Over the past two decades, Ryan Lee West – better known as Rival Consoles – has patiently perfected a brand of immersive electronica that conjures drama and emotion from filmic, synth-driven soundscapes.

Since becoming the first signing to influential label Erased Tapes in 2007, now home to post-classical darlings Nils Frahm and Ólafur Arnalds, West has steadily maintained a prolific solo output while finding the time to lend his talents to both video games and television, notably scoring a Black Mirror episode in 2019.

Ahead of his latest project, though, West ran into a frustrating period of creative block that demanded an entirely different approach. The solution was to escape the studio altogether, playfully piecing tracks together on the sofa and in hotel rooms, away from the collection of analogue synthesizers that have defined the sound of his previous output. (West is known for his love of the Prophet ‘08, going so far as to claim that 90% of the music he’s made has employed the instrument.)

The result, Landscape from Memory, is a collage of sounds that marries the synth-led sound design West is known for with digital textures and a scrapbook of discarded audio snippets collected over several years. Grand in scope and ambition but streaked with subtle, painterly details, the project is West’s most diverse yet, its musical narrative spanning celestial ambience, hypnotic arpeggios and surging rhythms across fourteen breathtaking tracks.

We sat down with West following the album’s release to find out more about how the project was made.

Hi Ryan. Can you take us back to when the work on the album began?

“Some tracks go back a long time. I sketched up Catherine five years ago. There are these melodic ideas that are sketched out and then almost abandoned, because perhaps I didn't know what to do with them at the time. There's a lot of work that was made very intuitively in the moment, and then some pieces were made over a long period of time because I was collaging and exploring different ways of working with them.

“There’s a whole world behind the making of the record, in a way, and there’s a huge amount of things that are explored that don’t make it in but are still interesting. It’s a huge amount of research; I use the word research because it feels like it's just a process of constant, ongoing research into writing music and exploring sound.”

The press materials mention some “discarded audio snippets” that were the foundation of the record.

“I make thousands of pieces of music, and there's no pressure on any piece of music to become ‘a song’, so it means that I end up with huge amounts of work, or research. And then there are these moments where perhaps two pieces, over a gap in time, can collide and be quite interesting together.

“That happened with Catherine, where it originally was an ambient piece of music, but then because of an accident, it almost started to have a kind of Four Tet, leftfield UK garage quality. But again, not quite, because I've never really made music for a club. It’s always more towards the songwriting side of electronic music.”

Developing so many ideas over such a long stretch of time, is it an organizational challenge to wrestle with that much material?

“It is difficult. It takes a huge amount of discipline. But it's one of those things where the things that listen after listen still affect you or move you, they're the ones that you pay attention to and stay in your mind. So the stronger ideas continue to get your attention. And so it almost doesn't matter if you feel a little bit overwhelmed by the amount of work, because the integral ideas tend to become the louder moments.”

Are these two completely distinct processes for you, generating ideas and then coming back later to edit and arrange them into finished tracks?

“Yeah, I do a lot of listening. It sounds ridiculous, but I could listen to an idea for a year and not do anything, and then the next year start making changes, because I’m working on multiple things at once. So there's no pressure to make something work in the moment, which frees up a lot of things, but creates other problems, mainly because of the abundance of material.

“There's almost no pressure for any given thing to work as well as I'd want it in my head, so I bounce between lots of different works simultaneously. And obviously they can influence each other, or I could learn something in one that would make me reconsider an aspect of another track. There’s a lot of feedback.”

The press release mentioned that some of the tracks were written outside of your usual studio environment. What motivated you to work elsewhere on this project?

“I was in a bad mental health state, and a bit burnt out, and just sitting anywhere – let’s say, on the sofa – with a laptop, feels so non-work that it lends itself to being more creative. I never want making music to feel like work. It’s the simplicity of thinking about music away from devices that you're used to, as well. You think differently when you're relaxed like that, and magical things can happen in those circumstances.

“I find that when you're in a professional kind of environment, all of a sudden you're not as relaxed, unconsciously. Obviously everyone's different in that respect, but I find that unconsciously I feel a certain narrowing of things, and I'm much more playful away from studios, for example. Even just traveling on tour, being in a hotel room in the morning if there's a few hours to kill, and I'm just messing around with very simple building blocks, but interesting things start to happen because there's no expectation.”

So most of the material was written on the laptop?

“It was mostly made on the laptop, but later on in the process I re-recorded some moments and strengthened some ideas in the studio. So there was a back-and-forth, especially towards the end.

