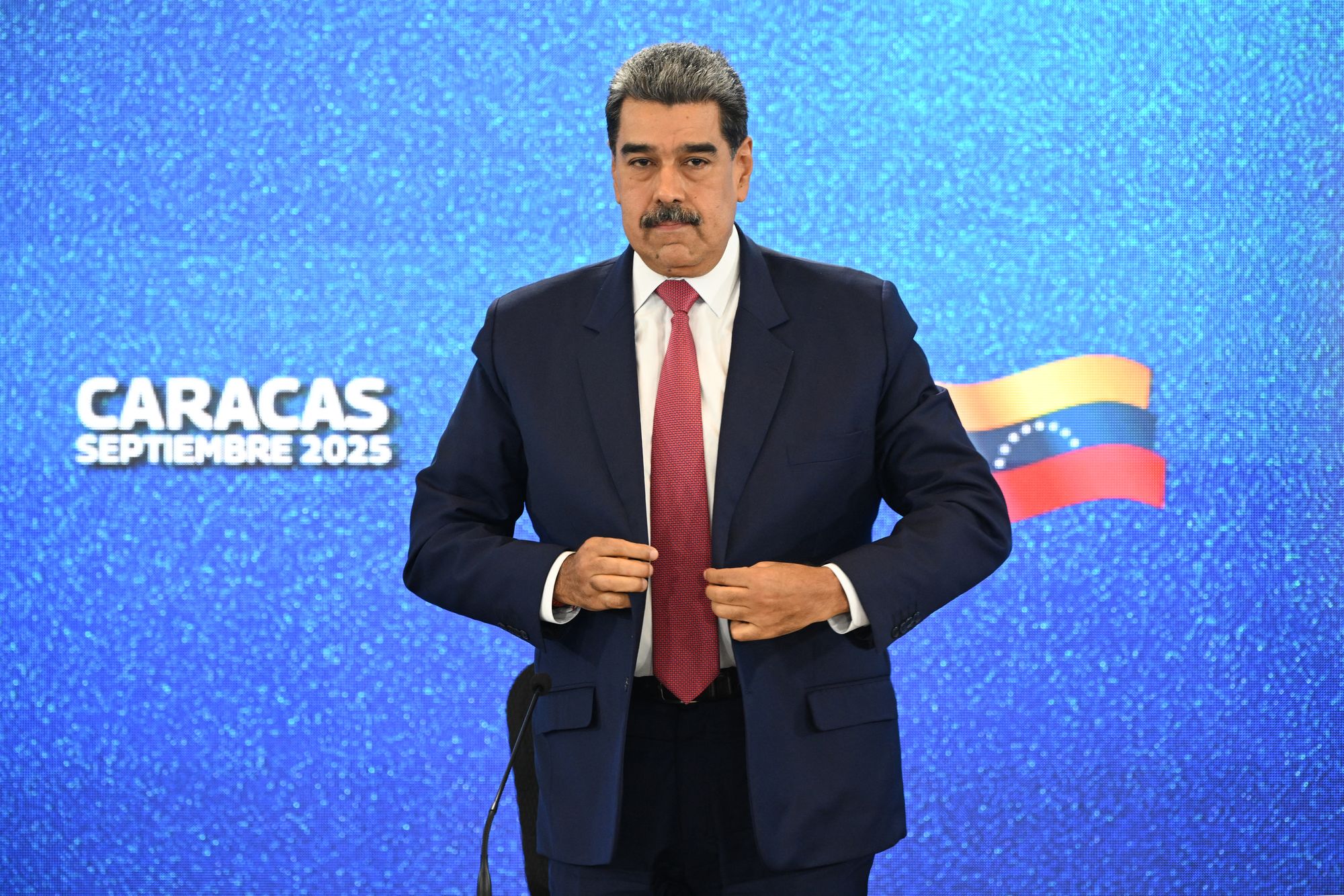

Donald Trump has ordered a “total and complete” blockade of sanctioned oil tankers from Venezuela as part of an ongoing pressure campaign against President Nicolas Maduro’s government.

Hundreds of U.S. troops and ships have been stationed near the Venezuelan coastline, where U.S. forces last week seized an oil tanker in the latest attempt to inflict economic damage on Caracas.

In a post on Truth Social on Tuesday, Trump boasted that Venezuela was “completely surrounded by the largest Armada ever assembled in the History of South America,” warning that “it will only get bigger.”

He demanded that Venezuela “return to the United States of America all of the Oil, Land, and other Assets that they previously stole from us.”

Caracas described Trump’s announcement as a “grotesque threat.”

How big are Venezuela’s oil reserves?

Venezuela has control over the largest known oil reserve in the world, producing around 1 million barrels a day.

Its oil reserves are found primarily in the Orinoco Belt, a region in the country’s east that covers around 55,000 sq km.

The country’s proven reserves are estimated at more than 303 billion barrels, which is the largest reserve worldwide — trumping Saudi Arabia’s 297.7 billion barrels.

Venezuela’s crude oil reserve is six times larger than that of the U.S., which, as of 2023, had 46 billion barrels.

