No name in video games is as well-known as Hideo Kojima — the mastermind behind Metal Gear Solid, Zone of the Enders, Death Stranding, and more. Kojima’s impact on video games as a whole can’t be understated, and that’s largely because of both the success and continued thematic relevance of Metal Gear. It’s easy to laud most of the Metal Gear games, but one entry that tends to be disappointingly overlooked is Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker. The brilliant PSP game was a profound prequel that enhanced the narrative themes of the entire franchise and paved the way for what would come in The Phantom Pain.

Peace Walker occupies an interesting place in the series, as it’s technically both a prequel and a sequel all at once, following Big Boss ten years after the events of Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater. After leaving the United States, Big Boss has starts his own mercenary outfit in Colombia. After a mysterious paramilitary group called the “Peace Sentinels” appears in Costa Rica, with an absurd amount of firepower, the Costa Rican government appeals to Big Boss to help solve the situation — before a new battle between the East and West powers of the world is sparked.

While it might sound pedantic, the major narrative theme of Peace Walker is, in fact, peace. Metal Gear games have always dived headfirst into the ideas of military conflict, nuclear deterrence, and how global affairs leave the weakest of us behind. Peace Walker takes that idea a step further by directly commenting on the idea of “peace,” and how we need conflict in order to enforce it. Peace only happens when everyone has the strength to discourage others from fighting. But the only way to avoid conflict is to prove that you have the strength and military to stop everyone else.

That theme is then layered into the story of Big Boss himself, who created a mercenary company to fight for those who don’t have their own armies. But across Peace Walker, he learns that his noble aspirations to fight for others aren’t actually solving anything, and only leads to more conflict.

Despite being a fairly short game, Peace Walker has a fascinatingly complex story — heightened by one of the best casts ever seen in the Metal Gear franchise. While he’d appeared in the series earlier, this is where Kazuhira Miller really started to play a central role, and he’s a fantastic character with an arc that runs parallel to Big Boss’. Then there’s the lovable Paz, whose story would go on to be heartbreaking in later entries.

That digs into what’s truly remarkable about Peace Walker’s narrative, the extreme duality of it. The presentation of the game and tone is overtly cheerful and positive, which is an intentional misdirection meant to contrast with the intensely dark subject matter and direction of the story. This becomes even clearer when you play Ground Zeroes and The Phantom Pain, and are given further context into the reality of Peace Walker’s events. It’s extremely rare that a prequel game gets retroactively better when later games release, but Kojima made it happen.