“Thinking about the fact that I was listening out of a laptop, as well; for me to get excited by that, the composition has to have quite a lot of strength versus playing something through massive speakers, when the most insignificant thing can sound so powerful. There’s a weird tension between those two polarities, because obviously you can overlook simple things if you’re listening on laptop speakers. There’s an interesting learning experience between those two worlds.”

Working away from the studio, I imagine more of the sounds on the record were generated in-the-box?

“There’s a lot more digital plugin stuff going on. What it meant was that there was a newer aesthetic that was bound with a more analogue aesthetic, so you get a nice contrast. You can hear it especially in tracks like Gaivotas where you’ve got these fluttering, crisp, very digital layers going on, but contrasted by an acoustic guitar playing a few notes recorded in a very DIY way.

“They’re just miles apart, because one’s super precise and one’s very naive, and there’s all these contrasts between the colourization of the digital world and the more murky, rough analogue world. There’s definitely a blend between the two, and I use those digital moments mostly for contrast.”

Can you talk us through a few plugins that you used the most frequently across the project?

“It sounds ridiculous because I’ve been using the Prophet for a million years, but the Repro-5, which is a Prophet emulation. I find that I use that quite a lot, even though you would think ‘well, why?’, but you end up doing different things with a plugin versus a hardware synth, even if they’re relatively similar. Gaivotas was made using quite a lot of Omnisphere, which always gets a few laughs because it looks like it was made a thousand years ago now, but I find it’s actually amazing for certain things.

"You end up doing different things with a plugin versus a hardware synth, even if they’re relatively similar"

“Some people, when they first start making electronic music they judge a sound by itself, but actually a lot of the time when layering sounds, something that actually is a little bit not to your taste can be really magical – and to your taste – in combination with another sound. So there’s a lot of deeper considerations going on, but I'm not forcing this to happen. Accidents are happening, these exciting moments when two very different sounds occur at the same time and they become more interesting.

“What else have I been using? There's definitely some Ableton Operator. I find I often get really beautiful sine tones from that which a lot of people perhaps overlook. You know, everyone's probably seduced by sophisticated instruments like Serum 2, and I just mentioned Omnisphere, which is ridiculous. But I like both ends of the spectrum, like an overwritten Omnisphere preset versus Operator playing its initial sine wave, and everything in between.

“I’m probably forgetting some stuff. There’s some Slate + Ash stuff in Kontakt, a lot of the atmospheric stuff like Landforms. I didn’t use Cycles much on this. I basically use them completely in the background to add some depth, it’s not really foreground material.”

It’s interesting that Repro-5, a plugin version of a hardware synth that on the face of it is meant to be the same instrument, compels you to use it in a completely different way.

“I find that they're nothing like each other, in a way. If I was to just go and play on the Rev2 – I know Repro isn’t exactly modeled on a Rev2, it's more like a Prophet-5, obviously – but I would never do anything remotely the same with the two different types. I get some really interesting moments from those two different worlds.”

How about effects?

“Unfiltered Audio Biome, it’s a multi-effects unit. That’s amazing for creating very nuanced flickering effects; something very crude could go into that and it can become very textured and fragmented. I like moments like that, again, often in the background.

“I'm still a sucker for Valhalla Plate because, for some reason, I always want to put synths through plate reverbs or spring reverbs more than any other. I don't really like realistic reverbs for synths, and that might be because a plate reverb adds an artifact that makes it somehow a little bit more realistic-sounding, weirdly enough. Whereas putting a synth through a very realistic convolution reverb, you really notice there's a contrast between the two worlds.

“There are many instances where it's 100% plate reverb on the synth sound, not a return channel, and it just sounds so interesting to me, because you get this weird metallic resonant quality. Any kind of Prophet synth sound into a plate reverb is incredible, and it seems like not many people do it. It seems like you don't really hear crude, overly metallic reverb sounds at the minute, it feels like you hear everything else, but maybe that'll come back around.”

Do you ever do any reamping with your synths, or anything in that realm?

“Kind of. There’s a lot of stuff recorded on to tape with a microphone, pitched on tape and then recorded back in. That's kind of a more extreme version of reamping, because you're actually changing the dimensions of the room as well. Because obviously, if you record a melody with a microphone onto tape and then drop it half speed, because it's picking up the room, it's changing the sensation of the room as well as the actual melody.

“For the chorus of In Reverse, I took the whole song and vocoded that by itself. As in, the rhythmic values of the song then vocoded a chord progression, and then that was added back in. It’s quite interesting, if you were to just isolate that vocoded synth line, it is the whole song driven through that and then placed back into the track. It’s a bit weird, it’s almost like a chicken and egg situation.”

