In 2022, when Hayden Christensen returned in the Disney+ series Obi-Wan Kenobi, he told me: “Back when we made those films [the Star Wars prequels], we didn’t really hear much from young fans. There was no social media. But now that they’ve grown up and have more of a voice, and the younger generations have been introduced to them, these films are seen differently.”

He’s got a point. But, by “seen differently,” Christensen argued that all the prequels, and perhaps Revenge of the Sith in particular, are now regarded as good rather than bad movies. But, for those who saw Revenge of the Sith at midnight on May 19, 2005, the issue wasn’t whether or not it was a good movie or not. Instead, there was one predominant and overriding sentiment that existed beyond value statements about the artistic and social quality of the movie: On no. This is the end of Star Wars.

If you’re a Zoomer, the prequels have always existed, and thanks to The Clone Wars and Dave Filoni, loving Revenge of the Sith has never been strange or shameful. This is all well and good, but for the Millennials/ Xennials who have always felt that Christiansen was a rock star, even though we didn’t have social media in 2005, the discourse around Sith, twenty years after its release, can feel strange. And that’s because if there’s one thing that has been truly lost in the conversation about the impact of Revenge of the Sith, it’s this notion of finality. Yes, that finality turned out to be temporary, but it certainly didn’t feel like it at the time. When Revenge of the Sith hit theaters, the sentiment was that this was the last Star Wars movie. For the generation who came of age with the prequels, the release of Revenge of the Sith was like the opposite of whatever our parents or cool older siblings felt when they saw the original movie for the first time in 1977. That generation, the younger Boomers and the older Gen-Xers, got hope.

For us, our most important Star Wars cinematic experience was a political and social tragedy, a sad opera designed to bum us out and warn us about how the Dark Side was always there, and no amount of magical “new hope” thinking could stop it. In a 2005 interview with 60 Minutes, when asked if George Lucas was taking audiences to Hell, in a Biblical sense, Lucas answered plainly: “Yes.”

The “Battle of the Heroes” ... stirs something almost primordial inside of us; much more powerful than anything that existed in the original trilogy.

