiple forms.

She has layered the forms with a hand print from one of her Japanese ancestors which, much to her pleasure, she discovered is the same size as her own hand.

The billabongs of northern Australia, especially in Larrakia country, are filled with lotus plants. The ancestors of the lotus plants of northern Australia floated across the narrow seas from Asia many years ago, in much the same way as people.

Water does not always bring life. James Nguyen’s Homeopathies_where new trees grow, is a reminder of another consequence of colonisation.

As with many other Vietnamese Australians, his family lives near the Parramatta and Duck rivers, west of central Sydney. One of the horrors of the Vietnam war was the way Agent Orange, destroyed both the jungle and the lives of people who came into contact with it.

Agent Orange was made by Union Carbide, near the Parramatta River. When the factory closed the contaminated site was not properly sealed and the poison seeped into the river.

Nguyen’s giant floating textile is of made of raw cotton and silk strips, dyed with mud and weeds contaminated by dioxin and Agent Orange. The evil of contamination is countered by clay pinchpot incense holders which line the stairs and entrances to the exhibition.

The cleansing smoke of incense is another link between the cultures of Asia and those of Australia’s First Nations people.

The Neighbour at the Gate is a generous and inclusive exhibition, a reminder of a common humanity. Clothilde Bullen, who heads the curatorium with Micheal Do and Zali Morgan, sees art as a way of countering divisions in society.

She told me:

If we are to work as a society and if we are to work as a community then we have to call people in, and we have to be prepared to embrace that difference. And so that is really what this show is all about.

The Neighbour at the Gate is at the National Art School Galleries, Sydney, until October 18.

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the Australian Research Council

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.