“When I'm doing these things, I'm never really expecting anything to work, and then there are just these moments where something magical happens. It's just a crude sort of exploration, like ‘oh, what would happen if…?’ I’m just smashing through ideas and now and again, something emerges that's quite useful. But it could be something that's useful for another composition, so there's a constant exchange of ideas.”

Did you use many pedals on the album?

“A lot of pedals, especially for ambient, complementary layers. I used the Chroma Console a lot on this album, which I didn't expect to. I thought I would kind of like it, because I never expect anything to be like, ‘wow, that's definitely going to be used on loads of songs now’, but it just did. It instantly did. There are some really beautiful moments on the record where that was used.”

That’s the multi-effects pedal from Hologram Electronics?

“Yeah. There are four layers of effects, and on each layer you have different options. It’s quite a nice way of adding 10% of this, 5% of that, 20% of something else, and you end up with a much more coloured, enhanced and ‘finished’ sound versus if you bypass it. There's a sound in Nocturne which is really fucked up, like this beautiful melodic synth sound that's really falling apart, and I find that really amazing. It's the kind of melodic line that would be absolutely boring without this set of processing. It’s like a Grade 1 guitar solo, like three notes, but all of a sudden it becomes interesting through this malfunctioning effect.

“The opening pads on Nocturne took ages to make, because that was actually a giant 10-minute mono recording that I recorded through Z.VEX’s Instant LoFi Junky pedal into a Roland Space Echo. And then two years later, I started playing little sections of it forwards and backwards in Ableton’s Sampler, like two to three seconds, and then I built up loads of instances of that, and each one's a different pitch. And then I formed a new song from playing forwards and backwards through this giant recording. For some reason, I think it's one of the best synth sounds I've ever made. It sounds like ocean waves, but in a really natural way, undulating backwards and forwards.”

In terms of hardware synths, what featured most prominently on this project?

“The Prophet Rev2 was used a lot. The Moog was used quite a lot, especially on Soft Gradient Beckons, which has this huge, clicky, very colourful but almost industrial synth sound. That’s really just two monophonic recordings, and it’s just the biggest sound ever. I played that in Berghain, that ambient piece. It’s quite anti-Berghain in a way, but the power and euphoria of it is quite interesting.”