In 2009, the United States Geological Survey estimated that the Orinoco Belt alone contained 900 to 1,400 billion barrels. Of this, it said that between 380 and 652 billion barrels were recoverable.

The belt holds heavy crude oil, which is harder and more expensive to extract than conventional oil. Advanced technology is required to produce usable oil from this region.

Why doesn’t Venezuela export more oil?

Despite its natural resources, Venezuelan exports stood at just $4.05bn in 2023, according to figures from the Observatory of Economic Complexity. This is a fraction of the $122bn exported by Russia, and $181bn by Saudi Arabia, in the same year.

Venezuela’s state-owned oil company PDVSA sells most of its exports at a steep discount on the black market in China — because the country has been locked out of global oil markets due to U.S. sanctions imposed by Trump.

Since the U.S. imposed its first energy sanctions on Venezuela in 2019, traders and refiners buying Venezuelan oil have resorted to using a “shadow fleet” of old tankers that disguise their location. The ownership of these vessels is often obscure, and they operate without standard insurance. Many have been sanctioned for transporting oil to Russia or Iran.

As of last week, more than 30 of the 80 ships in Venezuelan waters or approaching the country were under U.S. sanctions, according to data compiled by TankerTrackers.com.

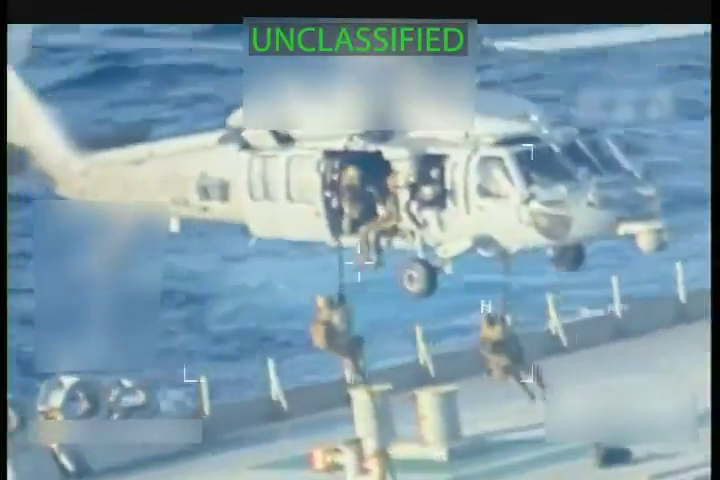

Last week, the U.S. intercepted a vessel called the Skipper off the Venezuelan coast — the first time Washington has captured Venezuelan oil cargo since sanctions were imposed.

Where is the oil exported to and what routes are used?

Francisco Monaldi, a Venezuelan oil expert at Rice University in Houston, said that about 850,000 barrels of the 1 million produced daily are exported. Around 80 per cent of that oil goes to China, 15 to 17 per cent goes to the U.S., and the remainder goes to Cuba.

Venezuelan oil is loaded at port terminals on its north Caribbean coast, such as the Puerto Jose.

Without a U.S. blockade, Venezuelan ships have direct access to the Atlantic Ocean, meaning they can travel to South Africa, then across the Indian Ocean towards China.

Tankers travelling to the U.S. will advance north through the Caribbean Sea towards the Gulf of Mexico, before they are unloaded at U.S. Gulf Coast ports including Pascagoula (Mississippi), St Charles (Louisiana), and Freeport (Texas).

Although the Trump administration has said the Skipper was heading for Cuba, analysts believe it was likely destined for China given its sheer size. The vessel, which is 20 years old, can carry around 2 million barrels of oil.

Why does Trump want to block oil exports?

The Trump administration has been ramping up tensions with Venezuela in recent months, with growing signs that the U.S. President is pushing for regime change.

The U.S. military has recently carried out a series of military strikes on Venezuelan boats in international waters in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific, which it claimed — without evidence — were carrying drugs to the U.S.

However, Trump’s chief of staff Susie Wiles appeared to suggest that ousting Maduro was also an aim for Trump, in an interview with Vanity Fair.

Trump “wants to keep on blowing boats up until Maduro cries uncle,” said Wiles.

The amount of crude oil that Venezuela has been able to export to the U.S. has since significantly dwindled.

Regime change in Venezuela, in favour of a president more aligned with U.S. interests, would provide Washington with increased access to Venezuelan crude oil, which is cheaper than crude oil from other countries due to its dense, viscous nature.

It could allow major U.S. oil companies, including Chevron — which already produces oil in Venezuela — to expand their operations in the country. This would allow the U.S. to reduce its reliance on oil from the Middle East and Russia.

It would also be a strategic win on the geopolitical stage, with Maduro currently allied with many of the U.S.’s adversaries, including China, Iran and Russia.

Ranchers in Texas are turning against Trump as price of beef plummets

Stocks rise as inflation dips and oil price rebounds

Trump-appointed judge argues noncitizens don’t have Constitutional rights

Federal appeals court allows National Guard deployment in Washington to continue for now

Megyn Kelly takes credit for arranging ‘detente’ between Candace Owens and Erika Kirk

MTG says MAGA is crumbling and ‘dam is breaking’ against Trump