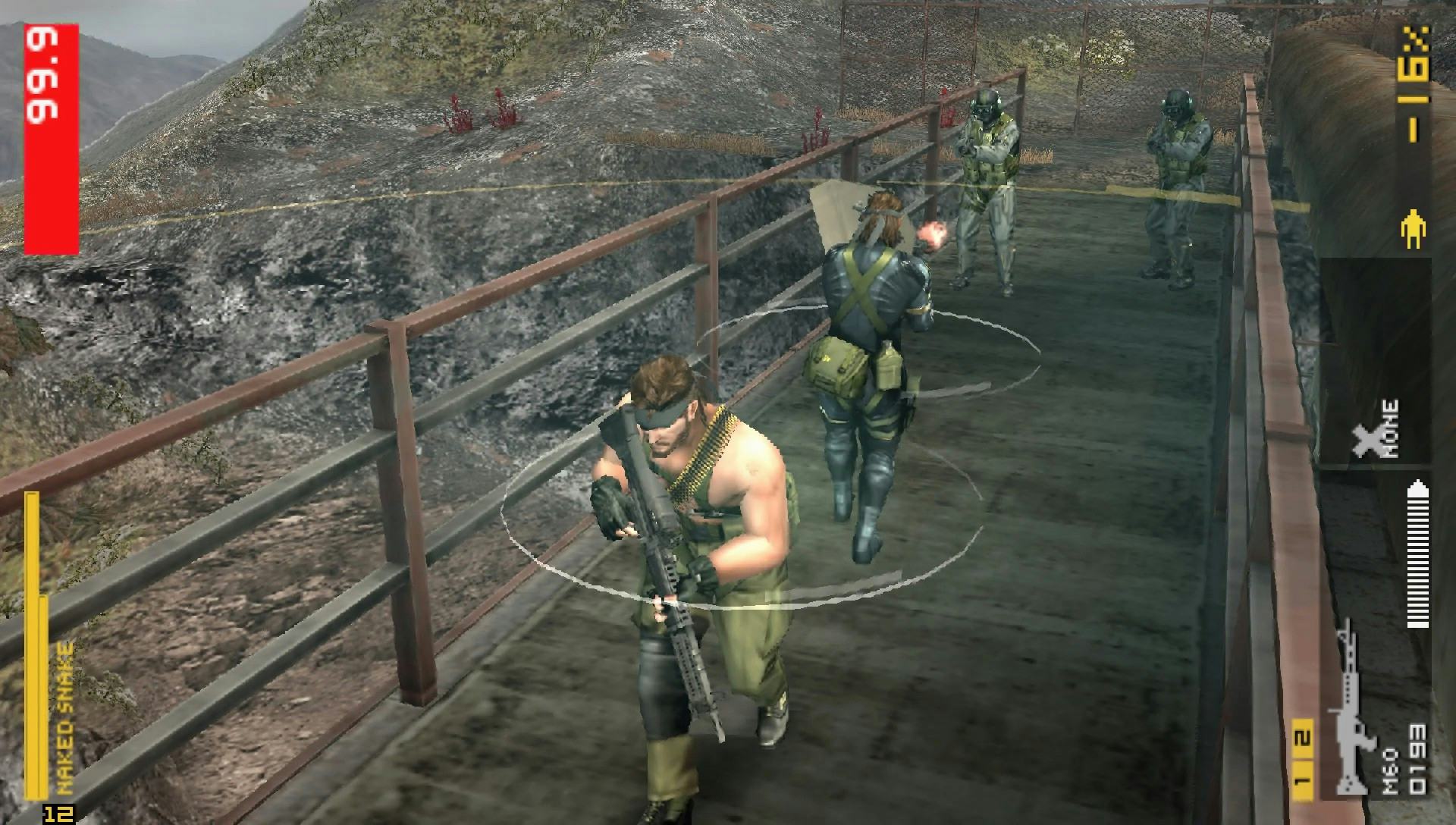

Of course, Peace Walker didn’t just lay the narrative groundwork for Metal Gear Solid 5, but also the mechanical one. Much like Phantom Pain, Peace Walker is essentially split into two gameplay halves — missions and Mother Base. The missions here are bite-sized action or stealth events, designed to take advantage of the PSP’s portability by giving you short bursts you can play at any time. The core stealth and gunplay of Peace Walker is essentially the same as Metal Gear Solid 4, but grafted onto a portable system. In this case, that’s not a bad thing — as MGS 4 nearly perfected the formula as it was.

In between those missions, you’ll spend a ton of time improving Mother Base and managing your soldiers. There’s a surprisingly deep management kind of minigame tucked into Peace Walker, where you can send your soldiers on Outer Ops missions, assign them to the mess hall to increase morale, and sometimes even have to send rebellious troops to the brig. It’s honestly astounding how much depth there is to the whole Mother Base system, and that’s before you even talk about side missions, different outfits for Big Boss, and co-op.

Peace Walker’s compelling mixture of tight and quick missions and deep management is a clear precursor to what Kojima would do in the Phantom Pain, on a much larger scale. The prequel almost feels like a condensed version of the bigger Metal Gear games, but that also allows its story to feel more vibrantly thematic. The way it not only embraces Metal Gear’s core themes but actually forwards the series’ message is nothing short of astounding.

The Phantom Pain quite literally wouldn’t exist without Peace Walker, and the portable spinoff has only aged like fine wine. It may not be Kojima’s most well-known work, but it’s easily one of his most compelling.