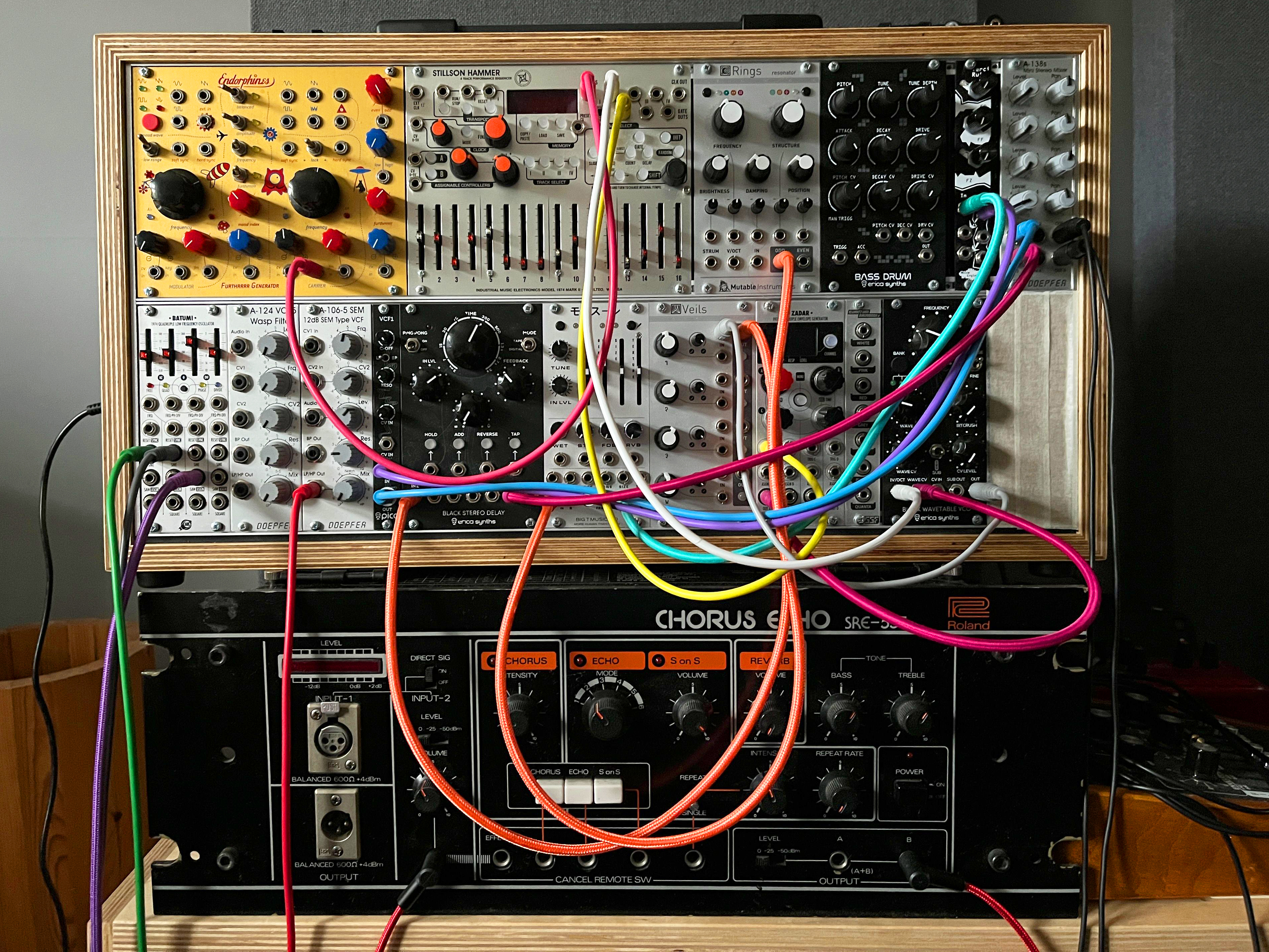

Where are you at with your modular set-up these days? Did that get a look-in?

“Not really. I don’t force anything to be there if it’s not doing anything interesting. I just got the Make Noise Strega, actually, and that’s amazing. The YouTube examples don’t really show how amazing it is. Alessandro Cortini uses just two of those live, and it’s incredible; a whole 70-minute set from just two Stregas and two sequencers, and he’s going between the two. I love that idea, making an hour of music from two monophonic melodic lines. I’ll probably use the Strega on future records. I’m not really answering the question, but I’m really interested in the Cric as well, have you seen that?”

Is that Future Sound Systems?

“Yes - that’s incredible, I played on that recently at a synth expo. I’ve never heard anything like it, especially for almost reamped-sounding, fucked up distortions that almost sound like you’re running something through a Marshall stack, but it’s all internal. That’s very good for more textured, gritty, Nine Inch Nails-sounding things. But there’s a lot. There’s too many things in the world right now, obviously, both physical and digital. It must be completely overwhelming for someone that’s just started making music.”

As fun as it is, all that stuff can become a major distraction from what you’re trying to achieve.

“Well, the thing is - do we even know what we’re trying to do? That’s the problem. I don’t think many people actually really know what they want to do. It’s a bit ridiculous to have in your head, like: ‘I definitely want to do exactly this thing’, and then you go about it. Most people just have a taste for things, and then they drift around aesthetics and styles and approaches to writing. But there are definitely too many distractions for younger people.

“It’s a bit different for me, because when I started I felt like there was absolutely nothing. It felt like there was just the Microkorg, and the synths that came before that were just for rich people. And then there were like, five plugins or something. I know that wasn’t the case, but that’s how it felt.

“And now, obviously, it’s the opposite. It feels like anyone right now could go on YouTube and type anything in, from popular to extremely niche, and you’d get a tutorial about how to do that, with almost any given piece of equipment. That’s a really good thing, but also, it’s perhaps sometimes good to be clueless and be a bit idiotic when you’re learning, kind of blindly stumbling towards results, which is what I did for a long time. My learning was very slow.”

I suppose that too much guidance can risk sending you down a predetermined path and without it, you’re forced to figure out your own voice.

“That's another danger as well. We live in a time where you can instantly have incredible sounds that are made for you by people that are very good at what they're doing, and that, again, wasn't so much of a thing in the past. I've always been a fan of making sounds that are your own; they might not sound as good as something professional but they’re more expressive.

"The snare drum in that song is the sound of ice cracking"

“Not only that, but people are seduced by big sounds – obviously because they’re powerful – but once you start working with these powerful sounds, you actually limit the creativity of what you're capable of writing with. If you start with lots of small sounds – small, weak drum sounds, for example – there's so much space for you to write expressively around those, whereas when you have these very big, powerful sounds, you’re limited by them. There are so many more things you can do around small sounds. It sounds like a ridiculous thing to say but I think that's really important.