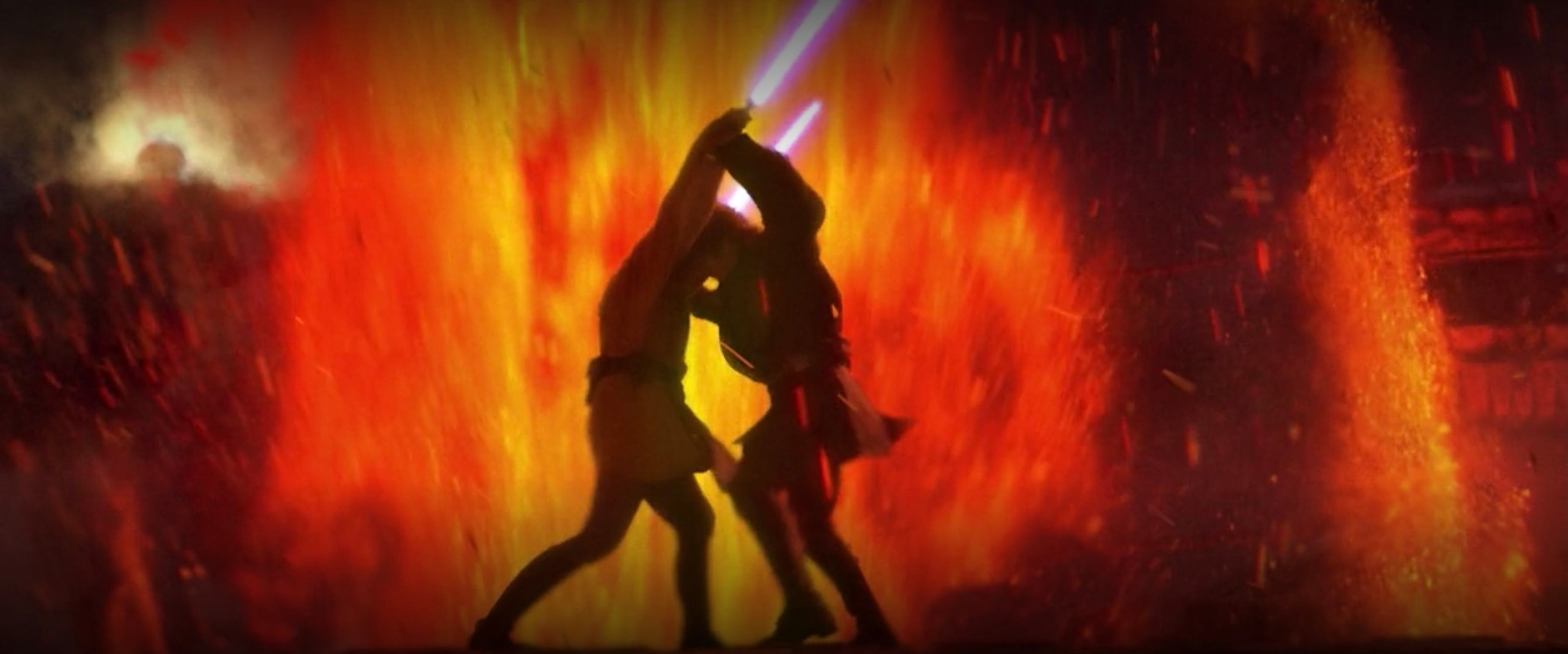

Relative to the film itself, Lucas was referring to the volcanic imagery during Obi-Wan Kenobi's (Ewan McGregor) and Anakin Skywalker’s (Hayden Christensen) final lightsaber duel on the planet Mustafar. For years, the lore on trading cards or in various Star Wars magazines had told us that Obi-Wan left Anakin in some lava, which disfigured him into Darth Vader. But what Lucas smartly did with Revenge of the Sith was to turn Anakin into a disciple of the Devil before he and Obi-Wan battled in Hell. For all the praise The Empire Strikes Back gets for being dark and serious, it's nowhere near as heavy-handed with its visual mythological imagery as Revenge of the Sith. This specific moment was later famously (or infamously) praised by controversial critic Camille Paglia in 2012 when she said, “How tepid contemporary art seemed compared to the passionate quality of this finale.”

This is the thing about Revenge of the Sith: its relevance and impact are bigger than memes about Obi-Wan having the high ground. More than any other Star Wars movie, the “Battle of the Heroes” between Obi-Wan and Anakin stirs something almost primordial inside of us; much more powerful than anything that existed in the original trilogy. Yes, Sith is a political and social film, but its strength isn’t that it was predictive, but rather the imagery feels oddly timeless, even if the whole lava/Hell thing is a bit much.

In a sense, Lucas’s profoundly unsubtle approach to Sith is what makes it such a compelling and interesting work of art. In numerous interviews about the creation of the first Star Wars, Lucas claimed he wanted to give the younger generation hope and a new kind of mythology. One wonders what Lucas hoped my generation was supposed to take from Revenge of the Sith. If the classic Star Wars movies freed Boomers and Gen-Xers from the mistakes of their parents, the prequels ended with the opposite message: We’re doomed. Darth Vader’s descent into darkness wasn’t a visit to Purgatory, it was a permanent, living Hell. And the proof was that the original movies already existed, forcing us to think differently about Darth Vader than ever before.

If the classic Star Wars movies freed Boomers and Gen-Xers from the mistakes of their parents, the prequels ended with the opposite message: We’re doomed

Armchair critics like to point out that Anakin's crimes in Sith make his redemption in Return of the Jedi absurd. But this misses the point of Lucas’s goals. Sith makes us think about Luke as the exception to the cycle of aggression and hate; Anakin’s existence is redeemed because Luke and Leia exist, not because we forgive Anakin. With Sith, Lucas made sure we never could. He doubled down on the evil of Darth Vader, a dark clarifying move worthy of Frank Herbert’s Dune Messiah. (Much of Anakin’s prescience and slide into darkness seems taken straight from that second, divisive Dune book)

Today, more time has passed since the release of Revenge than the wait between Return of the Jedi (1983) and The Phantom Menace (1999). The two prequels that followed The Phantom Menace — Attack of the Clones (2002) and Revenge of the Sith (2005) ‚ aren’t technically '90s movies, but relative to how culture feels now, versus then, they might as well be.

Sith was the Andor of its time; an edgier, darker Star Wars that, like the recently dropped Andor finale, only offered the existence of innocent infants as a ray of hope in what was otherwise a bleak, almost pathologically deterministic story. George Lucas was mercilessly mocked and memed for saying, “it’s like poetry, it rhymes,” relative to the reputation of visual tropes and motifs in Star Wars; but when Andor looked for a hopeful button to put on the end of its Les Misérables-ish story, it didn’t homage A New Hope, but instead, offered thematic and visual ending very similar to Revenge of the Sith.

But again, how this felt in 2005 is hard to fully relate to in 2025. If you’re among the set of fandom who believe Andor is the best of all Star Wars, then its final episode might be close to how everybody felt twenty years ago: The ending of something strange, sad, beautiful, and utterly irreplaceable. Star Wars, of course, continued after this movie. But for those who were there, we’ve never quite recovered from this moment.