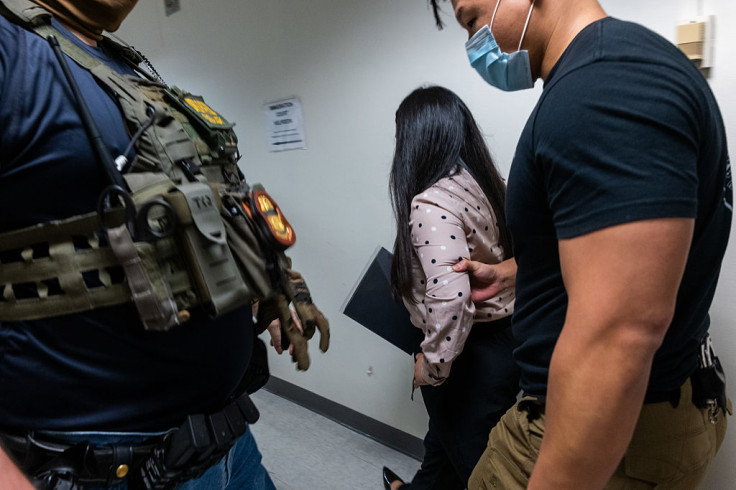

In an effort to meet arrest and deportation targets set by President Donald Trump after his return to the White House, federal immigration agents have for months been arresting people who show up for their routine immigration court hearings.

Beginning in May, reports from across the country described Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents waiting in courthouse hallways and arresting people as they exited their hearings. The tactic quickly drew criticism from immigration attorneys and advocacy groups, who warned it would discourage immigrants from appearing in court altogether.

As the practice spread to immigration courts nationwide over the past six months, a federal judge in San Francisco this week barred ICE from carrying out civil arrests at immigration courthouses across Northern and Central California, a decision that effectively restores restrictions that were in place in previous administrations.

In his ruling, U.S. District Judge P. Casey Pitts said the policy forces immigrants into an impossible dilemma, according to reporting by The Los Angeles Times. Individuals in removal proceedings, he wrote, must choose between attending court and risking immediate detention, or skipping their hearing and giving up their chance to pursue asylum or other forms of legal immigration status.

As reported by the outlet, the Dec. 24 ruling seeks to curb ICE activity in spaces long treated as "sensitive locations," including hospitals, houses of worship and schools, all of which have also seen reports of federal immigration enforcement actions.

The lawsuit was filed by a group of asylum seekers who were detained after complying with court requirements, The Los Angeles Times reported. One of the plaintiffs, a 24-year-old Guatemalan woman identified as Yulisa Alvarado Ambrocio, said she avoided detention only because her 11-month-old child accompanied her to court. Government attorneys told the judge that ICE would likely detain her at her next hearing.

Judge Pitts described the arrests as arbitrary and said they risk deterring people from attending their scheduled court hearings.

"That widespread civil arrests at immigration courts could have a chilling effect on noncitizens' attendance at removal proceedings (as common sense, the prior guidance, and the actual experience in immigration court since May 2025 make clear) and thereby undermine this central purpose is thus 'an important aspect of the problem' that ICE was required, but failed, to consider," Pitts wrote.

According to the Los Angeles Times, more than 50,000 asylum seekers have been ordered removed after missing court hearings since January, a figure that exceeds the total number of in-absentia removal orders issued over the previous five years combined.

Similarly, a former immigration judge who was dismissed from the Concord, California, immigration court in July told Border Report last month that the enforcement tactics have led many migrants to skip their hearings out of fear of being arrested.

"We had ICE officers in full tactical gear literally hiding in the stairwells of our court. Protesters gathered outside the building and clashed with ICE officials as they tried to block the vans carrying detainees. There was an overall climate of fear," Kyra S. Lilien said.

Before ICE increased arrests at immigration courts, Lilien estimated that roughly 85 percent of people appeared for their hearings. After courthouse detentions spread nationwide, she said attendance dropped to about 30 percent.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.