“A lot of people might just instantly drag in huge-sounding things and keep them loud, but then where is the space? I definitely think it's worth recording your own lo-fi drum sounds and experimenting with that. It might even give way to you writing melodic parts that are way more interesting to you, and then you can bring those back to maybe powerful sounds. I find that all these different ways of writing can change everything.”

I was going to ask about your drum sounds. On the song If Not Now, it sounds as if you’ve pieced together little found sounds to create these intricate patterns.

“The snare drum in that song is the sound of ice cracking. It’s got this weird, knocky, textured sound, it almost sounds like brushes. The kick drum is something I recorded years ago, it’s a very dark, muffled, exaggerated but natural kick drum sound; I would never make it again the same, because it’s probably gone through multiple rounds of processing over the years. That combined with these cut-up foley sounds of ice cracking created a really interesting texture. I do a lot of that; really rough lo-fi drum recordings combined with a more pristine sort of drum sound to give contrast. I don’t like things to sound too precise.”

Are you just arranging these audio clips on the timeline, or are you using a sequencer or drum machine?

“I tend to always use audio in the timeline in a quite old-fashioned way, but there are also drum machines on the record. The claps in Coda are the classic 808 claps, but run through loads of pedals, so they're a bit phase-y, a bit weird and overly compressed, so they almost don't resemble 808 claps in the end.

“I quite like clicky, wooden sounds with a certain kind of knock, there’s lots of that going on, even in Coda again. Drum Song has so many different clicky sounds going on throughout it. Actually, the synth sounds in Drum Song are derived from drum patterns. That's why it's called that. Those rhythmic synth lines were drums first, and I used them to trigger these very small chord fragments, then the drums became invisible.”

I wanted to ask about Tape Loop; for me, that’s one of the most evocative tracks on the record.

“That’s an interesting one, because it’s that classic thing where you take something that sounds nothing like the finished piece, force it to be twice as fast so that you can record it into tape, and then obviously drop it an octave, which is also making it twice as slow, and then you get this eerie, weird sensation.

“Again, it's what I just mentioned before, because you’re using a microphone versus if you just line in – this is the key thing for tape that people might overlook – it's important to record the microphone, because then you're changing the dimensions of the room, the signature of the room that’s imprinted onto the recording. When that’s slowed down, you get such an unnatural, weird, hazy result.

“I know this is super obvious as well, because people have been doing this for like, 50 years, probably but I do like that as a process, because you’ll never predict the kind of result when you slow down the sensation of the space as well as the sound. If you were trying to do this in the box, you could bake in some reverb and delay, freeze that and then pitch it down, instead of just pitching down clean audio. You get some really haunting, interesting things going on with that simple process.”

What’s your typical approach to mixing? Is that something you leave to a separate stage or a natural part of the overall composition?

“I’ve mixed everything on my own up until now, but on this record I got help from a mixing engineer called Aneek Thapar. Just because it’s overwhelming to deal with so much material, it was important to get him along to help refine things after I’ve already put a lot of time into getting things close to where I want them to be. It helped to relax the mental process of dealing with the actual compositions, because I care more about the works than the sound sometimes. Obviously the sound is important, but if the sound is really amazing and I don’t care about the composition, then it’s over.”

You mentioned earlier about never venturing fully into the club world with your music. Have you ever considered writing a fully-fledged dance record?

“I’m not sure, really. I love techno and things like that, but I’m a sucker for structure. What I end up doing is taking elements from techno and using those with a more song-based structure. I’m not forcing it to be that way, but for some reason I just end up gravitating towards that. Could I make good techno? You have to have such discipline.

"There’s probably more Mogwai in my music than there is Tiesto"

“I've never thought of my music as being anything to do with dance music. It's got the physicality of dance music, but it's more shoegaze. There’s probably more Mogwai in my music than there is Tiesto. There's a headline! [laughs] It is kind of true; there's more of that world than the other world. At least it's probably 50/50.

“I'm a guitarist first, and whenever you do something first – let's say you learn guitar first, or drums first – you carry that prejudice into the future. And so a lot of my choices on the synth tend to probably sound almost like guitars, not on purpose, but because a certain kind of taste was formed. But with this record, I definitely tried to expand more, and the digital aspect was a way for me to do that.”

Rival Consoles' Landscape From Memory is out now on Erased Tapes.